Mitch Badran, raised in Glen Park and a daily presence at Higher Grounds for 28 years, died of congestive heart failure on February 14th. Mitch was 82 years old. At the time of his death, he lived on Chilton Street, a house that had been in his family since 1951.

He is survived by his daughter Emily, his son-in-law, Emily’s mother Sharon Dezurick (former Glen Park library branch manager) and several nephews and nieces.

Mitch spent his 1930s and 1940s boyhood in a corner house on Laidley and Mateo Streets. He graduated Commerce High School in 1947, enlisted in the U.S. Navy and eventually became an electrical technician for PG&E, Fairchild, and United Airlines before he retired in 1982.

Family and friends gathered at his Chilton Street house on May 6th and remembered him. The common denominator threading itself through remembrances was how you could take the electrical technician and mathematician out of his laboratory and classroom but never the laboratory and the classroom out of Mitch Badran.

“There wasn’t anything he couldn’t fix,” said Marion Bellan, who babysat Emily and whose sister, Rosemary, was Mitch’s companion for decades. “Mitch was tenacious, he’d go on and on until any appliance was fixed.”

His Chilton Street downstairs garage bespoke of this. A workbench housed well-used rows of tools, each aligned in military parade ground precision, while the ceiling, crisscrossed with electrical conduits, ended in a state-of-the art service box affixed to a wall.

“After Mitch put in the wires,” said his nephew Dave Peel, “the City inspector wanted his electricians to take a tutorial from Mitch on how to do the job correctly.”

“A favorite memory I have of my father,” said Emily Dezurick-Badran, “is the inscription he wrote beneath his senior class yearbook photo. It said ‘I want to be a radio technician on the moon.’”

“I attribute most of my knowledge from Mitch to when we’d go hunting and he’d drill me on transistors.” said Dave Peel, who parlayed his uncle’s woodsy Socratic seminars into a full time instrumentation technician job in Pacifica. “We had an old black and white TV on the blink when I was a kid and Mitch took the back off it and repaired it.”

“Mitch had an amazing memory,” said Carol Badran, a niece and a 1972 graduate of Jefferson High School who teaches at City College of San Francisco. “Years later he’d volunteer things about me I’d forgotten.”

Mitch retired when Emily came along, wanting to watch her grow up.

“Emily was his life,” said Marion Bellan.

If his daughter was his life, so was mathematics. On any given morning or afternoon on any day he’d jog around Lake Merced or shoot baskets in Glen Canyon’s pit gym before arriving at Higher Grounds, settling over thumbed-through physics and calculus textbooks.

“Mitch filled spiral notebooks with math problems,” remembered Mary Huizinga, who lives on Laidley Street and often watched Mitch puzzle over differential equations while he nursed a cup of coffee. “He even notified publishers when he found mistakes in the textbook or the answers.”

“I was used to seeing him doing his numbers,” said Greg Adams, a Higher Grounds regular who lives on Foerster Street. “I’ll miss him.”

“My father made a New Year’s resolution in 1980,” said Emily, holding several of Mitch’s handwritten diaries and journals. “He promised to make an invention a day, one thing a day for an entire year.”

She fingered one of Mitch’s carefully written journals.

“He made it only to March 31st,” she smiled.

“Mitch built a Barbie doll house for Emily,” said Mary Huizinga, who often walks her dog Chester through the village. “He even installed a working elevator!”

“Mitch kept everything Emily ever did,” said Dave Peel, as he walked through Mitch’s garage. Kitty-corner to Mitch’s wrenches, hammers, screwdrivers and pliers, across the room from deer antlers he had accumulated from countless hunting trips to Mendocino and Humboldt counties, hung memorabilia from Emily’s school years.

