Over the past several years, we have uncovered many impressive histories connected with Glen Park. One not yet discussed is the Glen Park connection to the glamor and glitz of Hollywood that began during the earliest days of Tinseltown. This post is Part 4 of 5 (see Part 1, The Glen Park Glenodeon, Part 2, Bob Lippert, King of the B’s, and Part 3, Glen Park Aeronaut on the Big Screen.)

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Margot Patterson Doss, in her popular column San Francisco at Your Feet, described Glen Canyon in 1963 as: “…a singularly beautiful arroyo, a secluded narrow valley with a small stream rippling through it, a morsel of our Western wilderness heritage…From behind the rugged rocky outcropping, strains of ‘Empty Saddles in the Old Corral’ are discernible.” In a similar article nine years later, Doss again describes Glen Canyon: “The Children’s Walk par excellence in San Francisco leads out of the Old West by way of Shane, Zane Gray, and the back lot…through chaparral…Legends lurk ’round every rock. So do the bad guys and the good. Who knows what desperado waits to cut us off at the pass?”

To have been a child growing up along the slopes of Glen Canyon in the early decades of the 20th century must have been a magical experience; before the serpentine O’Shaughnessy Boulevard bisected the southern and western slopes and when the path from Sunnyside to the summit of Mt. Davidson was interrupted only by native wildflowers. Games of Cowboy and Desperado are easy to imagine. One Glen Park lad who, according to his youngest brother had played such games, would grow up to become a real-life Hollywood cowboy.

His father, Olaf Ludvig Lee, emigrated from Norway to the United States in 1907. A house carpenter by trade and living on Noe Street near Duboce Park, he was employed at the Presidio of San Francisco when World War I broke out. After enlisting as a private in Company C of the US Army 115th Engineers in 1918, Olaf saw action in the Loire Valley, France. When he returned in July 1919, his military service led to automatic naturalization. In 1924, Olaf married Norway native Emma Andrea Hammer in San Francisco and according to Lee family history, built his home on Nordhoff Street in 1927 on Glen Park’s Martha Hill with his own hands. The Lees would have five sons – Lloyd, Palmer, Robert, Gilbert, and Melvin – all of whom likely spent a lot of time playing among the rocky slopes of Glen Canyon just down the hill.

Lloyd, the eldest boy, would make his own notable history. Just as Glen Park’s Dan Maloney had done in 1905, Lieutenant Lloyd Arthur Lee made aviation history when he piloted a B-29 Superfortress to a new height record of 42,780 feet over Guam in 1946. After graduating from the University of California at Berkeley with a degree in civil engineering, Lloyd worked on major projects including the supervision of renovations to the Hoover Dam, construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) Transbay Tube between San Francisco and Oakland, and the rebuilding of the State Capital Building in Sacramento.

But it would be second-eldest son, Palmer Edvind Lee, who would grow up to become a Hollywood cowboy. Born in San Francisco in 1927, in later years Palmer would grow into an imposing figure standing at 6’4” and weighing in at nearly 300 pounds. After graduating from Lowell High School, Palmer enlisted as a private in the US Army Air Corps. During World War II, he was assigned as a cryptographer intercepting and decoding enemy messages in the South Pacific. He was discharged with the rank of sergeant in 1946.

Palmer’s show business career began when his buddies dared him to audition for a radio spot at KNBC when it transitioned from KPO-San Francisco. His deep voice helped him win the spot and soon after he was an announcer at KEEN in San Jose. Hollywood also made note of his voice, helping him land his first film role (uncredited) as an ambulance driver in My Friend Irma Goes West with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis (1950). By 1951, Palmer had been signed as a contract player with Universal Pictures. One of his first movies at Universal was Francis Goes to West Point (that would be Francis the Talking Mule, a very popular mid-century series of seven movies), starring Donald O’Connor and a very young Leonard Nimoy in an uncredited role.

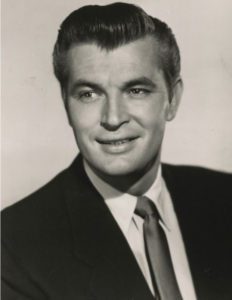

By 1953, Palmer had already appeared in about a dozen films. Yet, his performance in The All-American starring Tony Curtis (1953) earned him a new stage name. Universal decided Palmer Lee “wasn’t good enough for a star personality.” So, they dubbed him Gregg Palmer. He would later share he wished he had kept his legal name: “It didn’t hurt Humphrey Bogart or Arnold Schwarzenegger…I think Universal was going for a heavy sound, like ‘Tab’ or ‘Rock’.” Receiving credit as Gregg Palmer began with his next film, Taza, Son of Cochise (1954) with Rock Hudson and Barbara Rush, and continued for the remainder of his career. His filmography continued to grow with roles in Magnificent Obsession (1954) with Rock Hudson, Jane Wyman, and Agnes Moorehead, and as platoon leader Lieutenant Manning in To Hell and Back with American war hero, Audie Murphy (1955).

