Vandals destroyed a chicken coop atop Diamond Heights at the ECOSF student farm by the School of the Arts and smashed an adjacent beehive earlier this month.

The eight fowl —seven hens and one bantam rooster named Diego — would almost certainly have become dinner for local wildlife if not for the quick action of a neighbor who chivvied them into what was left of the coop and made a temporary door to protect them.

“They kicked in the door and then ripped through hardware cloth” around the wire mesh fencing that encloses the coop run, farm manager Tori Jacobs told the Glen Park News.

Local Hero

When Allan Pleaner, who lives on Congo Street, entered the farm grounds on July 7 through the fence hole behind a baseball backstop 50 yards from the coop run near the Ruth Asawa School of the Arts, he found the chickens free ranging, the honeybees circling their desecrated hive and several delinquents on their way out.

“There was definitely a bad vibe,” he told the Glen Park News of the adolescent yahoos who’d laid waste to the farm.

“It was like a coup in the chicken coop,” said Pleaner, who was born and raised in South Africa, came to San Francisco in 1983 and moved to Glen Park in 2003. On July 7 he watched seven pullets and Diego bury their beaks into vegetables Tori Jacobs and her high school students cultivate and harvest each year, then sell after school at a school Farmers Market each Wednesday afternoon.

“They were having the time of their lives, a total blast discovering new areas to peck away at. They were in absolute chicken heaven,” he said.

Pleaner acted quickly, knowing what would be in store for the chickens if didn’t.

Later that evening on Nextdoor, he revealed it took several go arounds to shepherd the chickens to safety.

“I managed to round them up after three attempts and to make a temporary door that required reinforcement. I doubt if they would have survived the night as the area is full of predators.”

Herding chickens, especially spooked chickens, isn’t easy. For over twenty minutes Pleaner escorted them back into their roost, not without a modicum of mayhem. A couple of the hens fluttered off and needed coaxing back to their corral.

“I know something about hens,” said Pleaner, who spent a year on an Israeli kibbutz cajoling turkeys. “The hens didn’t want to be returned to their cage. You have to speak to them calmly, gently, like hypnotizing each in a comforting way.”

Diego, the rooster, however, was having none of it.

“Diego being Diego, well, he doesn’t like being rushed,” weighed in farm manager Jacobs, who boasts a series of scars on her legs from the combative bantam’s untoward attentions. “Diego will fly at you feet first, and his two-inch talons are razor sharp.”

Pleaner corroborated this. “That rooster was very angry, territorial and patriarchal.”

“I wore jeans,” he later offered. “Diego seriously didn’t want to be reincarcerated.”

Pleaner is a couples’ counselor and practiced in the art of negotiation.

“Look,’ I told him. I can leave you out here and you’re going to get eaten. You’re not going to last the night. This will be the last day of your life.”

Diego finally succumbed to Pleaner’s pleas.

“He sort of paused, then sighed and just walked back in,” said Pleaner, who then barricaded the door and wire fence with spare pieces of derelict lumber.

Not the first but the worst

Jacobs has seen other thievery and destruction over the last several years at the farm, witnessing four benches and chairs go missing, fireworks lobbed into the chicken run, and enduring an earlier damaging hole in the coop fence and door.