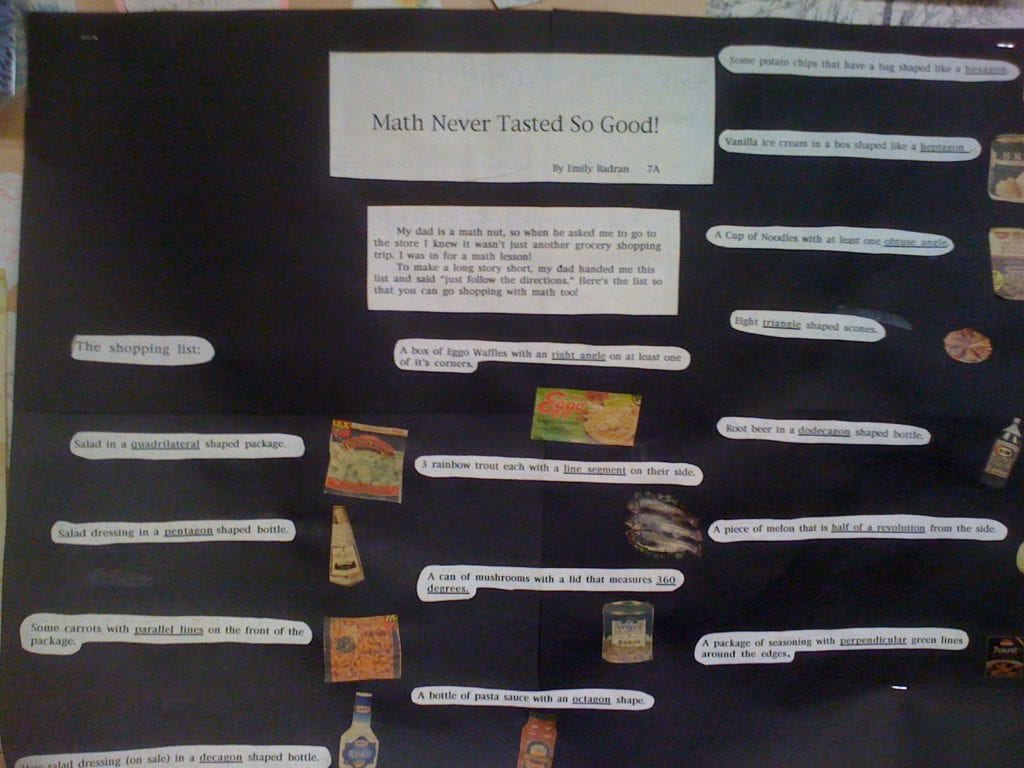

Tacked to a garage wall, testimony to his affection for his daughter, a collage Emily made stared out, entitled, “Math Never Tasted So Good!”

Tacked to a garage wall, testimony to his affection for his daughter, a collage Emily made stared out, entitled, “Math Never Tasted So Good!”

Liking his routines, even his solitude, but not so much that he wouldn’t occasionally sacrifice each to travel with Rosemary, Mitch was disciplined, especially about his health.

“At a time in the 1970s when it wasn’t common for people to be in shape,” recalled Greg Adams, a Balboa high school graduate, “Mitch would shoot hoops at the gym by himself for hours.”

“He never missed a shot,” said Manhal Jweinat, owner of Higher Grounds, “and he always watched his weight.

“Mitch was a health nut and so disciplined,” agreed Marion Bellan. “He’d eat a donut and throw half of it away.”

“Mitch would go to Greenbrae and swim in Rosemary’s backyard pool,” said Dave Peel, who attended Sunnyside Elementary and Riordan High School, “and because it was so small he’d do a gazillion laps.”

On May 6th, Mary Huizinga handed one of Mitch’s diaries to a neighbor, who leafed through it, randomly selecting a page from 1980.

Mitch had inscribed:

“January 2nd – Built a can opener. January 4th – Built a clock. January 6th – Built a shampoo holder. January 8th _ Built a screwdriver holder. January 21st – Built a handle for garage door.”

“Mitch was comfortable with himself, always stoic, and he wanted no speeches,” said Dave Peel. “He wanted to keep things simple.”

An entry from another of Mitch’s journals, though, this one dated September 18, 1964 speaks to matters that were anything but simple. Mitch wrote:

“Trig class tonight. Sure going to keep us busy. Our workbooks are from the University of Nebraska. We have 88 problems over one-and-a-half weeks. Each problem contains many others.”

Mitch dressed as simply as he conducted his life, commonly seen in his familiar warm-up jacket zippered over a T-shirt.

“When we went through his things,” said Carol Badran, “we found so many T-shirts with the American flag on them.”

Understated as he was trim and fit, Mitch didn’t wear his patriotism on his sleeve, only close to his heart.

Family and friends scattered Mitch’s ashes beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, along with rose petals on March 24th.

“Afterward we celebrated his life with a bit of Armenian brandy,” Mary Huizinga said.

“To Mitch,” everyone toasted, keeping it simple. “It was great knowing you.”