Story and photos by Murray Schneider

This winter 18 San Franciscans braved cold temperatures that dipped into the forties and listened to Evelyn Rose of the Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project spin tales from Glen Canyon’s past on one of her patented Glen Park history walks.

Rose, who writes a Glen Park News column called “(HI)STORIES OF OUR NEIGHBORHOODS,” recounted stories that included a dynamite disaster, Gilded Age dairy cows prodding to Portola Drive, and gravity-fed Islais Creek flumes that once supplied San Francisco with up to eighty percent of its water.

Rose rendezvoused with her history buffs at the park’s Elk Street entrance. Many were bundled in wool, flannel and fleece. They each wore sturdy walking shoes and some carried water bottles.

“The core goals for the Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project, covering Glen Park, Glen Canyon, Sunnyside, Fairmount and Diamond Heights,” Rose told them, “is to rediscover our forgotten history, document our living history, and share our history with others.”

Rose titled her history tour: “Bovines, Dynamite, and High-Flying Shows: The Amazing History of Glen Canyon Park.”

By the end of the three-and-a-half hour history walk, her audience wasn’t disappointed.

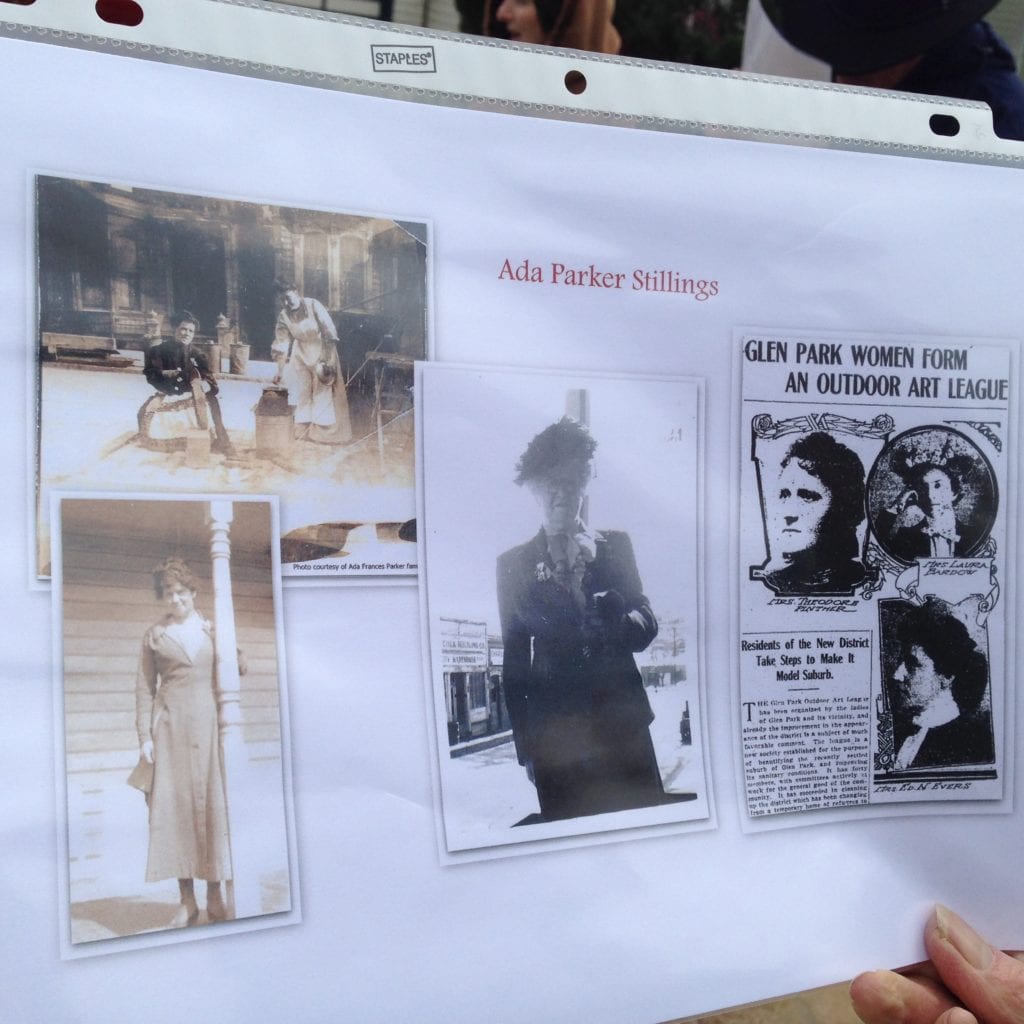

Evelyn Rose’s storyboard is rich in anecdotal neighborhood folklore, filled with eccentric characters and populated with hucksters, heroes, hustlers, heroines, engineers, entrepreneurs and environmentalists.

