Over the past several years, we have uncovered many impressive histories connected with Glen Park. One not yet discussed is the Glen Park connection to the glamor and glitz of Hollywood that began during the earliest days of Tinseltown. This post is Part 3 of 5 (see Part 1, The Glen Park Glenodeon, and Part 2, Bob Lippert, King of the B’s.

The successful lunar programs of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have been portrayed in such movies as The Right Stuff (1983), Apollo 13 (1995), and Hidden Figures (2016). But did you know that our district has its own “hidden figure,” dating back to the earliest days of flight? Twenty-one-year-old Daniel John Maloney was a boarder in the home of a French laundress on Palmer Street (today Whitney Street) in Fairmount Heights when he listed his occupation as “aeronaut” in the 1900 United States Federal Census. His chosen career, one that can only be referred to as a Victorian extreme sport, had been launched a year earlier while working as a groundskeeper at the Glen Park and Mission Zoo in Glen Canyon.

Aeronauts were daredevil performers who swung and twirled on a trapeze while suspended from a hot air balloon hundreds of feet in the air before parachuting back to terra firma. In 1879, former circus performer Thomas S. Baldwin had been the first person to dangle from a trapeze attached to a hot air balloon. He is also credited with the first parachute descent in the United States, a feat he performed in 1887 by jumping from the gondola of a hot air balloon suspended over Golden Gate Park. Soon after, Baldwin would add the parachute drop to his aeronautic trapeze act and by the 1890’s, this death-defying act were being performed across the United States.

Glen Park and the Mission Zoo was famous for its vaudeville performances and daredevil displays. One Sunday in the fall of 1899, an aeronaut who was scheduled to perform failed to show. Despite having never left the ground before, Dan Maloney volunteered to take his place and go aloft. Soon, the “Daring Dan Maloney” had made several ascents at Glen Park, a few with rocky landings, including the last one in which he was badly injured. While he never performed again at the Glen Park pleasure grounds, he continued his aeronautic career up and down the Pacific coast, sometimes using the moniker “Professor LaSalle.”

By 1904, Maloney had become the “test pilot” for local aviation pioneer, Professor John J. Montgomery of Santa Clara College (today, Santa Clara University). A graduate of San Francisco’s St. Ignatius College (today, St. Ignatius Preparatory College), Montgomery in 1883 had been the first human to achieve sustained, heavier-than-air flight. Soaring in a fixed-wing glider of his own design, his success preceded the Wright Brothers achievement of powered flight by 20 years.

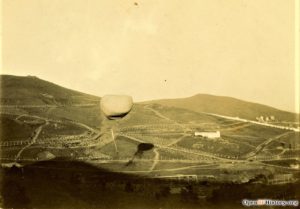

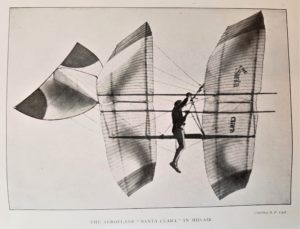

When Montgomery and Maloney became research partners, Montgomery was working to perfect a heavier-than-air, fixed-wing craft that would not only soar but also for the first time maintain both equilibrium and control. With Maloney sitting on a bicycle seat and maneuvering primitive hand and foot controls, Montgomery’s craft, The Santa Clara, was test flown successfully over the Santa Cruz Mountains in March 1905. This triumph was followed by a repeat, public performance in April at Santa Clara College. With Dan Maloney astride The Santa Clara, the craft was lifted aloft by a hot air balloon (a suggestion provided by Thomas S. Baldwin) and cut loose at an altitude of 4,000 feet. A safe, on-target landing about 15 minutes later at Santa Clara College made Dan Maloney the first human to soar at high altitude in a heavier-than-air, fixed-wing craft with equilibrium and control.

Sadly, Maloney would be killed in a crash of The Santa Clara just three months later. In 1909, Montgomery would suffer the same fate in San Jose while personally testing his newer craft, The Evergreen. Both men for years were generally omitted from American aviation history, essentially having been written out by the Wright Brothers (who, by the way, had surreptitiously incorporated some of Montgomery’s key innovations without any notes of attribution with the assistance of a Chicago aviation researcher Octave Chanute).

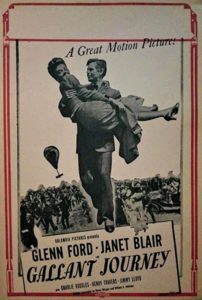

Finally, in 1946, overdue recognition arrived with the release of Gallant Journey by Columbia Pictures. Premiering in San Diego near Montgomery’s first successful flight in 1883, directed by William A. Wellman, and starring Glenn Ford as John J. Montgomery, Janet Blair as his wife, Regina, and Jimmy Lloyd as Dan Mahoney (not Maloney), the movie follows Montgomery’s career until his tragic death. Director Wellman was an experienced aviator who had flown for the French Foreign Legion in World War I and later served as an Army Air Corps instructor. His movie, Wings, won the first Academy Award for Best Picture in 1927.

Wellman used great attention-to-detail in the re-enactment of Maloney’s first public high-altitude flight. Using Montgomery’s archived design plans, he reconstructed the 42-pound Santa Clara to exquisite detail while adding a few modern safety standards. With an experienced pilot at the controls, the replica was taken aloft by hot air balloon where it soared at high altitude, just as the real Dan Maloney had done in 1905. Even Mahoney’s bedazzling in-flight tights are nearly the same as seen in original images of the event.

The cinematographer for Gallant Journey was Burnett Guffey, with aerial photography by Elmer Dyer. As the Santa Clara region had changed significantly over the previous 40 years, flight scenes were filmed over Del Monte, California. According to David Sterritt of Turner Classic Movies, “The most impressive element of Gallant Journey is its camerawork, which captures the exhilaration of gliding above the California countryside in grandly picturesque images. To get these, producer-director Wellman employed multiple cinematographers, and it’s a pity he (or Columbia Pictures, his studio) didn’t choose to shoot it in color, which could have raised a diverting movie to the level of an enchanting one.”

While Gallant Journey is not widely distributed, you can view a clip of Maloney’s re-enacted, first public high-altitude flight at Turner Classic Movies. While Maloney’s death preceded the first display of Hollywood lights by several years, the accomplishments of the young lad from Fairmount Heights and Glen Park are now part of Hollywood history.

In Part 4, a boy from Nordhoff Street on Glen Park’s Martha Hill grows up to become a real-life Hollywood cowboy.

Evelyn Rose, Director and Founder of the Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project, is documenting the histories of Glen Park and nearby neighborhoods. To learn more about our local histories, visit www.GlenParkHistory.org. The Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project is currently offering intermittent virtual programs during the ongoing health crisis. Join the mailing list: GlenParkHistory@gmail.com. The Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project is fiscally sponsored by Independent Arts & Media, a California non-profit corporation. Evelyn is also the author of the history website, Tramps of San Francisco.