“We’re in a major health emergency and neighbors looked around and asked, ‘how can I get involved, how can I help my community?’” Joan Lasselle told the Glen Park News on August 13.

Lasselle, who has lived on Laidley Street since 1987, is a charter member of It Takes a Village, a nonprofit that credits its name to an African proverb prompting an entire community to interact with children so each can grow in a safe and healthy environment.

Now, six months into a pandemic that has claimed 181,000 American lives, the African dictum is as relevant as ever.

While children remain at risk, the population disproportionately in harm’s way — the ill and the housebound most susceptible to isolation and anxiety — are drawn from an older demographic.

“How can I support those people most vulnerable, the people not well served?” Lasselle wondered.

Her answer was to get masks into the hands of hospitals and health facilities as soon as possible.

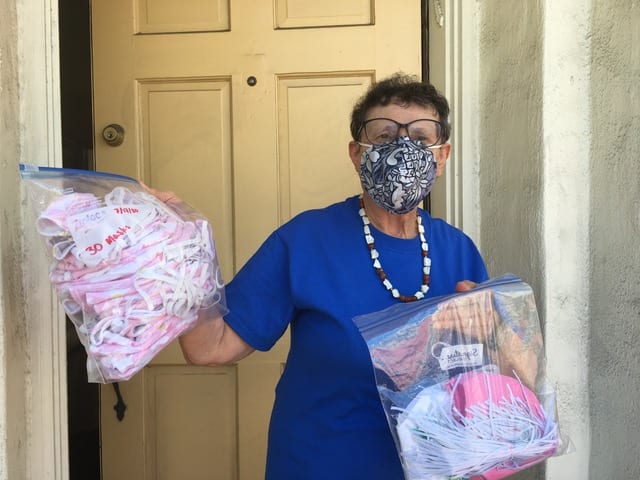

Lasselle has been working to collect some 175-200 masks being sewn by Glen Park residents each week to hospitals and medical facility first responders throughout the region.

Her 10 Glen Park seamstresses, or “sewists,” as she calls them, have been working since March.

“During the week of August 17 we sent 825 face masks to hospitals throughout San Francisco, San Mateo and Alameda Counties,” Lasselle told the Glen Park News, “with a portion of last week’s effort finding its way to Salinas farm workers.”

Used to traveling to Silicon Valley where her IT company provided tech support to Bay Area businesses, since the mid-March lock down, Lasselle has instead traveled throughout Glen Park and surrounding neighborhoods delivering sewing kits to sewers on Randall, Arlington, Bosworth, Flood, Detroit, Melrose, Chaves and Diamond streets.

Lasselle delivers one kit a week to seamstresses. “Each kit is made up of cut cotton fabric, elastic and nose wire.”

The ITAV origin story began this March, on the heels of a historic health crisis we’ve not seen the likes of since 1918.

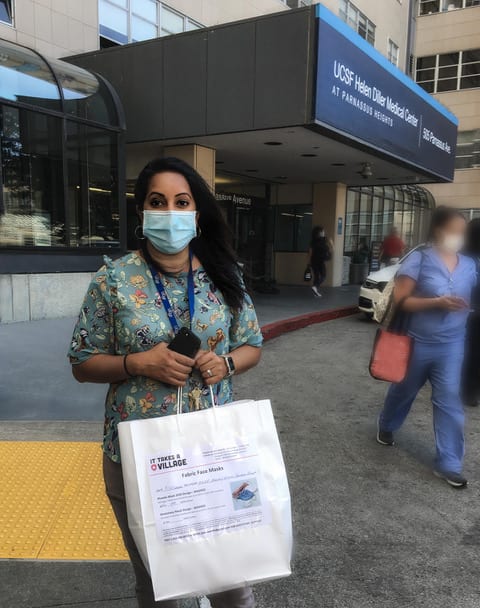

Its sole mission is to assemble a volunteer community that fashions and delivers masks to health care workers who support underserved populations.

“We were founded by Shelly Wong, an Alameda entrepreneur, who pulled me in, Eva Camp, Julia Chin and Sheryl Stuart to form the leadership team,” said Lasselle. “Like all startups, everyone does what’s needed to keep things going. Julia manages the sewing including putting together kits, Eva manages assembly of face shields, packaging and coordinating deliveries, Sheryl focuses on marketing and communications and Shelly and I coordinate to whom we donate.”

Wong, after learning from an emergency room doctor at Zuckerberg San Francisco General on March 14 that there was a critical need for PPE, was fast off the mark.

Since its inception ITAV has delivered to its Bay Area recipients a staggering 39,942 masks and 11,625 face shields.

“Shelly said ‘I have to do something,’” Lasselle said. To date, ITAV has enlisted 240 volunteer sewers and raised $38,000 through GoFundMe with a goal of making 1,000 masks a week.

It has even been on the receiving end of Coca Cola largess. The soft drink behemoth and other companies donated polycarbonate to ITAV so it can fabricate its protective face shields, using Boy Scout troops to staff the production line.