Her first story, right off the page, fit the bill.

In March 1868 Alfred Nobel licensed his nitroglycerin patent to Julius Bandmann who then leased the property to L.L. Robinson to establishe a manufactory of 25X60 feet, and four other buildings in the dynamite operation, with an eight-foot fence surrounding the one-acre property near today’s Bosworth Street park entrance. Nobel, who had earlier experimented with nitroglycerin, hired a chemist, an assistant, a teamster and Chinese laborers. Two years later, on November 29, 1869, an explosion, which could be heard as far off as Chenery Street and Lippard Avenue, ripped through the facility and resulted in two fatalities. Both the chemist and the teamster perished.

“This was the era of canal and railroad public works construction and dynamite was prized,” explained Rose. “The Glen Canyon explosion caused a huge flash of light that could be seen as far off as downtown.”

Rose continued her 1.2-mile excursion, leading her group along Alms Road. She pointed to parched Islias Creek, which begins on southern slopes of Twin Peaks and eastern slopes of Mt. Davidson. Directed through an underground culvert beginning at the WPA-built Rec Center, Islias Creek now empties into the bay with the East Bay hills in sight.

“When it ran above ground the creek supplied up to eighty per cent of San Francisco’s water,” explained Rose, “and was carried all the way downtown by gravity-forced flumes.”

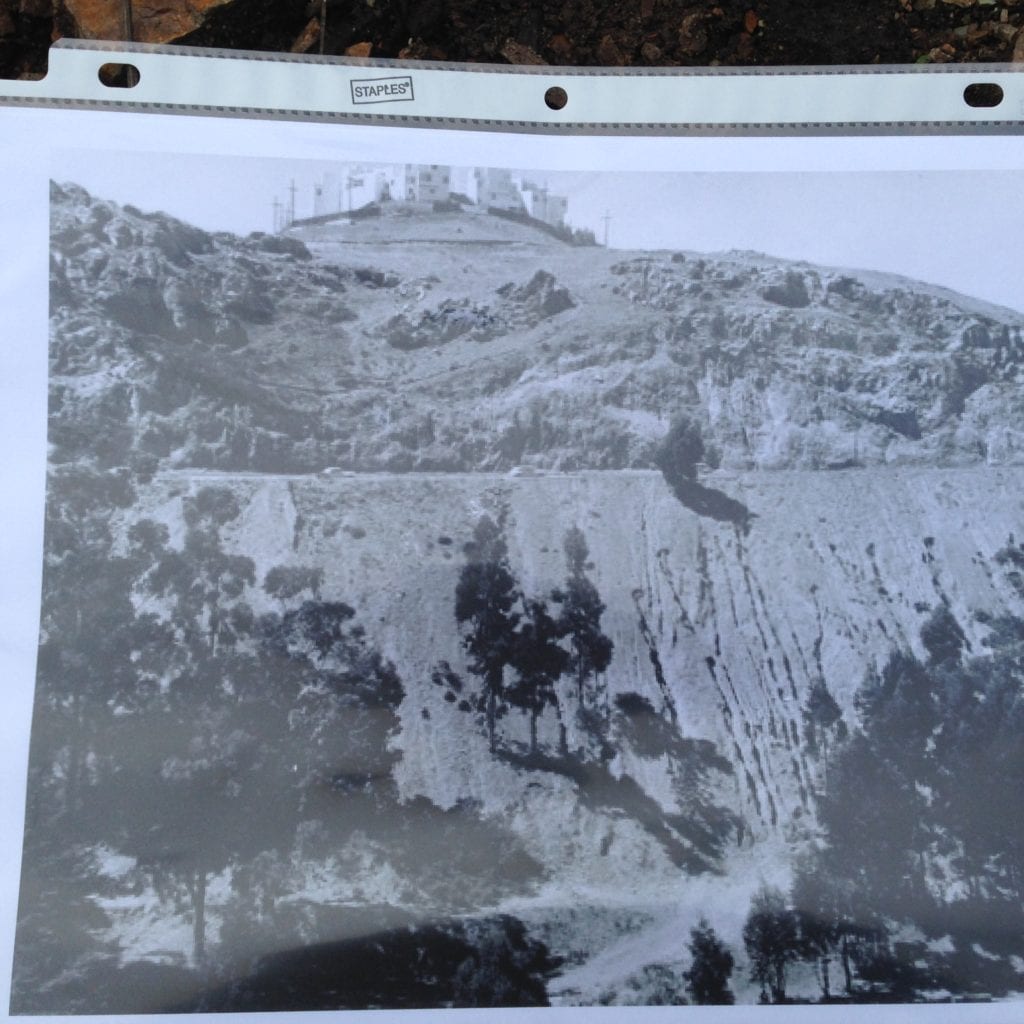

A bit farther north the group ascended box steps, gaining the saddle trail that straddles Franciscan chert rock outcrops.

