By Murray Schneider

In 1926 Chris Mickelsen built a two-bedroom house at 201 Joost Avenue. Afterwards he decided he didn’t want to stop with a bungalow that straddled the uphill side of Baden Street, so he went on to construct a good portion of western San Francisco, including homes surrounding Stonestown. Still not done, he crossed the county border into San Mateo after World War II and, as construction superintendent for Stoneson Brothers, helped build Broadmoor Village in Daly City.

“My father was an earlier riser,” reminisced Ron Mickelsen, Chris’s son, now 80, who was raised in the Joost Avenue house. “He believed America was all about opportunity and he was willing to work hard to get it.”

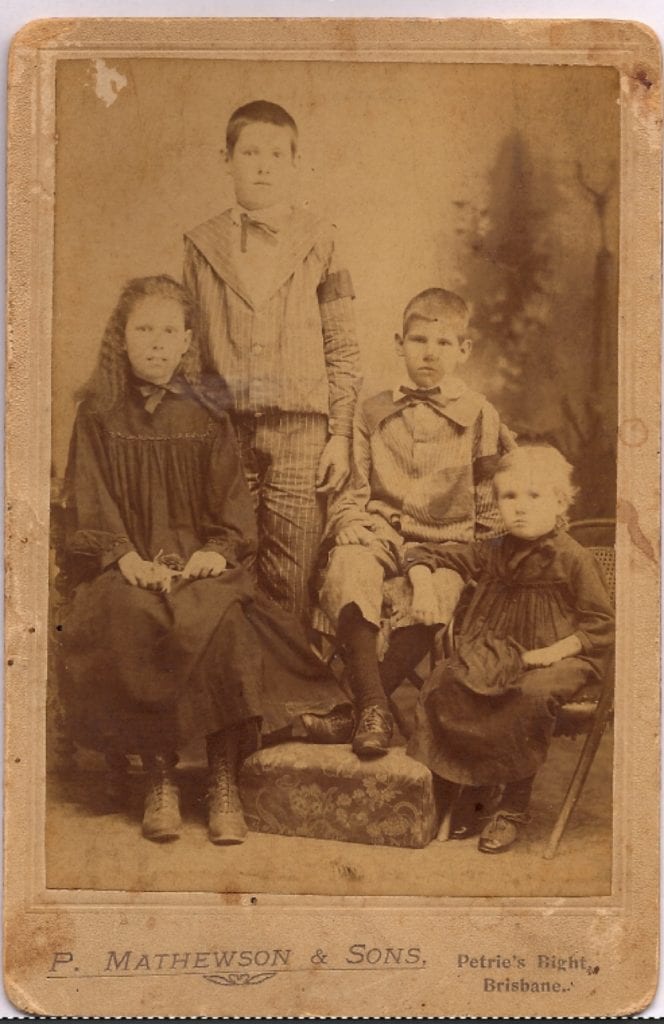

Chris Mickelsen was born in Aarhus, Denmark in 1893 and followed his parents, Hans and Laurine Mickelsen, to Whitehorse, Wyoming where Hans mined the coal that fueled the Union Pacific Railroad. An immigrant experience oft repeated, the Mickelsen family odyssey didn’t end on the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains.

“My grandfather was an accomplished bricklayer,” said Ron Mickelsen, who attended Glen Park Elementary, then James Denman Junior High School and eventually graduated from Balboa High School in 1950. “After the 1906 earthquake and fire, he and my grandmother came to San Francisco and helped rebuild it.”

The Mickelsens moved into their home at 511 Congo Street, a house now on the Google route between Monterey and O’Shaughnessy Boulevards. Back then it perched on a windswept slope that included neighbor’s chickens and goats and eucalyptus trees that dotted the incline. From the hill Hans went on to repair brickwork destroyed by the quake and Chris perfected his journeyman carpentry skills while continuing to pour over the Sears Roebuck catalog, practicing his English.

World War I broke out and Chris put down his carpentry tools and picked up a Fort Lewis, Washington basic training rifle, drilling as a member of the fabled all San Francisco 91st Division.

