To celebrate the Glen Park Association Website turning ten years old, we are reposting some of our favorite stories from the last ten years.

Hank Greenwald sat at Destination Bakery, nursing a cup of hot chocolate, reminiscing about a broadcast career that witnessed him announce 2,798 consecutive San Francisco Giants games before he retired in 1996.

Despite the chilly January weather outside, the Chenery Street confectionery invited bright sunshine through its western-facing window.

“I was 10 years old in 1945 when I saw Hank Greenberg play his first game after returning from the Second World War,” said Greenwald, who has lived in Diamond Heights since 1978, but was born in Detroit, Michigan. “My parents named me Howard and it became “Howie,” which I never liked.”

“So I changed it to Hank,” said Greenwald, renaming himself after the Jewish slugger who’d just returned to civilian life after serving in the Army-Air Corps.

Earlier that afternoon Greenwald was driven down Elk Street by his son Doug who, following in his father’s legendary footsteps, announces minor league Fresno Grizzlies baseball games.

The younger Greenwald pulled into the Glen Canyon Park turn out and Hank Greenwald alighted.

With the help of a cane, fashioned after a Louisville Slugger bat, Greenwald took halting steps toward the baseball diamond’s pitcher’s mound. Hobbled by recent medical conditions, the 81-year old cautiously avoided divots in the outfield turf.

Greenwald may have slowed down a bit, but his mind remains sharp as a tack, his wit even sharper.

“I burned ‘Hank Greenwald’ onto the bat,” he said, waving his baseball pine, “in case I forget my name.”

Standing a few feet from where a shortstop and a second baseman make routine double plays at the keystone corner, Greenwald remembered Glen Park from nearly 40 years ago.

“Doug played ball on this field and my wife and I sent him to Silver Tree summer camp,” he said. “On Diamond Street, on the way to Candlestick, I’d stop and buy doughnuts. Charlie and Judy Creighton were part of our baby sitting co-op.”

Backtracking to Elk Street, he continued.

“I buy and sell books at Bird & Beckett and enjoy its Friday night jams,” he said.

With a twinkle in his eye, he continued. “My wife is happy anytime I can clear out my nest of books.”

Later, at Destination Bakery, he elaborated.

“As a baseball announcer on the road, there’s a lot of down time and I’d haunt bookstores,” he said, “Cincinnati and New York had especially good ones, and they’d help me get through the season. You have to keep your mind fresh. Sometimes before a series I’d hop a train and go as far as I could. Get away from it. Come back ready to get behind the mic.”

Greenwald’s favorite baseball book remains Lawrence Ritter’s The Glory of Their Times.

“It perfectly captured baseball in the 1920s,” he said. “The ballplayers reminisced about their days on the diamond.”

“I received a nice letter from Ritter,” he volunteered, continuing his literary rift, “I once had an opportunity to interview The New Yorker’s Roger Angell for City Arts and Lectures.”

Three years after retirement, Greenwald turned his attention to the written word himself, penning a 1999 memoir, The Copyrighted Broadcast.

Hank Greenwald sat behind a KNBR microphone from 1979 to 1985 before taking a two-year hiatus to broadcast New York Yankees games. In 1989, a memorable year for the hometown nine, he returned to Candlestick Park from the Bronx, remaining in the Giants announcer’s booth until 1996.

“I returned to the Giants just in time for the earthquake and their second World Series since arriving to the city in 1958,” he said. “Ron Fairly was doing the pre-game that October night, and I was standing in the press box with Duane Kuiper. Things began to shake back and forth. The press box seemed to be heading for home plate.”

He paused for effect, taking a sip of his cooling hot chocolate, toying with a 1989 World Series ring that adorned a ring finger.

“Ninety-five percent of the fans were from the Bay Area. They didn’t panic. Ninety-five percent of the press weren’t from here and they jumped over each other for the closest exit.”

Candlestick Park was something special, Greenwald believes. Especially for celebrated free agents in the hunt for salary hikes.

“San Franciscans didn’t grow up with warm summers,” Greenwald said. “To them the weather didn’t matter. But I think it hurt the Giants. Other ballplayers didn’t want to be traded or sign here. The wind played havoc with fly balls and blew papers into their eyes.”

An only child, Greenwald’s father worked as an executive for Neisner Brothers, an East Coast Woolworth-type five and dime.

“My dad was transferred to Detroit where he remained until I was ten years old. Then he returned to Rochester, NY. For me, it was like going from the major to the minor leagues.”

Continuing, “In the sixth grade the school district obtained tickets for kids to attend Rochester Redwings games. We were called the “Knot Hole Gang.” This was the year I saw Jackie Robinson play, making history with the Montreal Royals.”

Greenwald played organized baseball, but only in high school. Playing might be gilding the lily, he’d be the first to concede.

“I rode the bench,” he said, another smile creasing his lips. “There was no need for a 5’6” first baseman. I announced school basketball games instead, and the principal let me do a five-minute Friday morning sport broadcast over the PA system.”