Here Evelyn Rose surveyed vistas in each direction. Behind her, across O’Shaughnessy Boulevard, on a 600-foot high promontory loomed El Sereno Court, a cul de sac on Mt. Davidson, fashioned with the same earthquake impervious bedrock on which she now stood. Immediately above Rose hulked Diamond Heights. To her north stood the football scoreboard at Ruth Asawa School of the Arts.

“We can see a lot from here,” Rose said. “In the 1880s a dairy farm, Gardiner’s Ranch, operated on this slope.”

The earliest record of John Holmes Northrup Gardiner harkens back to 1860. The Rhode Island native milked his share of canyon dairy cows with the assistance of five employees, later moved to Montgomery Street and eventually returned to Rhode Island where he died in 1894.

“Down below,” said Rose, “Silver Tree summer camp just celebrated it 75th anniversary and to our north there was once a golf driving range where SOTA now is.” “Climbers called these rocks Miraloma rocks,” she said, “and as early as the 1930s rock climbers from Stanford, Cal and the Sierra Club came here and challenged them.”

As she had done at earlier talking points, she circulated a photograph, this one showing a group of collegians repelling from the cliff’s face.

Rose doubled back, using box steps, preferring them to stringer steps.

Once there, she and her followers navigated the eastern side of Islais Creek, demarcated by a split rail fence constructed by Richard Craib and Friends of Glen Canyon Park in the early 2000s. She stopped at what looked like a horseshoed-shaped campfire pit, camouflaged by English ivy and California blackberry.

“I think this may have been a water trough for Archibald Baldwin’s zoo animals,” she said.

