San Francisco is constantly reinventing itself. Gold Rush seekers giving way to Comstock silver barons. Merchantman brigs surrendering to coal powered steamships, then complemented by coal-powered railroads. The latter engineered by entrepreneurs with names such as Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins and Crocker.

Which got me thinking about how, less than a century later, the outer Sunset District where I grew up, morphed from sand dunes to modest housing for post-World War II families such as mine.

Got me thinking, too, about the early immigrants who’d transformed San Francisco. Take Adolph Sutro. He comes to mind because in Glen Canyon Park you can easily see a stand of eucalyptus trees he established across Islais Creek. The trees dot the canyon’s western slope.

Sutro was born in 1830 to Jewish parents in what today is the North Rhine-Westphalia and in 1869 made both his reputation and fortune engineering what became known as the Sutro Tunnel. His hydraulics and ventilation facilitated the drainage of water and then the removal of silver from flooded Nevada mine shafts. He believed the Australian gum tree could act as windbreaks and for use as railroad ties. The windbreaks worked along the western frontier of San Francisco; the gum trees didn’t: their leaching oils made for imperfect wood.

The Sutro Baths

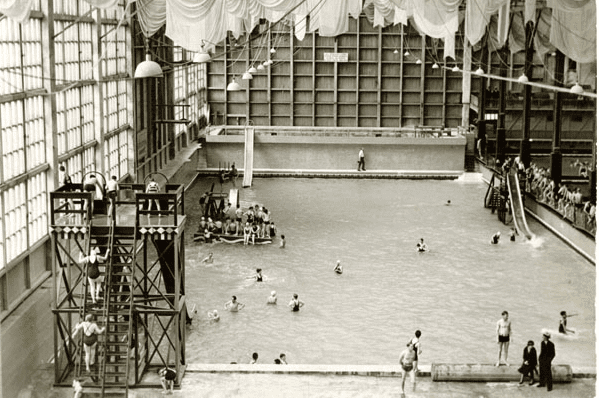

What did work, though, were his Baths. Sutro served as the City’s 24th mayor for two years beginning in 1895. He thought of his seven pools, built in 1896, as “health giving amusements that would equip working men and women for the struggles of life.” Situated north of the Cliff House, which Sutro owned, the two-and-a-half acre aquatic spa stood in the lee of the Point Lobos headlands at Seal Rock Cove.

I swam for the first time in 1953, when I was ten-years-old.

The six concrete salt-water pools and one spring-water cement tank were only a bicycle ride from my Outside Lands home at Lawton Street and 32nd Avenue.

Once at the Baths, I’d fish 25 cents from my jeans and enter the airy building. It was an engineering feat that boasted hundreds of panes of glass and pumped in millions of gallons of seawater. I’d descend three stories to enter the locker room. Before exiting the changing room I’d grab a brass locker tag that I’d either safety pin to my trunks or wrap around my neck. I’d earlier been handed two towels and a wool bathing suit that itched and became so water-logged with ocean water that after an initial foray into the briny water that I’d sink to my neck.

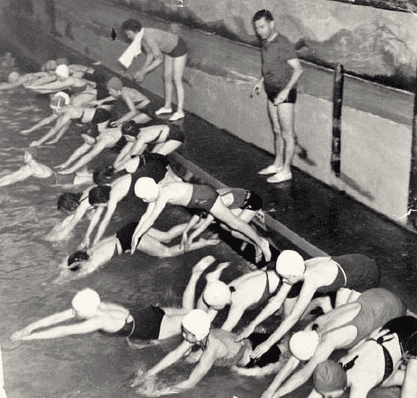

I learned to swim at the Jewish Community Center on California Street and weathered Fleishhacker Pool, a public salt-water swimming pool next to the San Francisco Zoo built in 1925. It was one of the largest heated outdoor swimming pools in the world and remained open until 1971.

But it’s Sutro’s glass enclosed entertainment palace — his munificent gift to the City’s working class families — that I returned to time after time.

A first taste of history

But it wasn’t the pools that lured me with their diving boards, flying rings and slides, nor the P.T. Barnum side show-like museum that boasted exotic oddities such as Egyptian mummies, Polynesians spears, and an Amazonian 18-foot anaconda wrapped around a rainforest tree.

Nor was it the midway promenades, tropical plants, stuffed apes, bears, jaguars, or what today would be dubbed the politically incorrect cigar store Indian that stood stoically at attention.

As I stepped down the grand staircase to the second level, on my right were photographs of long gone men and women who, when they lived 60 years earlier knew only that it was not their past being recorded but their ongoing present. Most striking of all, though, was their clothing, which seemed no different than the ones worn by my four grandparents, whom I’d never met, but who were pictured in studio portraits on my parents’ bedroom dressers and night stands.

