Story and photos by Murray Schneider

Story and photos by Murray Schneider

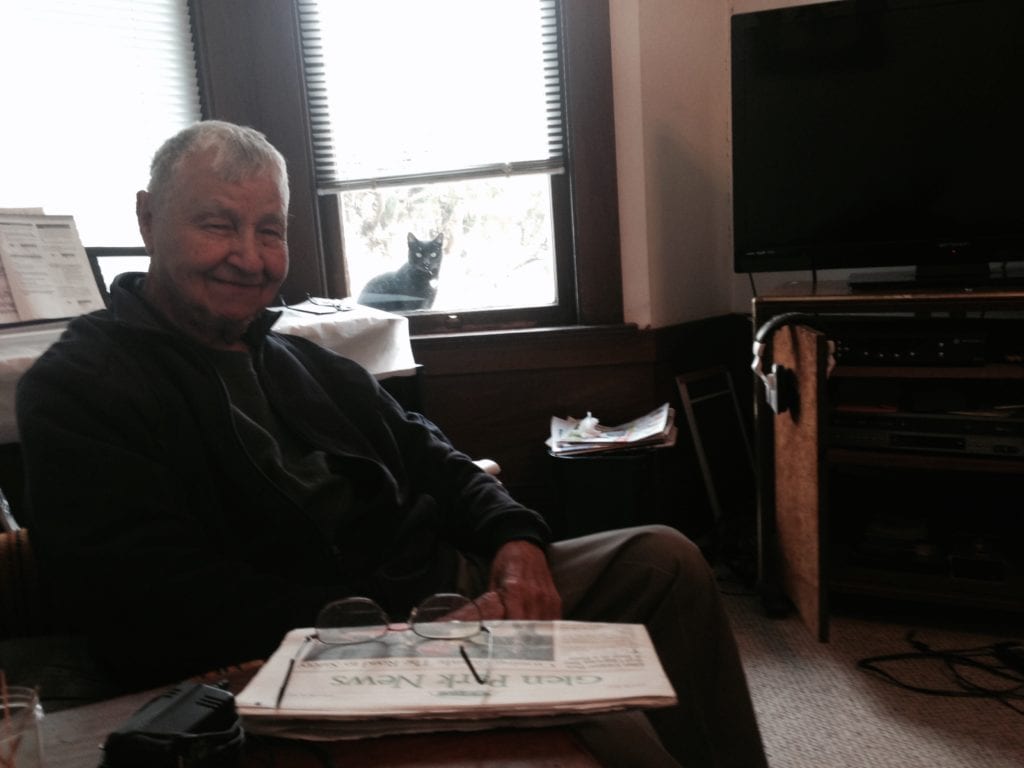

Last December, relaxing in his easy chair at 240 Chenery Street, Ernie smiled at Star, his 11-year old cat. Star’s face pressed against the living room window, her tail swishing at Ernie’s collection of front yard gewgaws.

Star wanted in, she wanted Ernie to open her window.

Ernie stayed seated in a home he’s lived in for 57 years. On the table next to him lay Star’s brush, a pair of reading glasses, a pencil jar, and a recent copy of the Glen Park News.