Up to this point, Palmer had been involved with only a smattering of Westerns. After being snubbed by Universal Pictures for further talent development as they began hiring major stars from other studios, he became a freelancer and soon landed a role on the television Western series, Stories of the Century: Jack Slade (1955). Afterwards, the bulk of his career would be found in Hollywood cowboy-dom. By the end of the 1950s, he had appeared in several television Westerns whose names today are mostly forgotten. But in the 1960s, his popularity as a supporting actor took off, appearing in such classics as Wagon Train (NBC), Have Gun – Will Travel (CBS), The Big Valley (ABC, with Barbara Stanwyck), Rawhide (CBS, with Clint Eastwood), and appearing 13 times in Death Valley Days (NBC, then syndicated), 9 times on The Virginian (NBC, with James Drury), and 5 times on Bonanza (NBC, with Lorne Greene, Pernell Roberts, Dan Blocker, and Michael Landon). But it would be the ever-popular Gunsmoke (CBS) where Palmer would make the most reappearances – 21 times, in fact – the second most of any actor during the 20 years the beloved Western remained on the air. His frequent appearances were in part due to his physical stature: Marshall Dillon, played by James Arness, stood at 6’7” and when the two stood side by side, Palmer was not dwarfed by Arness’ superimposing figure.

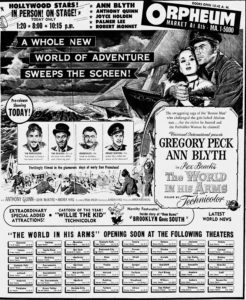

By the late 1960s, Palmer had established himself as the consummate desperado. His burly physique and often grizzled appearance also appear to have been key in leading him to what would become some of his most memorable cowboy movie performances. A decade earlier, Palmer had been introduced to John Wayne by actress Ann Blyth, whose breakout role was playing Joan Crawford’s daughter in Mildred Pierce (1945). Wayne had formed The John Wayne Stock Company in 1945 because he wanted to work with friends who also happened to be character actors (including Ward Bond and Paul Fix), and who he knew could always be depended on to perform well. John Wayne was likely familiar with the Bad Guy persona Palmer had been portraying on nearly every television Western and invited him to appear in The Comancheros in 1961.

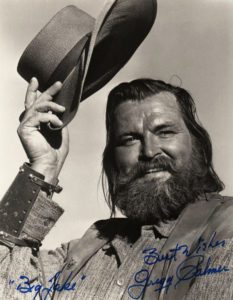

While Palmer and Wayne did not have a scene together in The Comancheros, the “Duke” gave Palmer the nickname of “Grizzly” and added him to his stock company. For five additional films, Wayne would request his staff to, “Get me Grizzly.” Palmer went on to appear with Wayne in The Undefeated (1969), Rio Lobo (1970), and Chisum (1970). In between scenes on set, Palmer and Wayne would often play chess together.

What would be considered Palmer’s best and perhaps most memorable performance with Wayne (and his career) was his portrayal of a machete-wielding desperado named John Goodfellow in Big Jake (1971). One frightening scene in the movie would make Palmer notoriously famous in cowboy fandom, leading him to become known as “the man who killed John Wayne’s dog.” Palmer later commented, “Folks tend to remember those things.” He also appeared in Wayne’s last film, The Shootist (1976); the two men meet in the opening frame as a highway robbery goes very wrong for Palmer’s character.

Gregg Palmer’s final role was in the television miniseries, The Blue and the Grey, in 1982. In his final years, Palmer became an avid golfer. He also attended Hollywood cowboy conventions, including The Golden Boots Awards, though he never won the award himself. In 2014, he was a guest speaker at a John Wayne birthday celebration at the Autry Museum of the American West. In this video from the event, he shares his memories of Wayne along with highlights of his own career and growing up in San Francisco.

You can view Palmer’s filmography at the Internet Movie Database (imdb). While he may have been known as Grizzly, in real-life Palmer Edvind Lee, aka Gregg Palmer, was a warm and comedic human being, the antithesis of his frequently ruthless onscreen roles. He was 88 years old at the time of his passing on October 31, 2015, in Encino, California. He was buried at Olivet Cemetery in Colma. Palmer succeeded in leaving behind a legacy of desperado portrayals, both as an adult in Hollywood and as a youngster in Glen Canyon.

In the final post, Part 5, a former student of Fairmount Grammar School (today, Dolores Huerta Elementary School) becomes a 1960’s television icon.

Evelyn Rose, Director and Founder of the Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project, is documenting the histories of Glen Park and nearby neighborhoods. To learn more about our local histories, visit www.GlenParkHistory.org. The Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project is currently offering intermittent virtual programs during the ongoing health crisis. Join the mailing list: GlenParkHistory@gmail.com. The Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project is fiscally sponsored by Independent Arts & Media, a California non-profit corporation. Evelyn is also the author of the history website, Tramps of San Francisco.