The Sutro Baths were a Victorian epiphany, burnished by dozens of descents along the Comstock Lode engineer’s edifying stairway. He had photographically advertised his wish to “educate and stimulate. ” His photos certainly did, the equal to if not better than did my Lawton Elementary School’s fourth, fifth and sixth grade teachers Mrs. Crabtree, Miss Twomey and Mrs. Burdick.

Dwelling upon those photographs, photos of Gilded Age women delicately lifting their hems to avoid lapping water and of men comically juggling picnic baskets and blankets, is when I first caught, then nurtured, a lifetime love of history.

John Martini, who served as a Golden Gate National Recreation Area park ranger from 1974-99 and is author of “Sutro’s Glass Palace,” recently told me these photographs were taken by William Billington and Martin Behrman and are available for research at the Main Library. Their historic significance was beyond me then, but a decade later, in 1963, my San Francisco State College history professors schooled me as to what each photo really meant, which I’d unwittingly intuited.

Each photo, they taught, represented “continuity,” one half of an equation that braids together all historical analysis.

A city not immune to prejudice

And later? What about my own classroom? I’d have liked to have entertained my students with stories of how I’d dog paddled with kids from the Fillmore and Chinatown when segregation was the norm at public swimming pools throughout the United States. I would have delighted in spinning tales of how I’d not simply been an observer of historic “change,” the other half of any historical analysis, but how I’d been a participant in it. Paraphrasing novelist Thomas Flanagan, I would have liked to “have tricked them into knowledge with the honey of anecdote,” but one year before Brown v Topeka Board of Education I simply don’t recall the racial or ethnic compositions of the Baths.

I do remember, though, there were all those pools, some heated at different temperatures, and I recall hearing stories of how heartier swimmers than I would jump into a frigid one and then immediately leap into a warmer pool.

Martini has surveyed troves of photographs dealing with the Baths and he added perspective.

“I have never seen a photo taken of minorities [at the Baths] before 1950,” he told me.

Martini, however, has unearthed one photo, taken in 1952, that shows African-Americans in one of the Sutro’s pools.

San Francisco, always a work-in-progress, has a way of transforming itself. A dozen years before Sam Cooke sang, “It’s been a long time, a long time coming, but I know a change is gonna come,” it appears, thanks to John Martini, that San Francisco embarked upon a seismic shift.

I’ve never stopped swimming, sometimes as often as five times a week. At YMCA pools on the Embarcadero or in the Presidio. I’ve jumped in public pools such as Sava and Rossi, even challenged the length of the University of San Francisco’s Koret pool.

A new pool for Balboa

So it was a no brainer when the Balboa Pool reopened and Fernando Aguilar, a PG&E project manager and School of the Arts beekeeper, suggested we give it a go. Aguilar, a football and baseball letterman at McAteer High School, has made it his mission to swim in each one of Recreation and Park’s nine pools.

Balboa Pool is a downhill walk from my house, which sits atop O’Shaughnessy Hollow in the shadow of Mount Davidson. The hollow is named for another civil engineer, Michael O’Shaughnessy, an Irish immigrant responsible for Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Dam.

In Adolph Sutro’s time, Mount Davidson was called “Blue Mountain,” undoubtedly because its slopes were tangled with huckleberry and elderberry. At over 900 feet, it’s the highest spot in San Francisco, a mixture of Natural Resource Division-stewarded grassland and Sutro’s gum trees that first outcompeted then overwhelmed the mountain’s bounty of berries.

It took two years and four months and $9 million to put the Balboa Pool to rights, a victim of rotted windows and a faulty electric system. The wait — it reopened in February of 2019 — was worth it.

Expansive new glass windows are now in place, not as many as Sutro installed in his swim palace, but ones that look out over a Mission Terrace panorama and beyond to well-kept neighborhood houses. Now ADA accessible, the six-lane 25-meter lap pool has a movable divider, providing Recreation and Park Department swim instructors flexibility in offering swimming lessons.

At poolside stand two bleachers, each with three sets of bench rows that look over a pool that is eight-feet at the deep end and four-and-a-half in the shallow end.

Formerly utilizing deck-side showers, the facility now boasts men’s and women’s locker rooms with three showers and bring-your-own-lock lockers.

Suna Mullins lives on Flood Avenue, four blocks from the pool. Brought up in the Sunnyside house where she and her husband now raise their two children, she’s been swimming at Balboa her entire life,

“I swam there as a child and it was spacious,” emailed Mullins, who moved to Flood Avenue from Chenery Street when she was six months old. “The lifeguards were kind and the building felt like a cement box. To enter and exit the pool there were a number of showers spraying in all directions that got you on your way back and forth from the dressing room. I appreciate a separate section now in the women’s dressing room, and I love the spacious windows that allow swimmers to look onto a green field.”