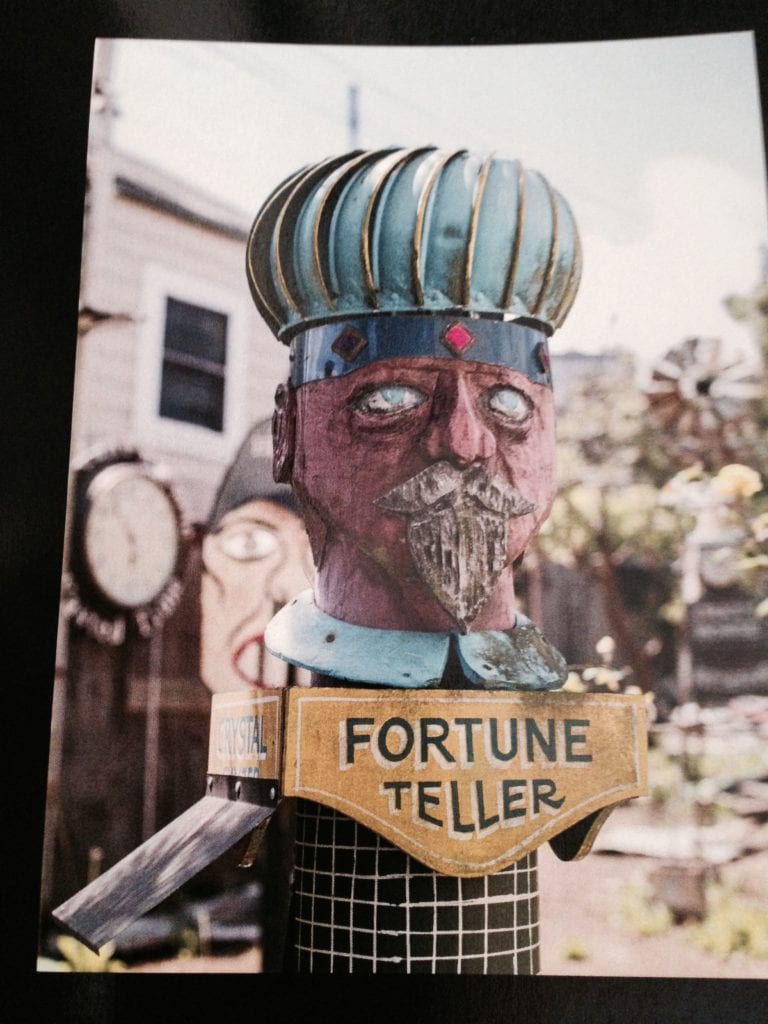

Ernie’s gewgaws, likenesses of Crazy Horse, a carnival fortuneteller, a slot machine, and an American prairie windmill stood outside behind Star. To the delight of Glen Park children there’s never been anything worthless about Ernie’s gewgaws, anymore than there had been anything useless about Laffin’ Sal, the Playland-at-the-Beach Fun House gewgaw from generations ago.

Ernie’s gewgaws, likenesses of Crazy Horse, a carnival fortuneteller, a slot machine, and an American prairie windmill stood outside behind Star. To the delight of Glen Park children there’s never been anything worthless about Ernie’s gewgaws, anymore than there had been anything useless about Laffin’ Sal, the Playland-at-the-Beach Fun House gewgaw from generations ago.

Laffin’ Sal guffawed; Ernie’s gewgaws don’t.

Ernie eased back in his armchair and felt like reminiscing. Star remained outside, as stoic as Crazy Horse.

“I painted the Fun House and a lot of the concessions at Playland,” he said.