“Joining the army was the fastest way to citizenship,” said Ron Mickelsen. “My father always said Denmark didn’t do a darn thing for him and he wanted to become an American as fast as he could.”

Before being shipped to France and the Western Front, Chris met Anna Cramer, a Bellingham beauty, and after the 1919 Armistice the doughboy found his way back to the Puget Sound, married her in 1920 and returned to San Francisco where the newlyweds took up residence at 34 Nordhoff Street, a one bedroom, 560 square foot house around the corner from Chris’ parent’s Congo Street house.

It was in this earthquake “cottage” where their first daughter Evelyn was born in 1921, soon followed by Lorraine in 1923. The Nordhoff Street house quickly became too small, so Chris, when he wasn’t busy swinging a hammer at starter homes in and around Lakeside Village and the Parkside, turned his hand at building 201 Joost Street for the princely sum of $1,000!

Chris and Anna moved there in 1927 and Ron Mickelsen was born there in 1932.

Ron Mickelsen’s boyhood was unlike the challenging Wyoming one experienced by his father. If anything, Ron’s Sunnyside arcadia resembled more a fictional Huckleberry Finn idyll, which substituted Islais Creek for the Mississippi River.

“The gym was new then,” said Ron, speaking of the WPA-built Recreation Center. “But behind it was the creek, and we’d dam it up with derelict lumber and then swim before the Health Department came and cleared it.”

The creek left Glen Canyon in an underground culvert, paralleling two-lane Bosworth Street. While Chris Mickelsen boarded a streetcar for the Embarcadero to catch a ferry for Vallejo where he built Depression-era Mare Island military housing, Ron and his friends entered the culvert, their flashlights at the ready, and played intrepid explorers.

“There was a kind of grate to keep debris out, made of old railroad ties and spaced two-and-a-half or three feet apart, but kids could easily get through it. We never walked too far, though” Ron admitted, “before we got scared and turned around!”

“My mother would always tell me not to get into any trouble when I left the house.”

Ron probably didn’t tell his mother, Anna, about the Glen Canyon horse stables either.

“There was a stable in the canyon back then,” said Ron. “There were halters and ropes hanging and there was never anyone around so we just rode the horses.”

Clearly a tale lost on his older sisters, Evelyn and Lorraine, who acted as his “little mothers.”

Leaving the canyon and following the Bernal Cut, Ron and his pals rode their bikes, their fishing poles crisscrossing their handlebars, past Dogpatch, then through Butchertown with its tanneries and saddle shops, out to where Islais Creek emptied into the Bay along with the foul by-products of the slaughterhouses and were washed away by the creek and the bay tides.

“We’d call them ‘shiners,’ but they were really perch and they’d feed on the offal,” said Ron. “We’d drop our lines off the piers and fish.”

Back home on Joost Avenue, where Anna Mickelsen sat on her porch captaining neighborhood potlucks or stood on her sidewalk showering Chris’ dahlias, fuchsias, and hydrangeas, Ron either played kick-the-can with neighborhood kids and hoped the Libby tins wouldn’t roll down Baden Street where 280 wasn’t even a glint in a highway engineer’s eye or engineered outings, using MUNI’s web of tracks and electric lines to fan out across the City.

“Our watchwords were ‘What are we going to do day?’” said Ron, thinking of that brief window before smart phones and flat screen televisions, a time when a tweet came from a song sparrow, a yahoo was a bumpkin and the only thing that went viral was pneumonia, a time when simply a 10-punch MUNI pass bought a boy a ticket to days of adventure.

“We’d hop the MUNI heading up the Chenery Street hill to 30th and Church,” said Ron. “From there we’d walk along Mission Street to the Lyceum and catch a Saturday matinee.”

“We’d take the bus through the Inner Sunset and to the museum and the aquarium,” continued Ron. “The deYoung exhibited a First World War tank and the aquarium always had the alligator.” The ferry took him to the World’s Fair on Treasure Island, the Key System transported him across the Bay Bridge to Lake Temescal in Oakland, and the MUNI whisked him to the Sutro Baths, Playland and Fleishhacker Pool and Zoo.