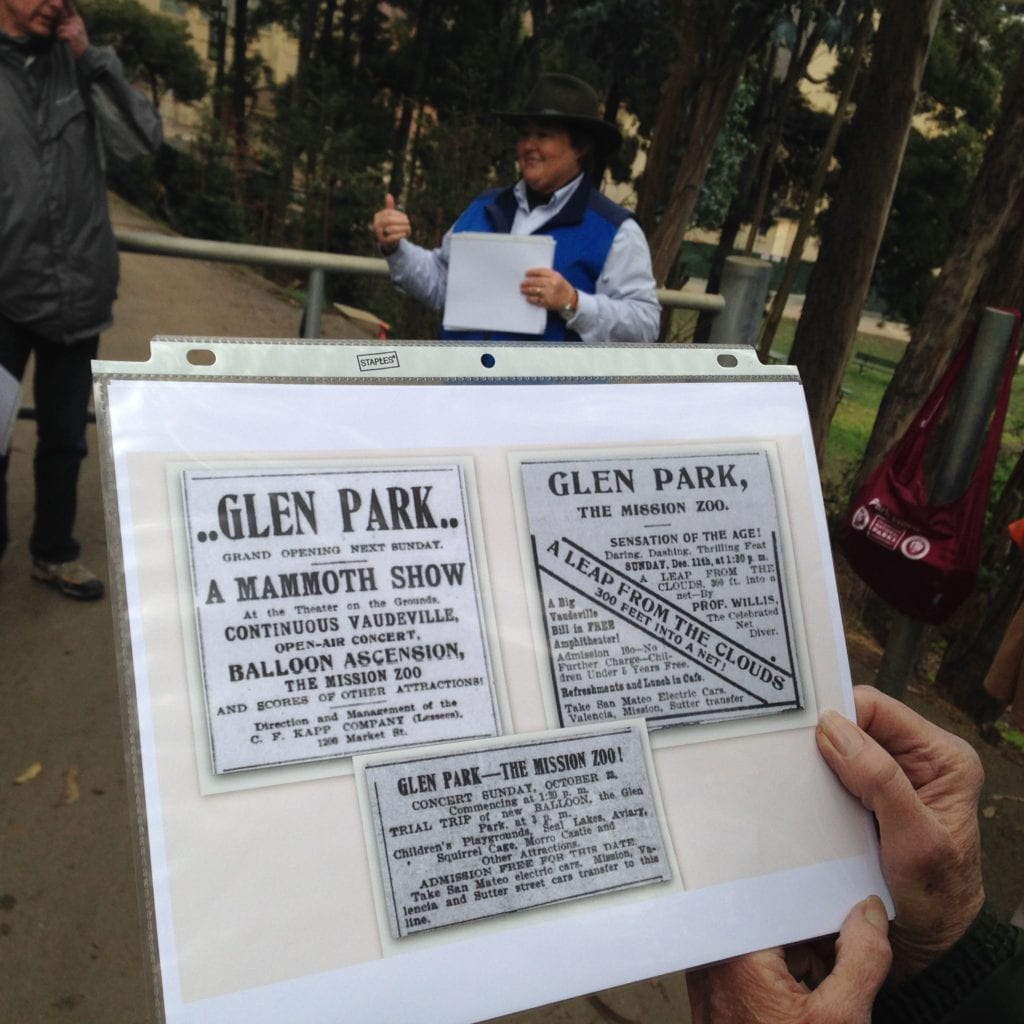

Archibald S. Baldwin would find no trouble fitting in with today’s San Francisco’s construction boom. A 1890s businessman and pugnacious real estate developer who would go on to build much of Mt. Davidson, St. Francis Woods, Westwood Terrace and Westwood Highlands, Baldwin encouraged perspective city blue collar home buyers to hop a Behrend Joost’s streetcar for a nickel, step off at Chenery and Diamond Streets, and walk the length of Chenery Street to Elk Street. Baldwin was banking they’d take a flyer on one of his 75 – 25’ X 100’ lots he proposed unloading for $250 to $350 each.

“A.S. Baldwin proposed building a great zoo to make the lots more saleable,” said Evelyn Rose, “and populate it with all sorts of exotic animals.”

Baldwin wanted his Mission Park and Zoological Gardens to become home to black bears, kangaroos, baboons, hyenas, coyotes and foxes. He envisioned his menagerie evolving into an open-air Mecca for the City’s working class. His scheme was too grandiose for City Hall, though, and before he was forced to downsize, the quarrelsome developer slugged it out with Charles Clinton, an obstreperous city supervisor. No pushover, Clinton landed a jaw-jarring blow to the side of Baldwin’s face. The mayor, James D. Phelan, adopting the roll of referee, separated both bare-knuckle pugs.