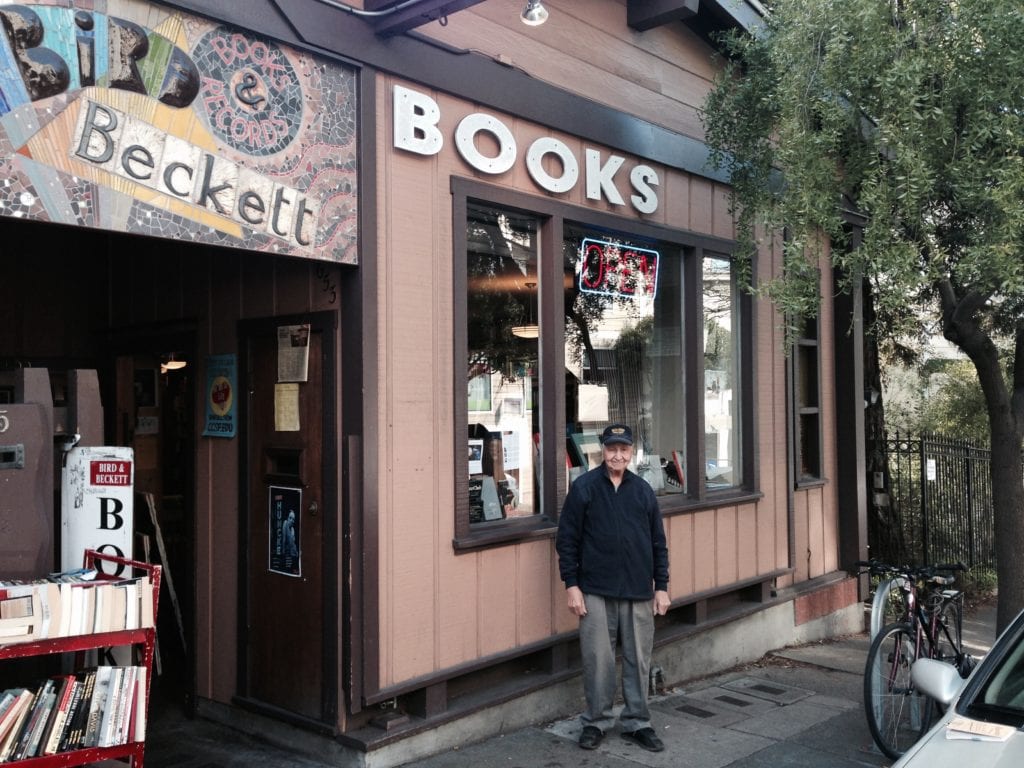

Ernie had painted lots of other things, as well. Such as signs and billboards, like the sign in front of Bird & Beckett that beckons one from Diamond Street to the Chenery Street bookstore. Bookseller Eric Whittington’s sign hangs like a pennant from the side of the building, and down the block a ways, above Hal and Susan Tauber’s hardware store, is still another sign Ernie had a hand in.

Ernie had painted lots of other things, as well. Such as signs and billboards, like the sign in front of Bird & Beckett that beckons one from Diamond Street to the Chenery Street bookstore. Bookseller Eric Whittington’s sign hangs like a pennant from the side of the building, and down the block a ways, above Hal and Susan Tauber’s hardware store, is still another sign Ernie had a hand in.

