Story and photos by Murray Schneider

Chuck Peterson, like Robert Zimmerman, was born in Duluth, Minnesota. Zimmerman went on to change his name, became Bob Dylan, and altered American music forever.

Chuck Peterson kept his name, moved to San Francisco when he was 20-years old and carved out a living as a working musician.

“I was a journeyman horn player,” said Peterson on a recent afternoon, sipping a cup of Higher Grounds coffee, sprinkled with three tablespoons of sugar. “I’d just show up.”

“I was a journeyman horn player,” said Peterson on a recent afternoon, sipping a cup of Higher Grounds coffee, sprinkled with three tablespoons of sugar. “I’d just show up.”

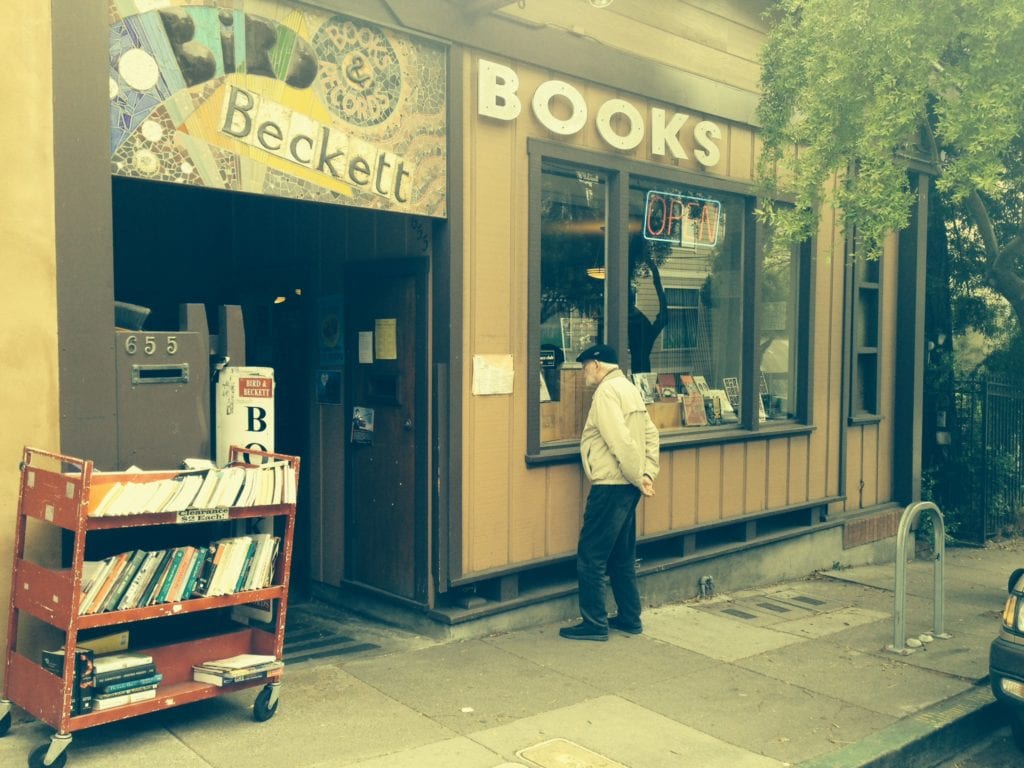

And he still does, continuing to blow his tenor saxophone on the fourth Friday of each month, as he’s done since 2002, at Glen Park’s independent bookstore, Bird & Beckett Books and Records.

Peterson didn’t begin with the intention of covering Charlie Parker on Chenery Street. “I wasn’t a jazz man. I just simply wanted to play music.”

Living both on Gennessee Street and Staples Avenue in the Sunnyside, Peterson eventually moved to Glen Park’s Martha Avenue in 1979, relocating recently to Arlington Street, directly around the corner from Eric Whittington’s bookstore.

Eighty-three years old now, he’s a bit challenged by steep hills and his eyesight is failing. “My partner of 35 years, Mary Cabot, helped me relocate,” Peterson said. “I’ve glaucoma, and it was hard carrying my sax up Martha Hill.”

Peterson had no trouble carrying his horn from Duluth, though, which he left at 14, moving to Eugene, Oregon where he completed high school and then enrolled in the University of Oregon. Leaving before he earned a degree, he came to the City in 1951, entered San Francisco State College and graduated with a BA in music. Subsequently, he gilded it with a MA in music and a California teaching credential.