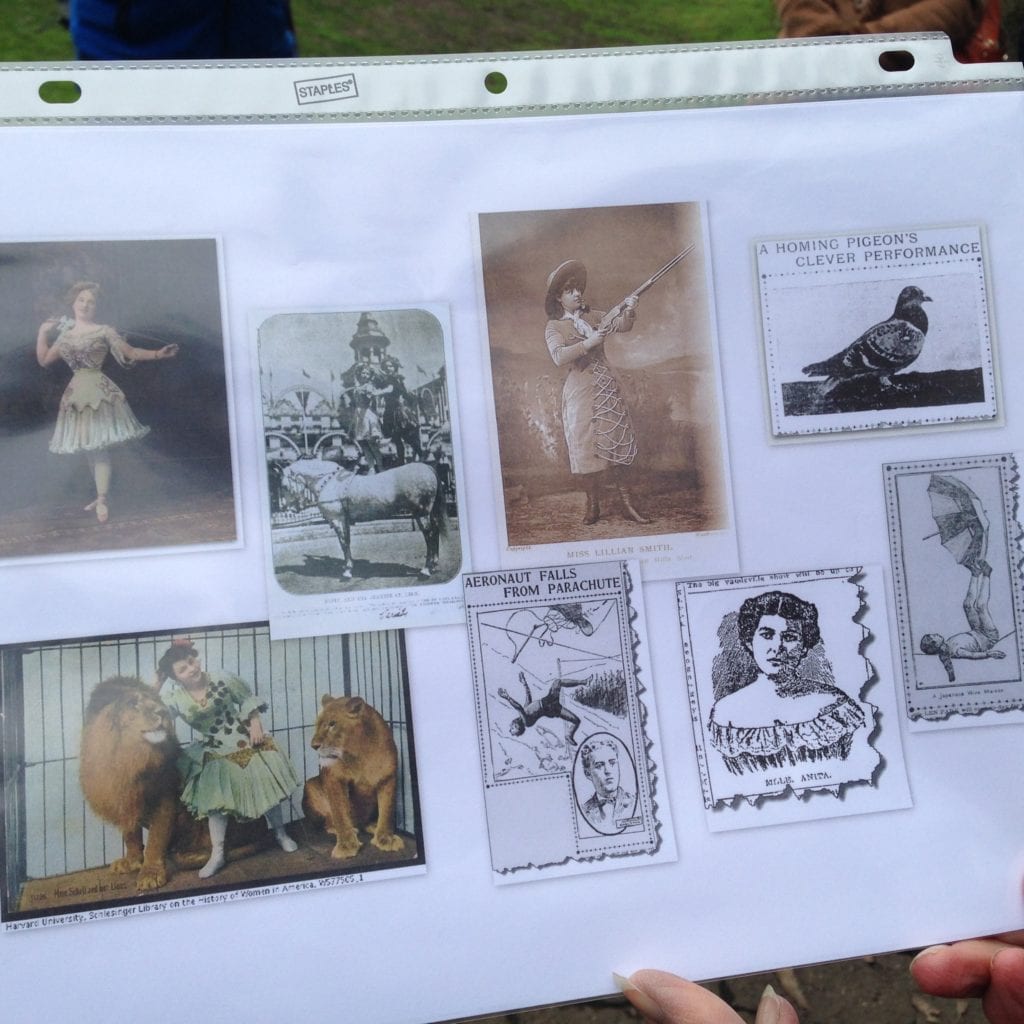

Before he sold out in 1903, Baldwin mounted pavilions that regularly attracted as many as 8,000 to 15,000 people with a perfect storm of popular entertainment featuring bareback horse riders, lion tamers, aeronauts leaping from air balloons, trained homing pigeons, and even a female sharpshooter named Lillian Smith, a doppelganger for Annie Oakley. Baldwin’s vaudeville acts boasted wrestling matches and prize fights, and in the aftermath of the 1898 Spanish American War, the 4th Cavalry Mounted Band from the Presidio, the last mounted band in the U.S. Army, tooted their instruments where the canyon baseball diamond and soccer field now stand.

“By early 1900s things began to peter out,” said Rose. “Baldwin found his Chenery Street lots not selling. Buyers didn’t want to look out their front windows and see throngs of people traipsing by to get to his zoo.”

After Baldwin sold out in 1903, the Crocker Estates took over management and the canyon continued to be a popular destination for private parties that required reservations. The City bought the land in 1922 and it reopened to the public.

On her last lap now, heading for the homestretch, Rose and her group moved along a path paralleling the Islais Creek, a trail Glenridge nursery children dub “Banana Slug Way.” Way off, on the eastern side of Alms Road, above what the Recreation and Park Department calls the Angelica Rocks, stood a group of Berkeley Way homes, one of which had been set ablaze on June 2, 2011, resulting in the death of two City firefighters, Vincent A. Perez and Anthony M. Valerio.

Rose pointed across the creek, ready to bring down the final curtain on her epic.

“Over there, along the fire road, California wanted to construct a freeway,” she said, eliciting a chorus of audible groans from the antiquarians. Each tried to wrap their minds around a Nimitz or Embarcadero-style freeway envisioned by traffic engineers. The elevated roadway would have bisected Glen Canyon, cresting at Portola Drive then tunneling under Portola for 1,100 feet, emerging along Laguna Honda/7th Avenue through Golden Gate Park to Park Presidio Boulevard before reaching the Golden Gate Bridge.

“The Gum Tree Girls — Geri Arkush, Zoeanne Nordstrom and Joan Seiwald — battled the Department of Public Works first over widening Bosworth in the 1960s,” Rose said, “and then the California Highway Department over the freeway.”

Geri Arkush has passed away, but surviving freeway foils Nordstrom and Seiwald are often seen together walking the canyon Gum Tree Girls Trail, which honors the trio who stood shoulder-to-shoulder and said – “Enough. Not Here.”

Back at the canyon entrance, Rose apologized for being a half hour late, but she’d forewarned the group this might be so if there were an inordinate number of questions.

Sally Ross, who lives in the Sunnyside, made ready to depart. She’d walked over to the canyon, and now she tugged a knit cap over her ears, keeping the afternoon chill at bay.

“Evelyn’s walk was most enjoyable, showing actual places where events took place,” she volunteered. “It made information ever more meaningful, making the canyon’s history something that can be enjoyed and passed along to others.”

That Evelyn Rose most certainly did.

To learn more about the Glen Park Neighborhood History Project and future neighborhood walks go to www.GlenParkHistory.org.