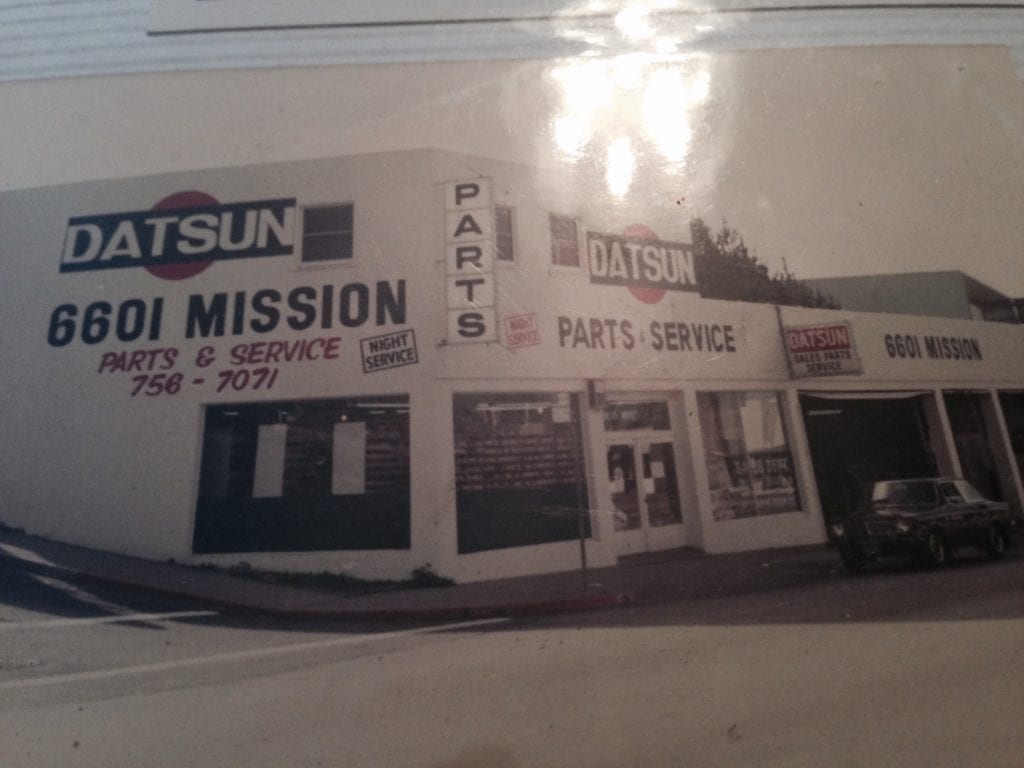

Ernie painted signs for over 40 years, only turning his attention to gewgaws when his day job ended. Once one could find his work on Metro parking lots directional signs, in City Hall and at SFO. Ernie began sign painting when Burma Shave highway signs were common, and Foster and Kleiser billboards skirted the skyline beside the Hamm’s Brewery within eyeshot of Seals Stadium at 16th and Bryant Streets. Ernie obtained his clients from the Yellow Pages and from referrals, and throughout his career he painted signs for Excelsior District pizza parlors, Sunset District dry cleaners and Mission District auto parts dealers.

“After work we’d go to Seals Stadium and get in through the right field gate when the seventh inning ended,” said Ernie, a mop of grey hair curling across his brow, an impish smile crossing his lips. “I named my daughter Brooks after Brooks Holder, a Seals outfielder.”

“After work we’d go to Seals Stadium and get in through the right field gate when the seventh inning ended,” said Ernie, a mop of grey hair curling across his brow, an impish smile crossing his lips. “I named my daughter Brooks after Brooks Holder, a Seals outfielder.”

Ernie Solon was born in 1926 in Allison, New Mexico.

“My father was an Apache, my mother was Hispanic,” he said. “My dad worked in the Madrid, New Mexico coal mines, and in 1943 when I was 17 I joined the Merchant Marines and saw the world.”

Sailing the seas, Ernie anchored in ports below the equator, dropping off cargo and collecting companionship.

“I liked the Central and South American ladies,” he said, his playful smile getting even wider.

“I liked the Central and South American ladies,” he said, his playful smile getting even wider.

Discharged on the West Coast in 1946, Ernie lived for a while in Contra Costa County, working for the Hercules Powder Company and the Pullman Company. Eventually he did a stint in the U.S. Army during the Korean War after being drafted.

At the end of the “conflict,” a civilian again, he ended up living in a Stockton and Union Street hotel in the early 1950s.

“It was a flop house,” he said. “So one day I’m sitting in a North Beach bar and there’s this guy next to me. His name is Jerry Salazar and we get-to-talking. Jerry’s a sign painter and he needed some cash. There’s not much to spend money on while shipping out and I’d saved some, so we did a deal. Jerry teaches me the sign painting business and I give him the money.”

Ernie stayed with Salazar until 1958 when he branched out on his own. He worked on Valencia Street and at Sanchez and Market Streets before bringing it all home to Glen Park where he set up shop at his own house.

That was a year after he met his wife.

“I met Betty in 1957 at a bar on Lombard Street. It was a time when neighborhood saloons had dancing, and I asked her for a dance,” he said. “Later, we’d go dancing at the Avalon in the City and the Ala Baba in Oakland.”

Betty and Ernie moved to Chenery Street and the children kept coming. Brooks, Frederica and then Domingo, who followed his father in the sign painting business for a while. Ernie and Betty schooled the kids at Fairmount Elementary, James Lick Junior High School and McAteer and Mission High School while Ernie wielded his brushes.

“Sign work wasn’t easy when San Francisco was a blue collar town,” said Ernie, “and the City was full of sign shops. We did our own lettering, and we needed heavy wood and 40-foot extension ladders. The secret was not getting hurt.”

“I’d take my ladders to Candlestick and do the sign work on the outfield fences,” he continued. “A decade earlier I did the signs for a Van Ness Oldsmobile dealership. Joe Perry sold cars there.”

The 49er fullback, once part of Kezar Stadium’s “Million-dollar backfield,” moonlighted selling a General Motors product when owning a Chevy, Pontiac, Buick or Caddy was a badge of one’s socio-economic status.

“I couldn’t drive an Olds,” said Ernie. “If you were a working class guy you couldn’t afford one.”

“Box stores and computers changed everything, though.”