Unable to find a full-time teaching job, Peterson began substitute teaching and playing music gigs at night and on weekends, and along the way he and his wife had three children. Principals’ secretaries called him to sub, but he coveted the calls from bandleaders and “contractors” from City hotels even more.

“They were called ‘casuals’,” said Peterson. “If I was lucky, I’d be called as a sideman at the Fairmont and the Mark Hopkins. It was the mid-1950s, and people wanted to dance to Glenn Miller.”

He landed a full-time job teaching middle school music in South San Francisco, a job that could have ended in a comfortable pension, had he remained, and he’d continued picking up music gigs while teaching Spruce Junior High School seventh and eight graders.

In his autobiography, bluegrass picker Ralph Stanley notes, “Finally my mother said, ‘I’m gonna’ get you a pig or I’m gonna’ get you a banjo.’”

Chuck Peterson had a similar dilemma; no oinkers in his San Francisco schema, just squealing middle-schoolers stealing time from him practicing his solos.

“I couldn’t play the music the way I wanted and do both,” Peterson said. “The last time I picked up a band leader’s baton was at a 1960 graduation ceremony. The superintendent was in the audience, and after “Pomp and Circumstance” he yelled, ‘You can come back anytime you want, Pete.’”

It turned out to be Peterson’s own commencement. There’d be no more daily lesson plans to write, no more homework to assign, no more quizzes to mark.

He turned his classroom keys in to his principal, and the only stage he ever walked across again belonged to the Curran, Geary, Golden Gate and Orpheum theaters.

“I just wanted to cobble together a living,” he said, hoping only his art could support his growing family. “In 1962 I got my big break. Tennessee Ernie Ford came to town, and I won an audition for his television show.”

Ford, who’d hit it big when “Sixteen Tons” topped the charts, put out a casting call, and Howie Dudune, Peterson’s San Francisco State classmate and his current band mate, wasn’t able to try out.

Musicians form a supportive Band of Brothers, covering each other’s backs as well as one another’s tunes. Dudune, an accomplished mainstream reed player, as well as a career middle school teacher, played at the time on KSFO Don Sherwood’s KTVU television show.

Dudune couldn’t audition, but his buddy could.

“I got the tenor sax chair, and I could also play clarinet,” said Peterson. “It was the best years of my life, both financially and professionally, and it led to other jobs.”

Tennessee Ernie Ford lasted from 1962-65 on KGO morning television. Two shows were taped a day, which allowed Peterson plenty of time to take on other night jobs and practice.

“For me it was always simple,” said Peterson. “Practice and be on time.”

From that point on, Chuck Peterson never looked back, his life for the next 37 years star studded, filled with a constellation of celebrities that could make a who’s who in the entertainment industry.

“I played in the pit orchestra at the Curran Theater when Carol Channing starred in “Hello Dolly” and the Golden Gate Theater when Rex Harrison played Henry Higgins in “My Fair Lady,” said Peterson. “I backed Yul Brynner in “The King and I”, and Mickey Rooney in “Sugar Babies.”

“Rooney would gab with the band,” he said, with no trace of being star struck, “but Brynner never came out of his dressing room.”

“The band played for “Mame,” “Hair,” and “Sweeney Todd,” he said, “but it was “Chorus Line” that was the most fun to perform because it had the hippest music. I played alto sax, clarinet, flute and piccolo. The more instruments you played the more you were paid.”

The role of starving artist was never far from Peterson’s mind, and he’d take whatever paying job came along, patching together a piecemeal living in pass through bands and one-nighters.

“I’d go into the recording studios in the Haight and on Bush and Folsom Streets and record jingles for 60-second commercials. Except for a Harrah’s commercial, there were so many I’ve forgotten now what was being advertised. I recorded “Spirit in the Sky,” and my daughter told me recently that it was used in a Denzel Washington movie.”

“In 1984 I took a sabbatical from “La Cage aux Folles” at the Orpheum and traveled to Japan with “The Wiz.” It was a New York band, but a local guy, Ron Stallings, played in it. Ron played with Glen Park Hardware’s Hal Tauber in their high school band.”

Eric Whittington is fond of pointing out that Glen Park is a Mecca for musicians. He’s not far off key when you think that Bobby McFerrin lived on Whitney Street and Stephen Shapiro still lives on Chenery Street.

“Rudy Salvini lived on Congo Street, and Howie and I played in his 17-piece band,” said Peterson. “We make it over to the Lake Merced Boat House for its Sunday dances.”