Susan Tauber, who with her husband Hal owned Glen Park Hardware until their retirement in 2016, is one of Lasselle’s neighborhood volunteers.

“I collect Susan’s masks on Friday, then launder them with others at a high temperature, then press each,” said Lasselle. She then counts, sorts and eventually delivers them to hospitals and health care providers. The masks go to essential workers and sometimes to discharged patients or patients coming in for routine doctor’s office appointments.

Reached by the Glen Park News, Tauber shared that she’s been stitching since early June.

“At first I was an amateur, so I clicked on a YouTube video and learned how to make them,” said Tauber, who since retiring has traveled to China, Canada, Israel and Jordan. “I had to retrieve my sewing machine from Melissa, our daughter, and early on I managed only 15 masks a week, but now I’m up to 30.”

Rummaging through closets to retrieve pin cushions and needle packets, Tauber was slow at first off the sewing machine peddle. Now she takes just 20 minutes to complete a single mask.

When asked why she took on the sewing gig, Tauber’s response was simple.

“I had the skills and the tools and I wanted to be useful,” she said, recalling she’d been first introduced in Boston to measuring tape, pin cushions and button cords in her elementary school fourth grade class.

Lasselle and Wong are both entrepreneurs and organizational know-how is second nature to them.

Lasselle filled her Glen Park roster of eager volunteers with needle and thread talent the old-fashioned way.

“It’s really nothing more than word of mouth and Sales 101,” said Lasselle, relegating social media momentarily to the sidelines. “It’s a lot of networking and our leadership team meets regularly.”

She’s certainly not technology phobic as befits a Silicon Valley maven.

“Three student volunteers have made notable contributions,” she said. “Chelsea Camp, who is Eva’s daughter, is a high school eleventh grader in Oakland and she designed, built and continues to maintain our ITAV’s website.” (www.it-takes-a-village.org), while Jack Chan, Julia’s son, a high school junior, coordinates volunteer efforts with his Boy Scout troop in Piedmont.”

“And Tyler Markovich, a film student at Tufts University,” Lasselle continued, “created a promotional video to tell the ITAV story.”

She goes on to describe ITAV’s leadership team as non-hierarchical.

“I suppose you could we’re a very flat organization,” she said, which given how Dr. Anthony Fauci urges us all to flatten the coronavirus curve isn’t such a terrible idea.

“We operate on in-kind donations,” said Lasselle, who culls discarded linens from peninsula hotels, as well as garnering new fabric from BrynWalker in Berkeley.

“We’re all about being volunteer, rapid response and grass roots,” she continued, conjuring up images of the World War II home front when American can-do ethos spawned victory gardens, rationed gasoline and meat, and witnessed thousands of women enter the work force to become essential to United States munitions and armament manufacturers.

At its origin, Laidley Street, named for Scotsman James Laidley who came to California in 1851 and became an elected San Francisco harbor commissioner, meanders around the eastern edge of Glen Park, stretching south from Noe Valley, separated from Bernal Heights on the east by San Jose Avenue. It’s there, on the first block that Dot Adams resides, across the street from the once infamous Gray Brothers quarry and a block from the Harry Street stairs.

Adams lives in what she believes is a 1906 earthquake shack — one of hundreds of tiny, inexpensive houses built right after the 1906 earthquake.

“We were told the house was built in 1907,” Adams told the Glen Park News while sitting on her cottage porch, which shares the cityscape with houses many times its size.

Like Tauber, Adams makes masks and it took some work for her to retrieve spools of cotton thread, needle threaders and mending floss sequestered in a sewing box in a hall closet.

“I’m not a seamstress and the last time I’d used my sewing machine was 12 years ago to make throw pillows,” Adams told the Glen Park News by email. “Making masks made sense to me right away, despite the government’s assertion at the time that they did little to fight the coronavirus spread.”

The first mask she made was for her husband. It was by no means perfect but a point of pride nevertheless given she had to scrounge for materials.

“Elastic was difficult to find,” she said. “So, I improvised and used the elastic from one of my old bathing suits.”

That’s when she decided to take a page from Tauber’s playbook and go online for a YouTube tutorial.

“I realized in order to be more effective I needed to dust off my sewing machine,” she said. “The first week of mask-making was a huge learning curve. My machine’s ‘footer’ broke and wouldn’t engage and I broke three needles!”

Adams’s learning curve wasn’t as steep. She began to fashion masks next for her seven siblings spread across the country. Then she began to think larger still.

Adams, who has lived in her Laidley Street bungalow for 19 years, broadened her horizons.

She put up a brief post on Nextdoor for Glen Park.

“It is now required to wear a mask in most circumstances when outside. If you need a mask I can make one for you.”

Denis Wade, a long-time Glen Park News editor and an octogenarian, read Adams’s message and made contact. Wade, whose copy editor prowess catches glitches such as confusing the word ‘your’ with the contraction ‘you’re,’ had earlier tapped into St. Aidan’s Episcopal Church’s Friday pantry pre-bag-food-and-hand-it-out-the-door lunches.