“We worked hard, took our share of abuse from customers, but when the day was over we knew we’d created something that’d last for a dozen years, and we knew how to relax.”

Chenery Street wasn’t unfamiliar with Ernie and his buds hoisting a few brews, not simply ladders.

“When I came home, we’d have a few,” smiled Ernie. “It took me 10 years to learn the sign business, but I paid the bills and led a working man’s life.”

For that matter, his Glen Park neighbors weren’t unfamiliar with Ernie’s work regimen, either.

“I had a big account with the Triple A, painting AAA logos on its tow trucks,” Ernie said. “It was more work than I could handle, and there were often lines of trucks backed-up all the way to 30th Street.”

When the sign business slowed down, Ernie showed a streak of entrepreneurship and put Betty to work. There was a constellation of corner grocery stores dotting Chenery Street 60 years ago, and Ernie wasn’t afraid to add another at Randall Street’s corner. The shop opened in 1965, and Ernie lettered footprints to and from it for a block each way.

Ernie stood and walked to the window and opened it. Star inched through and jumped onto Ernie’s table, circling, waiting for him to return. Once he had, she brushed her whiskers along Ernie’s arm while he brushed his fingers across her black fur.

“Glen Park was like a tiny little Swiss village back then,” he said. “We had a Dachshund we called Burford, and we’d take him to Glen Canyon. Burford liked ice cream, so afterwards we’d drive him to Mitchell’s. Burford always liked slurping his ice cream from a cone. When he got hungry we’d pack him in the car and drive to Jack-in-the-Box on Mission Street across from Jefferson High School. The kids flipping burgers loved Burford. ”

All this was some time ago, a time when Diamond Heights builders emptied dump trucks of earth into Glen Canyon, and a dipped in chocolate double-decker ice cream cone cost thirty-five cents.

In 2014 at four o’clock in the morning a fire raged through Ernie’s Chenery Street garage, destroying a lifetime of brushes, equipment and tools.

But not his gewgaws.

They’re still in plain view as one walks by his house, and strollers still take time gawking at them.

“Crazy Horse is made from concrete,” said Ernie, about his replica of the Sioux warrior. “I added woodchips to give it texture.”

Behind Crazy Horse, who is in full war bonnet, is a windmill, which might have first seen service next to a Nebraska sod house, after passage of the 1862 Homestead Act.

“I ordered the windmill,” admitted Ernie.

Crazy Horse was shot dead while being held captive at Camp Robinson, Nebraska in 1877, and there’s only a small coincidence that Ernie’s daughter, Brooks, now lives in the cornhusker state.

A wizened fortune-teller stands next to Crazy Horse, and next to it is a casino slot machine with “Little Big Horn” inscribed on its face. Indian visages appear on three windows of the gambling machine: one says “Sitting Bull;” another says “7th Calvary.” The middle likeness is Ernie’s play on General George Armstrong Custer’s last name, a play-on-words, probably one of those words the FCC doesn’t allow broadcasters to use over the airwaves.

Ernie is 89 now. His Pacific Coast League Seals are long gone, packing up the same year he first unpacked his suitcases at his Glen Park house. His sign painter cronies are mostly gone, too, as is Burford. Mitchells is still selling ice cream, thankfully, only prices have gone up, and as for the San Francisco Giants replacing his beloved Seals, well, not enough can be said about them as far as Ernie’s concerned.

Ernie watches every game and now, just only a year from his 90th birthday, the working stiff who once handled a paintbrush with an expert hand is turning that same hand to learning computer software coding.

“I want to stay current,” said Ernie, who could have tutored Steve Jobs on the aesthetics of fonts.

Betty passed in 2013, and Ernie can’t help thinking of her when he looks as his gewgaws.

“You know how wives are,” he said, a twinkle in his eyes. “She’d look at Crazy Horse and the slot machine and say, ‘You want to fix something in the house, fix a door!’”

He stood and took a step or two from his chair. Star padded along, rubbing against his leg. Ernie fingered his stiff knees.

“Bad knees,” he volunteered. “Job related.”

By way of explanation, he said, smiling: “All that beer settles.”