But he always returned to the neighborhood, to Joost Avenue, to home. “There was lots of empty land back then and we had our share of dirt roads,” Ron recalled. “There was a quarry near Baden and Mangels where people dumped junk and where we flew our kites.”

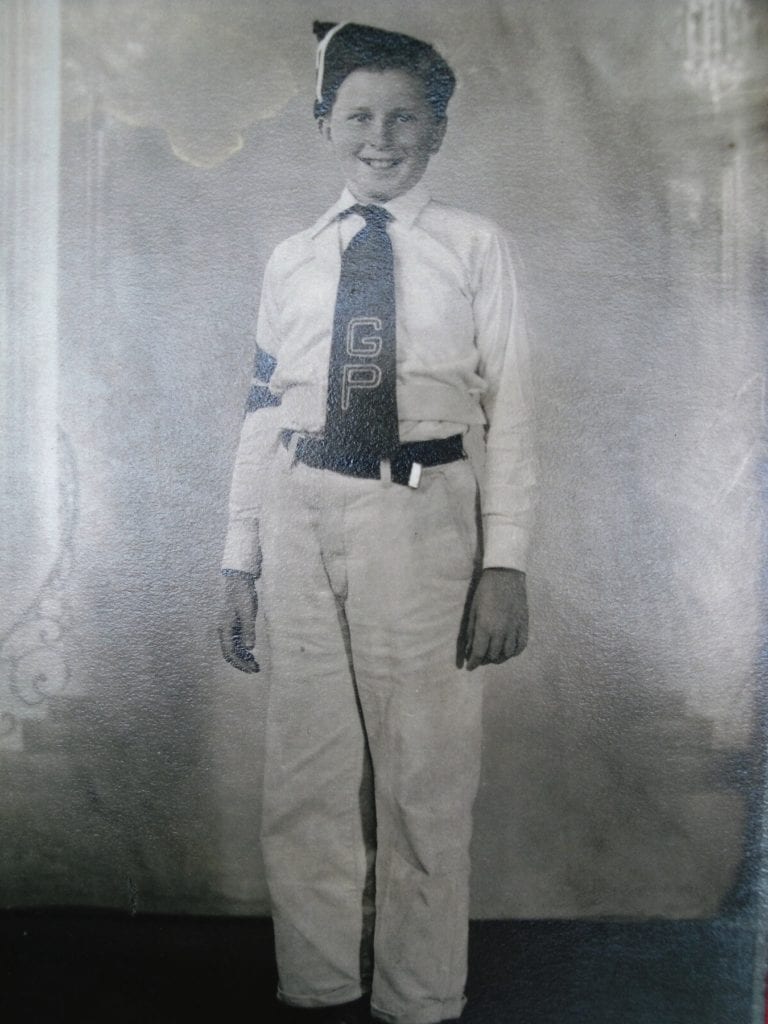

“My friend, Glen Pence, and I would jump the Monterey conservatory fence and play there. As long as I could remember it was abandoned, but behind it on the Joost estate was a machine shop and what we thought was a planetarium observatory.” Given his father’s horticultural interests, Ron parleyed his affection for plants and ventured bit farther west. “I think I enjoyed making pilgrimages to Mt. Davidson the most and watching the native Iris come into full bloom,” he said. “I grew up loving gardening.”

Pilgrimages also included excursions to Glen Park where a creamery stood where BART now stands, where a public branch library rented space on Bosworth Street across from Glen Park Elementary and where neighborhood saloons punctuated Diamond Street. His mother sent him to the Purity grocery store, better to fill up the dish plates she’d win at the Lyceum Theater.

“There was a cop who ‘stationed’ himself all day in the back of one of the bars,” said Ron. “By the end of the day when he’d walk out to check his call box on the corner he had a red nose.”

“Our principal was strict and the school was regimented,” Ron recalled. “The principal carried a long handled brass bell and made us line up and then would shout ‘Go to Class.’”

