Chef Sharon Ardiana standing next to a photo of her grandparents, William and Gialina Ardiana.

If you’ve eaten at Gialina’s, you’ve had dinner with them. But do you know who they are?

The they here, of course, are the people in the amazing black and white photos that grace the walls of Gialina’s, the Glen Park restaurant on Kern Alley.

Since it opened 2007, diners have pondered those photos as they ate to-die-for pizza and roasts.

On a recent afternoon chef and owner Sharon Ardiana’s door stood propped open. Wearing a white apron over a black T-shirt, she prepped behind a counter where she could easily look out at the quartet of photos.

The one closest pictured her in 1965, at age seven. She poses with her grandmother, Gialina Ardiana, and her dachshund, Max. Ardiana is kneeling, her hands circling Max’s neck. Next to her, Gialina wears a dress that looks as if it were in the height of fashion a decade or two earlier. Looking at the photo, it’s easy to see the woman the girl will grow into.

The photo was taken at the Ardiana home, a few miles from Pittsburgh, where she lived across the street from her grandparents. The house is perched on a hill, surrounded by shrubbery, and the neighboring homes appear to descend into a valley where a steel bridge crosses a river. It’s Monongahela River country, the region in western Pennsylvania famous for the two Joes (Namath and Montana), steel and coal.

“The photograph reminds me of my connection to Nonnie and childhood fun,” said Ardiana. She busied herself slicing summer squash, which only hours later would top her crusty white corn pie.

Fun for Sharon Ardiana means food. And food has always signaled both her grandmother, whom she named her artisanal pizza restaurant after, and her mother, Rose Marie.

“We had Victory gardens long after the war,” Ardiana said. “My dad poured over the Burpee gardening catalog, and we’d grow tomatoes, peppers, walnuts, pears, peaches Italian plums, raspberries and strawberries.”

“Before that, during the Depression, everyone was poor,” she added. She continued corralling squash while an employee pummeled pizza dough behind her. “We had chickens, but they weren’t pets.”

“In 1910, my grandparents came from Reggio Emilla, which is in the center of Italy,” she said. “They wanted to assimilate as soon as they could.”

She moved to the second photo, which depicted a 1956 meal, the sort of Sunday family dinner that looks ever so American, ever so familiar. Ten people sit around a bountiful table. Gialina sits at the foot of the table, a wine bottle held at familial attention in her right hand. Next to her sits her daughter, Rose Marie, Ardiana’s mother. Gialina’s husband, Ardiana’s grandfather, William, sits at the head of the table, bent over the main course. At the other end of the table is Sharon’s ten-year old sister, Pat.

But it’s the man next to Pat who captures your eye, grabs your attention. Raymond Ardiana, Gialina’s son and Sharon’s father, was 41 years old when the photo was taken. He looks healthy, vigorous and toughened from forging steel in a Pittsburgh’s mill. He looks like he could be the backstop for the perennial cellar dwelling Fifties Pirates, his hometown starting nine. He wears one of those patterned short sleeve sport shirts so popular during the Eisenhower years. His black hair is freshly clipped, as if he’d just returned from the barber where he’d traded tall tales about the Bucs’ Roberto Clemente and the right fielder’s rifle arm.

He is everyman, every child’s blue collar father, the father who took neighborhood kids in the winter to the park to go sledding, the father who built a bonfire to keep everyone warm and safe, the father who stayed and watched over everyone, and who in the summer organized wiffle ball games for the same gang of children with names such as Slugo, Betty, Chubby and Lulu.

“My dad came home from the Mesta Machine Company steel mill at 4 o’clock each afternoon,” Sharon Ardiana reminisced. “He’d take me to pick watercress. He’d hunt, too. We had beagles. And my mom? Well, she’s still a great baker and she’d cook every day. My love of food came from them both.”

“I wanted this to be where people make the connection between food and family,” she continued. “I wanted this place to be a restaurant where people want to come – kids, gay, straight – a great neighborhood place.”

One wondered if any of her childhood cuisine translated to her restaurant, which the San Francisco Chronicle awarded one of the “Best 100 San Francisco Restaurants” for five consecutive years beginning in 2009.

“Not really, nothing specific,” said Ardiana, “It’s about memories, though. My family cultivated me by letting me experience what lettuce tasted like coming from the ground.”

“My mom would have me taste stuff. I was a taster,” she smiled. “My mom would say, ‘don’t eat it if you don’t like it, but taste it!’”

Ardiana had ample opportunity to do the sampling along the way to San Francisco, where she landed in 1989.

She earned a bachelor’s degree from Penn State and intended to teach middle school, but instead attended the Restaurant School in Philadelphia. She began cooking professionally in 1982, and once established in the city she apprenticed at Boulevard, Slow Club and Gordon Biersch.

“Friends opened Chenery Park and I discovered Glen Park,” she said, recounting her epiphany. “It’s like a village here, charming and real, and different than any other place in the city, and that’s why I put my business here.”

Ardiana opened Gialina in January 2007, staffing it with 16 people, three of whom build and cook her pies, prepare salads and deserts and four others who are full time servers. Piggybacking on her success, she opened Ragazza on Divisadero Street several years ago that offers much the same fare, but to a much different demographic, and which also quickly became recognized as another “Best 100 San Francisco Restaurants” in 2012 and 2013.

“It’s more like date night,” she said of her NoPa bistro, which caters to the hipster-chic habitués of Hayes Valley and the Lower Haight.

