By Murray Schneider

On November 27th, Elizabeth Boardman, 70, returned to Bird and Beckett and read and signed her latest book, I’m Not a Tourist, I Live Here! She was accompanied by Doc, a dulcimer-playing street minstrel whom she’d befriended over a decade earlier while commuting from her Glen Park home to her Tenderloin office.

Boardman, until her retirement and subsequent move to Davis, worked as a social worker at North of Market Senior Services; Doc continues his strumming each morning at the Civic Center BART station, which he’s done now for nearly 20 years.

Boardman moved to her Chilton Avenue “cottage” in 1996, remaining there until 2009. Riding BART to her job each morning, she walked through the gritty Tenderloin, navigating among its denizens, some homeless, others drugged-out or hung-over, still others jobless or delusional, most without hope.

Now she’s authored a book that describes a San Francisco that tourists, far off Frommer’s radar, rarely experience.

“It started 20 years ago,” she told an audience of 25 Bird and Beckett readers, “when I saw a T-shirt I didn’t buy, to my lasting regret. Across the front, it said ‘I’m not a tourist, I live here!’”

As a social worker, she provided services to the disadvantaged, the elderly and the frail.

Her new book serves up vignettes depicting too many men who once tipped the scales as vigorous light heavyweights but now, shabby and toothless, worn down and sometimes threatening, mill together in scarecrow-thin stupors around klieg-lit liquor stores and rundown SROs. She writes of back alleys and mean streets where too much wine is consumed, too many drugs are exchanged and too many working girls barter their services.

Boardman’s 1963 Harvard University bachelor’s degree in American history didn’t prepare her for what she’d encounter during her professional career.

Through it all, though, she hasn’t lost her faith in the basic decency of people, recounting the story of an immigrant Jamaican laborer hired to guard a construction site where one of her centers was scheduled to open. Carrying equipment to the facility, she sliced her hand on a knife lying in the trunk of her car. The young guard calmly bandaged her hand and then kindly offered her a cup of water.

“He took care of me,” Boardman said. “I don’t remember his name and I never saw him again.”

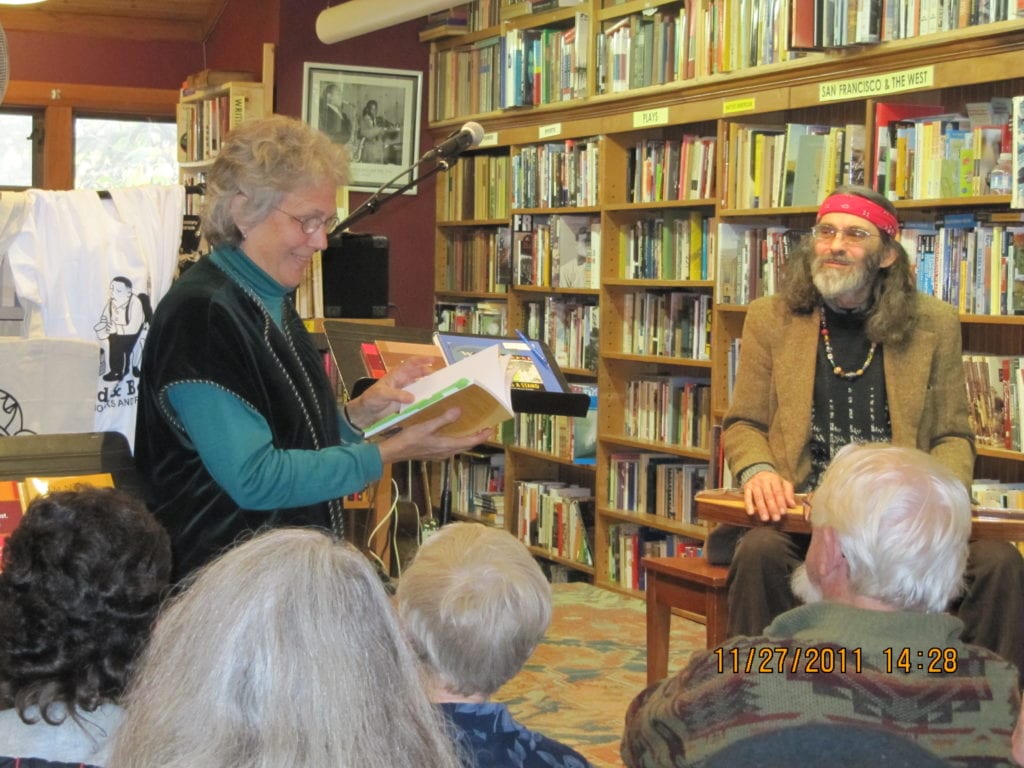

She met Doc early on, as he jockeyed for “stage” space in the well-trafficked Civic Center BART station. The day of the reading, Doc peered through owlish eyeglasses. He was dressed in a brown Harris tweed coat that didn’t quite disguise the hippie-dippy necklace looped around his neck. His shoulder-length hair, held in place by a red bandana, complemented a manicured salt and pepper beard.

He looked like a skinny Excelsior District Jerry Garcia, sans guitar.

As Boardman read, Doc strummed his dulcimer, which made a sweet and gentle sound, his beatific smile in honeyed harmony with his dulcet tones that waffled through the bookstore.

Doc looked as if he’d have been at home on the corner of Haight and Ashbury in its halcyon days, just as he now seemed comfortable straddling a stool in a hip real-time Chenery Street bookstore.

“I’d give Doc a dollar each morning as I passed him,” Boardman said. Sitting behind her, Doc plucked his trapezoidal-shaped instrument, which fittingly means “sweet melody” in Latin.

Doc rested his dulcimer on his lap and looked up.