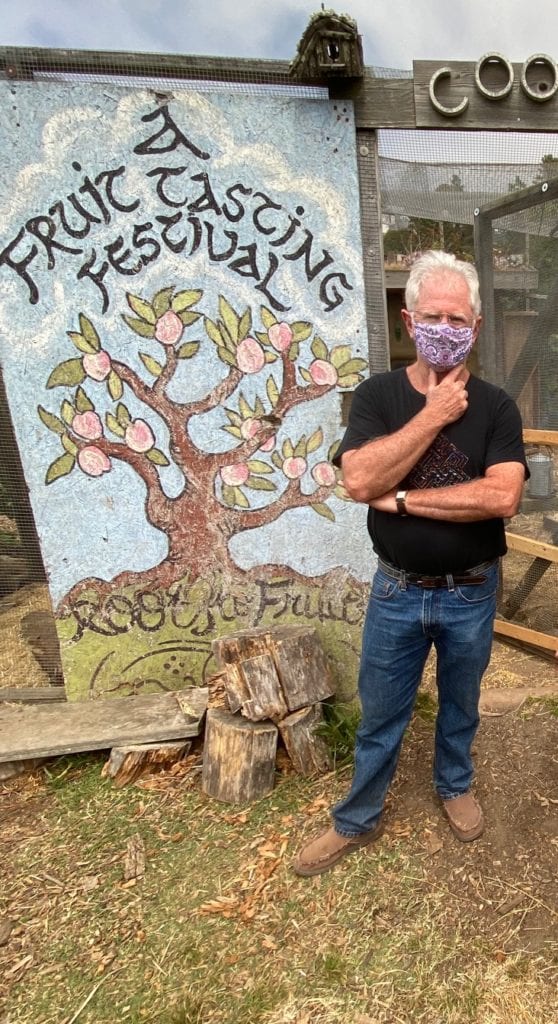

Three years ago she repaired that act of sabotage with a piece of plywood embossed with “Fruit Tasting Festival.”

“This is the worst, though,” she said.

Jacobs, who has spent 13 tending the tiny farm, visits every afternoon to check in on the brood and collect eggs.

On July 11, she stood in front of the destruction Pleaner put to rights.

“My girls wouldn’t have lasted the night without him. He’s my hero!” she said. “No chickens were harmed because of his quick work.”

While the farm’s chickens lucked out by being beneficiaries of a good Samaritan, the homeless honeybees had to wait 24 hours for their savior.

On July 8, Fernando Aguilar wheeled up to the ruined hive on his mountain bike. Aguilar’s is one of the farm’s two resident beekeepers. A Class of 1976 McAteer graduate, he harvests honey from his prolific hive and annually donates as many as 30 jars of sweetness to the ECOSF farm for sale at its weekly Farmers Market.

Aguilar braked in front of the hive and it took him only a moment to assess matters.

“The top box had been thrown off and trampled,” he telephoned the Glen Park News on July 8. “I didn’t have the equipment to suit up and put matters to right.”

Lacking protective gear and mask, he contacted his beekeeper cohort, who immediately fashioned another box.

Aguilar came to same conclusion as Pleaner.

“The bees likely would have died of exposure in more than a day or two,” he said. “When night, wind and fog come bees are protected inside beneath a roof. There they huddle like penguins to keep themselves and their brood warm.”

Jacobs and Aguilar have partnered for a decade.

When school is finally allowed to resume, she plans on enlisting students to design and rebuild the chicken coop with lumber donated by Beronio Lumber. She also plans to have students brainstorm and remodel the farm’s greenhouse and earthen oven.

Jacobs, with ECOSF nonprofit support, is used to working on a monetary shoestring, which is why she’s encouraging the public to loosen its purse strings in the wake of the recent havoc.

“I’d like to raise $200 for two 100-foot rolls of hardwood cloth that we need to replace the ruined wire,” she said, “as well as to buy the necessary screws and washers.”

Philanthropic neighbors can make donations to ECOSF at 424 Russia Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112.

Used to opening her own pocketbook to augment the ECOSF chicken feed she purchases at a 20% discount from Bernal Beast and the $15 a bale for hay she secures at Urban Farmers, Jacobs digs into her purse each week to pay for water melons and cantaloupes.

“Diego and the hens are like us,” she said. “They like something sweet.”

She’ll place a melon on the straw she changes each week, then hammers it with the heel of her shoe, which she did on July 16 as the hens and Diego circled. She stepped away and the birds happily tucked in to their sugary treat.

July 16 was also the day Jacobs greeted Pleaner for the first time since the breach.

They stood in front of the coop run, the chickens scratching and milling a yard or two away.

Jacobs offered her gratitude.

“It’s amazing what she has done here, creating a community and a precious place — chickens, gardens, and incredible indigenous and environmental structures such as the oven and greenhouse.”

Befitting our Covid-19 anxious moment where the villainous virus is more easily dispersed in an open-air classroom, he waxed philosophic.

“Coming here makes us slow down,” he wrote. “We stop and listen in such a place,” he mused, “then we wonder, then we discover.”