“And John Markham lived on Joost,” said Peterson, about his good friend who was married to Mary Goode, who, until her death, attended weekly Friday Night Jazz in the Bookstore. “John played in Rudy’s band and he’s gone now, too. John was a great drummer, playing with Billy May, Benny Goodman and Red Norvo.”

Peterson’s mantra, his familiar refrain, was “Have chart, will travel.” Hand him the music with his sax notes and he’d perform it; he’d never stopped working, blowing his horn at Pearls, the Chi Chi Club, the Palace Hotel, the Circle Star Theater and the Hilton Hotel.

“I even played the Moulin Rouge, a strip joint on Broadway,” Peterson winked. “The girls never talked to us guys in the band, though.”

“But the best jobs were always the theater ones because between matinees and the 8 o’clock show there were three hours to kill,” he said “I loved to hang out in bookstores.”

There was Stacey’s on Market Street, the Holmes Bookstore on Third Street and plenty of stores in Union Square before Amazon ran them out of town, and he’d hit them all between performances.

“When Eric took the newspapers off the windows from his original Diamond Street store, and a sign announced Bird & Beckett it caught your eye.” said Peterson. “I’d asked Eric’s predecessor if she stocked Elmore Leonard and she asked ‘who?’”

“Now, here was a bookstore that boasted ‘Bird’ for Charlie Parker,” said Peterson, whose literary tastes transcend genre mysteries and include Philip Roth, Bernard Malamud and John Updike. “If I didn’t have a book in my hands I’d go nuts.”

What he also had in his hands now was the income to support his family, because as a member of the American Federation of Musicians, Local 6, he earned a living wage and enjoyed full medical benefits.

“During this time there was something called Music Performance Trust Fund that filtered residuals from the recording industry to the national union and it trickled down to Local 6,” said Peterson. “In the mid-Sixties some of us formed the Sideman’s Association to ensure that where the money ended up was day lighted. Today you’d call it transparency.”

“In this way, we were able to finance something the City called “Music in Public Places,” which showcased acts in Aquatic Park and Golden Gate Park. The money didn’t come directly to artists, but it meant additional jobs for us and benefited the public at the same time.”

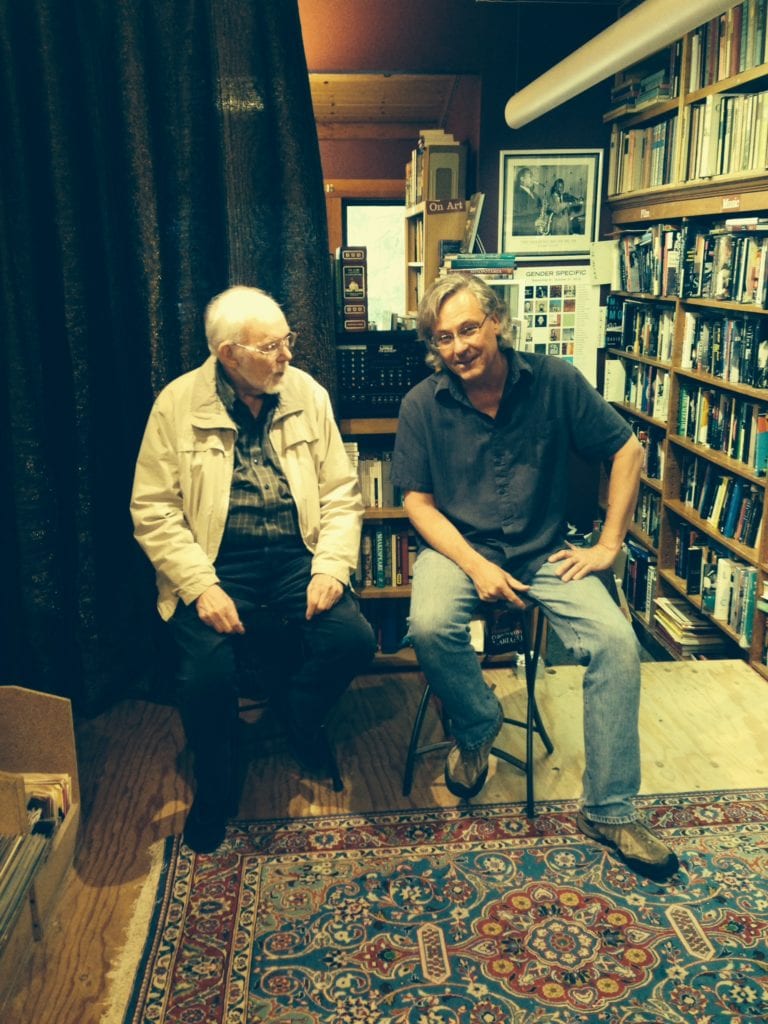

Eric Whittington adds, “Chuck wasn’t afraid to push for better contract terms for working musicians and, in fact, from what I’ve heard, he was at the forefront of winning certain contract concessions that helped keep the profession viable in the late 1950s, 60s and 70s.”