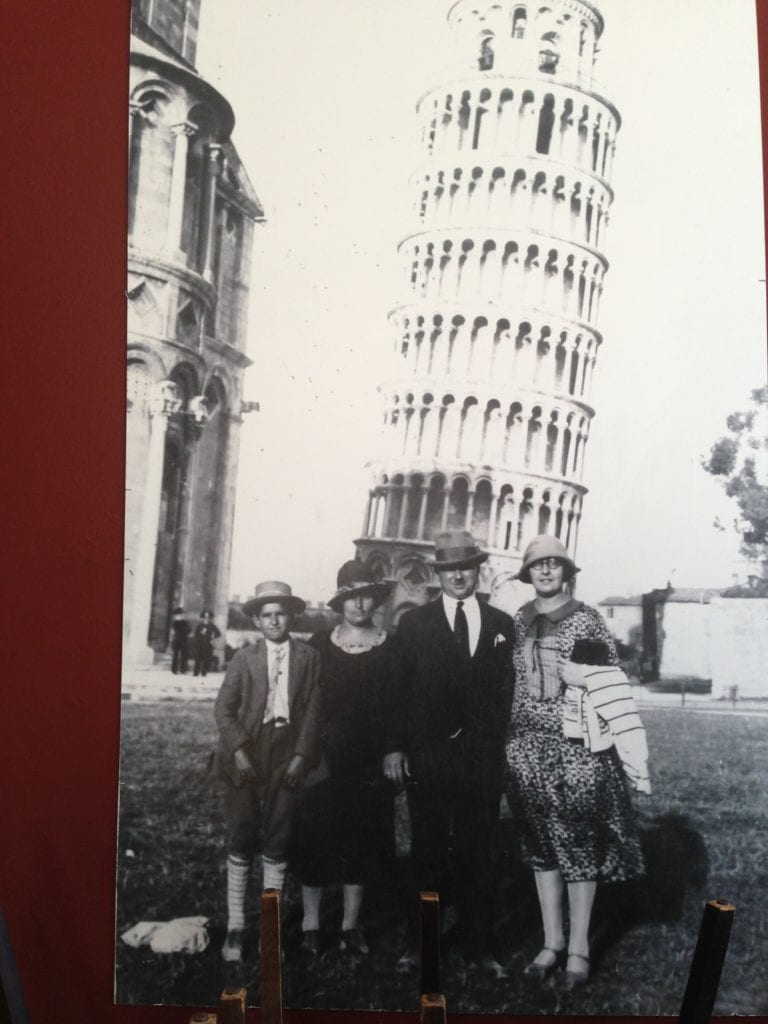

Her door remained ajar, the sun streaming through, making the space even toastier. She angled toward the photo taken in 1926 in front of the Leaning Tower of Pisa when her family returned to visit Italy, traveling by steam ship one year before trans-Atlantic airplane flight. Her father, then eleven, stands beside his mother. They’re shoulder-to-shoulder with companions whom Ardiana can’t identify. The quartet looks like tourists, dressed in their Sunday finest bought with the living wages William Ardiana earned in the thriving domestic steel industry.

“I always liked history, particularly Italy’s,” Ardiana said. “As a child I was fascinated by these photos and I loved looking at them. My great uncle was an amateur photographer, and he took them all, except for the Leaning Tower.”

“They’re an extension of me,” she continued. “They make association with my family, they’re historical and they’re funny.”

A glance at the remaining photo verified this.

Ardiana’s grandparents sit on a family sofa. It’s Gialina’s birthday. Both recline, familiar with one another after a lifetime of marriage. Gialina holds William’s hand. They’re both stouter now. She’s comfortable in the sort of dress she seems to have favored over a lifetime; he’s girdled in a pair of high-wasted pants that sabotaged men of that era. He’s buttoned up, but a sliver of a smile escapes his lips.

But it’s the birthday headgear each favors that lends the scene its anomalous and comedic air. William dons a petit party-favor hat; Gialina boasts a full-blown smile, her eyes sparkle, and her hair is set off with a festive bow.

“This is the funny one,” said Ardiana, “because my grandparents weren’t a laugh-a-minute people.”

While Ardiana was young, Gialina suffered a stroke, which inhibited her speech.

“She couldn’t communicate all that easily and she never wrote anything down, but she was a force,” said Ardiana, “and she showed me things like which seeds to plant and which opera books to read.”

“She’d take me to the backyard and demonstrate how to prune and how to shell beans,” she added. “One day a bird came into the house and she went into an elaborate pantomime about how it flew from room-to-room.”

Gialina and William are both gone. So is Raymond Ardiana who died young at 54 in 1969, two years year before his long-suffering Pittsburgh Pirates snagged a second World Championship in eleven years. Rose Marie, Ardiana’s mother is still going strong. Pat, Ardiana’s sister, works for the United Jewish Federation and lives close to her mother who still manages quality kitchen time.

“I wanted to honor my family,” said Ardiana, surveying her restaurant, still empty but soon to be packed with hungry foodies, many prepared to spill onto Diamond Street and patiently stand or wait on two wooden benches for coveted seating.

“The neighborhood accepted me and embraced me,” she said. “Gialina is my way of thanking it for being here, thanking you all for coming.”

Stopping to take a breath, she added. “If I built it they would come. It’s my Field of Dreams.”

Forbes Field aside, of course.