The day Aguilar and I showed up, a couple of days after the pool had reopened, we paid $6. Unlike the Sutro Baths, I bought my own swimsuit and my own towel. A lock, too. When I revisited the pool on July 14, I found the entry fee had jumped to $7 a swim. Best of all, though, I can take advantage of senior swim at a senior rate.

Gracing the wall opposite the locker rooms is a colorful 13-foot-by-37 foot mural, courtesy of a City art fund. Painted by Jason Jagel, it depicts swimmers representing Glen Park and the Sunnyside and adjoining neighborhoods.

When Aguilar and I entered the shallow end we had the entire pool to ourselves. We each took a lane. While we adjusted our goggles, a woman joined us. Aguilar knew her from a previous outing at another City pool. She staked out her own lane. Each of us kicked off. I swam ten laps, rested, then another ten, rested again and then a final twelve. The water was warmer than Sutro’s and chlorine substituted for salt, and by the time we climbed the ladder each lane was occupied.

A blue-collar oasis

Ten years before the Progressive Movement, Adolph Sutro ushered in a moment-in-time that provided blue-collar San Franciscans wholesome recreational activity. The Sutro Baths were a bit of a white elephant. Housed at the farthest reaches of San Francisco, the pools found it difficult to make money, rarely tuning a profit.

They endured micro-transformations along their 60-year gestation. To attract more users, in 1937 Sutro’s heirs closed two pools in favor of new volleyball and basketball courts. Eventually another pool was drained and converted to an ice skating rink.

In October 1952, the aquatic palace that had survived the 1906 earthquake was sold by Sutro’s grandson to George Whitney, owner of Playland-by-the-Beach. Whitney attempted to shore it up with curiosities such as Tom Thumb-circus-look-alikes.

By 1953, after I took my first plunge, the handwriting was on the multitude of palace windowpanes. The pools were destined for shuttering, finally succumbing in 1954. While ice-skating continued, carnie trucks spent the next several years hauling away memorabilia that would have been the envy of Barnum and Bailey or the subject of Ripley’s “Believe it or Not.” Sutro’s two Egyptian mummies even found their way to San Francisco State College where I earned two history degrees and a teaching credential.

A providential fire

The Whitney family schemed to unload the land to the same developer who’d afflicted Aquatic Park with the Fontana apartment buildings (think Soviet-era architecture). Before such a catastrophic real estate blemish could besmirch the Pacific Ocean view, in June 1966, a mysterious fire razed Sutro’s glass beneficence. The land it sits on today was secured in 1980 as part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

While Adolph Sutro’s largess is gone, his legacy can’t go unnoticed for long. The Sutro Tower is visible from almost any place in the City. One can visit the Sutro Library at San Francisco State University and walk through his Sutro Forest behind the University of California at San Francisco.

From where John Martini led his tours, only feet from the Golden Gate National Recreation Center Visitor Center, one can see the pools remnants below. There’s even an outdoor staircase that leads to what remains of the concrete pools.

“Don’t ruin the ruins,” John Martini told me is a phrase he’s used since the 1970s.

“I’d paraphrase visitors who voiced fears at public meetings,” Martini telephoned me, “that any rehabilitation efforts would ruin the ambience of the site.”

The Balboa Pool, which first opened in the mid-Fifties, isn’t gone; it’s been rehabilitated to the delight of San Francisco-born Suna Mullins and her children, Leyla and Patrick.

“It’s such a great improvement,” Mullins emailed.

On February 23, District 11 supervisor Ahsha Safai stated, “Balboa Pool is the final piece of the major renovation we have led for Balboa Park in the last decade. It will be the crown jewel of pools for generations of San Franciscans for years to come.”

Photo: Suna Mullins.

Other changes

Leyla Mullins is eight years old and Patrick Mullins is six years old. Since the pool has reopened the siblings have been back nearly a half a dozen times. Like their mother did at their age, they swim.

Suna Mullins and I recently sat at Higher Grounds. I sat across from her, sipping a cup of coffee, thinking about my own mother who on those long gone San Francisco summer days would shoo me off to the Sutro’s Baths. She’d ensure that I tucked a house key and some coins in my Levi’s and carried a lunch pail on my Schwinn handlebars.

Then I’d peddle off. I can still hear her reminding me.

“Be home by dinner.”

I asked Suna Mullins if her kids bicycled by themselves to the Balboa Pool. It was only four blocks, after all.

Suna looked at me for a long moment, then smiled.

What she replied tells yet another tale of how San Francisco has transformed itself in the last half century and counting.