“People are more willing to help in the morning,” he said, framed by shelves of Eric Whittington’s travel books. “In 1984, I exchanged a cherry wood hash pipe for my dulcimer.”

A U.S. Army vet who once called Michigan home, the elfin 64-year old street musician now lives at 26th and Folsom Streets with his girlfriend. He uses his daily panhandling earnings to supplement his SSI check.

“I need $10 a day for some veggies and a beer for me and my girl,” he said, sounding very much like a City Lights Beat poet from so long ago. “Even if you win in the rat race, you’re still a rat!”

Doc, who performs for two hours every day, meditates longer about his celestial cannabis.

“Pot is God’s medicine, mental health and muse,” he said, looking at Carlos Ramirez, 73, a friend who’d accompanied him to Glen Park and who often turns up at Jack Hirschman and Lawrence Ferlinghetti North Beach poetry readings.

Ramirez sat in the front row, surrounded by Boardman’s friends and social worker colleagues. Dressed in a black T-shirt lettered “Cheap Fashion Here,” Ramirez sported a bushy white beard.

Like Doc, Ramirez looked as if he hadn’t a care in the world.

“Doc has a sweet persona, a friendly greeting presence that mirrors my own humanity back to me,” he announced with New Age insouciance.

The same might be said for Elizabeth Boardman.

Bookseller Whittington, who has known her for six years, stood behind his counter while he rang up sales of Boardman’s book.

“Elizabeth personifies sincerity and activism, two parts of a wonderful whole,” he said.

Vera Haile, Boardman’s supervisor for 12 years, who watched her build-to- capacity a private non-profit from one to four offices and then minister to underserved and underepresented seniors on both the north and south side of Market Street, echoed Whittington.

“Elizabeth is marvelous,” Haile said. “She initiated new senior housing, pressuring the City to begin low income housing in Mission Bay.”

A Quaker, mother to four children and grandmother to seven grandchildren, Boardman, a pacifist, asks nothing of anyone that she wouldn’t do herself. In 2002, at considerable risk, she traveled to Baghdad to register her non-violent beliefs.

“She’s a wonderful person,” said Reverend Glenda Hope of the San Francisco Network Ministries. Hope sat in Bird and Beckett’s audience in support of Boardman, who served on her ministry’s Board. “She walked the talk, risking her life.”

In the end, though, Boardman returned to Glen Park, her ‘hood, taking time to recall what really makes a community.

“I moved to Chilton Avenue from Cesar Chavez Street, where hardly anyone knew his or her neighbors,” she said. “Here, within two weeks, I was introduced to half the people on my block.”

Block parties followed, then neighborhood watches, even a bevy of celebratory New Year’s parties over the years. Fruit trees, fig, lemon, orange, even grapefruit, were plentiful in Chilton and Lippard Avenue backyards, and exchanges among neighbors are still common.

“I shared the cost of trimming a plum tree that grew on the property line with my neighbor,” Boardman said, where the bungalow she once owned on the cul-de-sac still remains nestled behind a white picket fence. “Another neighbor would climb my Gravenstein tree and eventually apples, even slices of apple pie, were doled out among neighbors.”

On the way to BART each morning, she passed Jorge, carrying his boxes of potato chips to the Blue School’s vending machines, and befriended Millicent, the school crossing guard, plying her trade at one of the busier transportation hubs in the City, raising her patented red stop sign and escorting herds of children and commuters across Diamond Street.

Compared with the Tenderloin, Glen Park was predictable, but it, too, could serve up the unexpected, Boardman revealed.

“I walked to work one morning as usual,” she told her audience, “and I noticed a group of people gathered outside the corner market across from BART.”

Inside, on the floor, an elderly man, dressed in sweats, lay unconscious. A young woman knelt by his head, juggling a cell phone while she checked his pulse.

Boardman paused, taking a breath.

“I always wondered how I would deal with a situation such as this,” she said, as she looked for the dog-eared place in her book that referenced the incident.

She exchanged a few hurried words with the young woman and then they both began CPR, the young woman performing the breathing and Boardman doing the compressions. They continued for what seemed forever.

“I could feel ribs breaking as I pressed. Then suddenly the EMTs were pushing us aside.”

The young woman, it turned out, was a nursing student who was walking past. The sweat-suited senior, Boardman learned later, was pronounced dead. His family had once owned the market, and he’d returned to buy a newspaper and reminisce. His daughter, worried that he hadn’t returned home that day, posted LOST signs up and down village streets. While she mourned her father, she was pleased at such closure, the karma of it all.

“This story pleased the corner store’s owner, as well.” Boardman said, closing her book. “And I liked it, too.”

At the audience’s request, Doc had accompanied her through her final selection.

“Elizabeth, you write with a loving pen,” he said. “Thank you for including me on your book’s cover.”

In the front row, Carlos Ramirez looked pleased.

“Doc,” he said. “You’re a poet!”

Boardman peered over the heads of the audience, looking for Bird and Beckett’s owner.

“Eric has been so supportive of this neighborhood,” she said, stepping from the stage and reaching for a copy of her book, which was handed her to sign.

If Boardman had thought to record this Age of Aquarius independent bookstore love-in, her off-the-tourist-track detour to her former neighborhood would make a notable first chapter in her next book.

When she completes it, she’ll have little trouble finding outlets to distribute it.

Bird and Beckett, of course, will sell it.

Doc will, too. He’s had lots of practice selling her books. Pass through the Civic Center BART station any morning, listen to him strum his dulcimer for a minute or two and then purchase a copy of I’m Not a Tourist, I Live Here!, a miscellany of San Francisco visitors hardly ever see, but Doc experiences every day.