“Dot and I connected by phone and she immediately hopped into her car brought me two masks, complete with HEPA filters,” emailed Wade, who lives on Diamond Street.

“Having a mask with a filter makes me feel better about taking BART to my next dental appointment,” said Wade, who sharpened his journalistic skills in the 1960s at the San Mateo Times and NBC News.

As the fires now ravaging Northern California caused public health officials to urge seniors to remain inside during what the San Francisco Chronicle reported on August 20 as the “worst air quality in the world,” Wade found that Adams’s HEPA mask kept smoke at bay.

“To cope with cabin fever, I have a ‘mental ankle bracelet’ I’ve slipped off a couple of times to sneak out to the supermarket,” he admitted, “but always wearing Dot’s mask.”

Those masks are made of double layered quilting cotton with a pocket for filter and a bendable metal piece at the nose bridge. Since she began working in front of her sewing machine she has fashioned 160 of them, dipping into her own purse to the tune of $500 for the fabric.

“I wash my hands before and after I deliver and put each mask in a zip lock bag and place each in a designated mailbox or reach through the passenger seat window and hand them off.”

She’s so far delivered nearly 100 masks to Glen Park residents.

On her daily walks with Monkey, her 12-year old poodle-mix, she sometimes leaves masks on home door knobs.

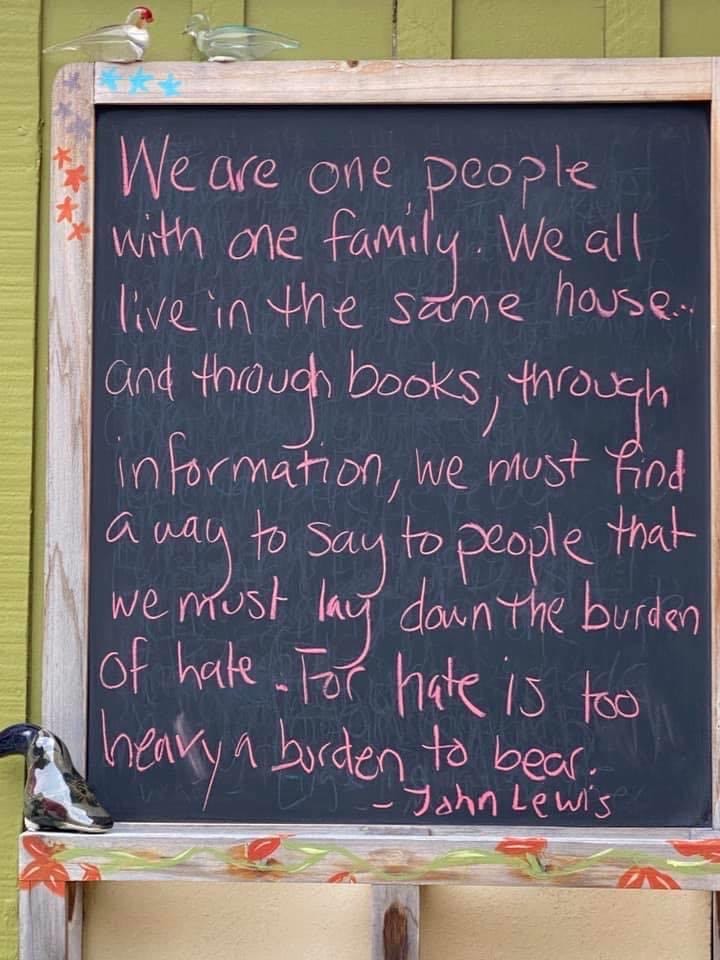

A step or two from her front door hangs a chalkboard where she’s in the habit of placing several of her masks each day. By sundown they’re gone.

“For me it’s all about community, making connections,” she offered on August 19. “I feel a compulsion to get people to wear a mask.”

Mindful of the maxim, united we stand, divided we fall, she added:

“You protect me, I protect you.”

Dot Adams has another takeaway.

“What I’m most proud of in terms of ‘giving’ during this unprecedented time is my “Giving Tree’ mural and my chalkboard,” she said.

Her mural is festooned with flowers that are photos she’s taken of neighborhood flora, while the tree itself is painted with acrylic paint and the leaves are magazine cut outs that have weathered well.

“I call it my ‘Giving Tree’ because the pandemic has taught me a lot of things about myself and others,” she said, “and if there’s a silver lining, it’s the more you give the more your receive.”

Her chalkboard is a miniature version of what one would see in American classrooms, if schools weren’t in lock down.

“For a few years now I’ve left quotes on the board that resonate with me. But since the quarantine I’ve written what I think all our neighbors can relate to during this specific time.”

Not that long after she began fashioning protective masks, Adams borrowed a thought from Herman Melville, which she believed is particularly salient given her new avocation, our anxious moment, and how Melville’s meditation folds into the very roots of her ‘Giving Tree.’

“We cannot live only for ourselves,” Adams quoted Melville. “A thousand fibers connect us with our fellow men; and among those fibers, as sympathetic threads, our actions run as causes, and they come back to us as effects.”