“It happened again when we needed to go to the bathroom,” he continued. “She’d line us up, our backs against the wall. There were only 12 urinals. It was tougher on the boys.”

Lorraine Monks, 89, Ron’s older sister, spins a similar tale. “We only had 20 kids in a grade,” Lorraine remembers, “and on Monday the principal would line us up on the play yard and make us recite the Pledge of Allegiance and sing the National Anthem.”

Not all of the primary school staff was so Spartan, though. Evelyn Long remembers two teachers who sent a driver to pick her and a couple of friends up and take them to Blum’s Bakery downtown. “What a treat!”

Ron Mickelsen’s school curriculum was augmented back on his own home turf. “An artist lived up Joost from us. I think his name may have been McPhearson. In the summers I worked for him, doing errands. Anyhow, his house was stocked with novels. ‘Here’s a good one’, he’d say to me, and then hand me a copy of War and Peace and The Brothers Karamazov.”

Ron Mickelsen attended Cal Poly where he majored in horticulture, and upon earning a degree was drafted and stationed in Austria at the end of the Korean War. His father Chris Mickelsen retired from home building in 1950 and he and Anna moved to the coast where in 1957 he started a Half Moon Bay Nursery on a 59-acre property, just off Highway 92. Mustered out of the U.S. Army, Ron joined the family business and with his wife, Christine, still runs it nearly 60 years later.

Ron served as president of the Half Moon Bay Chamber of Commerce and continues to be active in the creation of coast side bicycle tails and parks. Most recently Half Moon Bay honored him with the title of “Farmer of the Year,” only a little bit karmic since Chris Mickelsen had toiled on a Danish farm for 10 hours a day when he was 12 years old.

When he isn’t at his nursery, Ron travels. He just returned from Russia, arguably influenced by all of that Joost Avenue Russian literature he devoured as a boy.

Anna Mickelsen died in 1970; Chris Mickelsen followed her in 1983. No one can guarantee it, but family legend has it when Chris nicked himself shaving he bled red, white and blue, and family members will go to the bank on the fact that the ever-social Anna ritualistically left her farm house perched on a knoll, walked a distance to Highway 92 and waved at passing motorists.

Granddaughter Linda Peebles, a retired Daly City Westmoor High School English teacher who grew up in one of Chris Mickelsen’s Broadmoor Village suburban houses, remembers him, always the first to tumble from bed, when she’d visit the ranch in the 1950s. There the family Joost Avenue World War II victory garden, replete with carrots and radishes, gave way to Half Moon Bay pumpkin patches and chickens.

“I loved visiting my grandfather during the summer. We’d begin each morning listening to the “Breakfast Club” on the radio,” she said. “I’d follow him and we’d pal around together.”

“There was a big picture window and I could see trees, haystacks and horses. Later I’d help feed chickens and pick vegetables.”

Evelyn Long, Linda Peebles mother, Ron Mickelsen’s sister and Chris Michelson’s daughter died in January 2012. She was 90-years-old.

And the Joost Avenue house? It’s been sold a time or two since the Mickelsen’s left, finally in 1994 to Sally Ross, membership chair of the Glen Park Association. Pruning her holly tree one summer day in 2010, the tree Chris Mickelsen planted all those years ago, Ross noticed a family looking over her shoulder.

Graciously, Ross invited everyone inside. She seated Evelyn Long, now fragile and in failing health, in the center of her former living room. Surveying the family room, Evelyn wore a lovely cross around her neck and donned a smile as wide as Glen Canyon. She looked out the window, remembering that it was here she’d learned the love of gardening from her father who worked in a nursery in Denmark for four cents an hour.

Linda Peebles volunteered that it was in that very room her mother had listened to “One Man’s Family,” the long-running radio drama about stockbroker Henry Barbour and his family living in Sea Cliff. “She had a great smile,” offered Sally Ross. “It was very nice for her.”

Nice, indeed, for the oldest daughter of an American carpenter, remembering one man’s family that lived on a street called Joost in a neighborhood called Sunnyside.