“Musicians today joining together into collectives might be a contemporary way of helping raise everyone’s standards and earning capacity,” said Whittington. “The main thing is to collaborate and support each other.”

While the jazz idiom will never be confused with that other American musical genre, Ricky Skaggs puts his own spin on matters when he writes about the father of bluegrass: “If Bill Monroe hadn’t come on the scene, where would Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs have been. You can see from that trunk how much fruit came off the Bill Monroe sprout on the tree.”

“Chuck’s the founder,” said Whittington, recognizing Chuck Peterson’s legacy. “Chuck gave us the opportunity to get this thing started, and he and his confreres are still at its center, and the young players will make sure it doesn’t stop.”

If so, you need look no further than Whittington’s Friday night jazz repertory. Jimmy Ryan, Don Prell and Scott Foster all sprang from Peterson’s trunk 14 years ago when Whittington first shelved copies of “Be Cool,” “Out of Sight,” and “Riding the Rap.” All continue performing today, fronting their own ensembles, influencing their own disciples while entertaining Glen Park audiences.

“Chuck and his colleagues bring decades of priceless experience to the Bird & Beckett bandstand and embody a direct link to bebop’s formative years,” emphasized Whittington,” again speaking to Peterson’s seminal influence as a bridge between past, present and the future.

“As it turns out,” Whittington added, “for young players bop continues to provide a wealth of musical raw material and ways of interaction in performance, so that music has the potential of being always fresh and inventive.”

“The trick is to provide our musicians with good venues and appreciative, informed audiences so that being a professional jazz player in San Francisco is a viable way to make a living,” said Whittington. “The bookstore’s music series is our way way of offering support to the musicians, ensuring that the cultural legacy they safeguard isn’t squandered and lost.”

Like the jazz he ended up performing, Peterson’s professional life after he left the classroom was nothing if not improvisational, made up as it went along.

“Jazz,” he said, “is not scripted, it’s full of self-expression and variations.”

“I was a less than top-of-the-line saxophone player,” said Peterson, “but it was worth it because I always worked.”

Whittington begs to differ. “Chuck is a thoughtful and soulful player, who swings hard and blows with conviction.”

Along the way, he backed Petula Clark, played at Bimbos for a year-and-a-half, and played behind Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis, Jr. and Marvin Gaye.

“I made an adequate income and I enjoyed doing it. It was always changing and it was never dull,” he said, “and now it’s a pleasure to continue playing before for the knowledgeable audiences at Bird & Beckett who sit, listen and never talk.”

Oh, then there’s Elvis.

One can’t mention Chuck Peterson and not bring up the “King.” Elvis may have left the building, but not before he encountered Glen Park’s rhythmic favorite son.

“We went on a four-city tour with Presley, to Oakland, Portland, Seattle and back to the Cow Palace,” said Peterson. “As jazz players none of us knew much about him except his name.”

“We weren’t allowed to have any contact with him,” said Peterson, “even in the hotel. Security was tight.”

Eric Whittington likes to think music is local, housed in venues such as his where neighbors can come together and share a culture of sound, uncork a bottle or two of wine and exchange the views-of-the-day during set breaks.

Maybe even buy three or four books, certainly one or two. From such camaraderie community is fashioned Whittington is convinced.

Possibly the last word on Chuck Peterson, then, should go to one of Whittington’s own neighbors, Hal Tauber, who played saxophone in the George Washington High School band and who walks up Chenery Street after he closes his hardware store on Friday nights and often stops in and listens to Chuck Peterson.

Tauber nailed it, brooking none of Peterson’s patented self-deprecating modesty, providing the last word on Peterson’s lasting legacy.

“He’s a wonderful sax player. I mean good. Really good.”

If you’d like to see for yourself exactly how good, how really good Chuck Peterson plays, you can see Peterson and his quintet play at Bird & Beckett on the fourth Friday of each month.