Graduating high school in 1953, Greenwald enrolled at Syracuse University where he bundled his love of baseball and basketball with broadcasting, a passion that has never abandoned him.

“Syracuse had a wonderful broadcasting program, and I majored in radio and television,” he said. “Cleveland Browns great Jim Brown was a classmate, and working for the university radio station I did baseball and basketball.”

Upon graduation in 1957, he landed a job at WWBZ a 5,000 watt AM station in Vineland, New Jersey.

“I was the morning guy, working the six-to nine drive time slot,” he said, “I’d return at twelve and stayed on the air until 3 P.M.”

“At noon I read the egg prices,” he said, enjoying himself. “For this the station paid me $65.

Across the country, around the same time, Candlestick Park’s Gulden’s mustard was going for the princely sum of $.25 a jar at the local Safeway, so stretching $65 a month wasn’t all that difficult.

“It paid the rent, if eating wasn’t a high priority,” Greenwald laughed.

Working for WWVV had perks, though. The Philadelphia Phillies sent him ducats and he’d drive to Philly and take in games. Big Five basketball hoops, too. In the fall of 1959, Syracuse’s WOLF AM hired him to do news and sports.

“From 1960-64, I did play-by-play for Syracuse football,” he said. “These were the years of Ernie Davis, John Mackey, Floyd Little and Larry Csonka.”

Throughout these early years Greenwald never strayed far from his Syracuse University lecture halls, eventually parleying academia’s lessons into his memorable years as a Giants announcer.

“Larry Meyers, my university professor, told us ‘root with your heart, not with your mouth,’ and ‘the great play is not dependent on the team who makes it,’” Greenwald said. “It’s more important that broadcasters create baseball fans, not Giants or Warriors fans.”

“I never had a home run call; I never wanted to get locked in” he volunteered. “Besides, not every home run is that exciting.”

“Lindsey Nelson, my broadcast partner, told me ‘don’t ever get caught up with wins and loses. If you do, and you’re announcing a bad team, you’ll sound like they play.’”

“Always prepare yourself every day for the worst game,” he added, sealing his case.

Never tagged with the moniker “homer,” Greenwald was known for both his professional objectivity and preparation, hefting brief cases full of statistics and anecdotes into the broadcast booth to enrich his hours on the air.

“People invite us into their homes when they turn on their radios, and radio calls on our skills as broadcaster,” he said. “Radio is unique, it becomes part of our family, it’s all the listener has and we use it to create descriptive word pictures.”

Giants, A’s and 49ers broadcaster Lon Simmons, a Greenwald contemporary, nailed it when asked what one factor made him a Cooperstown Hall of Fame announcer.

“I was a college English major,” Simmons said.

In his turn, Greenwald echoed Simmons, “I became a story teller.”

Hank Greenwald eventually arrived in San Francisco in 1964, working courtside with Bill King, a 2016 Cooperstown inductee, announcing NBA Warriors games. He made a stop in Hawaii to call PCL Hawaii Islanders games, even taking a detour to Australia for a few years, which is where his son Doug was born. In 1976, KNBR hired him to do Sports Phone 68 and from there he segued to his very first inning as a Giants broadcaster.

Along the journey he shared the mic with Lindsey Nelson, David Glass, Phil Stone, Ted Robinson, Gary Park, Duane Kuiper, Mike Krukow and Ron Fairly.

“Fairly, a former Los Angeles Dodger first baseman, would get emotional about baseball and its significance,” said Greenwald. “Ron knew it was a generational game.”

A game knit tightly into the American quilt, a game about continuity, despite changes such as free agency, the designated hitter, instant replay, pitch counts, and an exhibition All Star Game determining which team obtains home field advantage in the World Series.

Nudged to come up with his favorite baseball film, Greenwald doesn’t hesitate.

“Field of Dreams,” he said, thinking of the last scene in the Kevin Costner movie. “I occasionally played catch with my dad, but it was my parents interest in the game that got me going to Detroit’s Briggs Stadium.”

All these years later, he’s stayed in touch.

“I’m given a seat,” he quipped, “in the assisted living section of the AT&T press box.”

It’d been two hours since he’d leaned over his hot chocolate.

Across the street, Bird & Beckett beckoned. Down the block he could see Le P’tit Laurent where he and his wife, Carla, sometime dine.

Crossing the street, Greenwald volunteered, “Dolph Camilli lived in Glen Park, you know.”

In 1941, Camilli won the National League MVP award with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Overshadowed by Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio, Camilli, a Sacred Heart High School graduate, didn’t end his signature season batting 406 or hitting in 56 consecutive baseball games like the two American Leaguers had.

Camilli, the one-time San Francisco Seals, never explained or complained, but simply said:

“I’d have played even if they just given me room and board.”

It wouldn’t be a stretch to hear Greenwald utter a similar sentiment.

“I loved what I was doing,” he said, entering Bird & Beckett. “I was the luckiest guy in the world.”

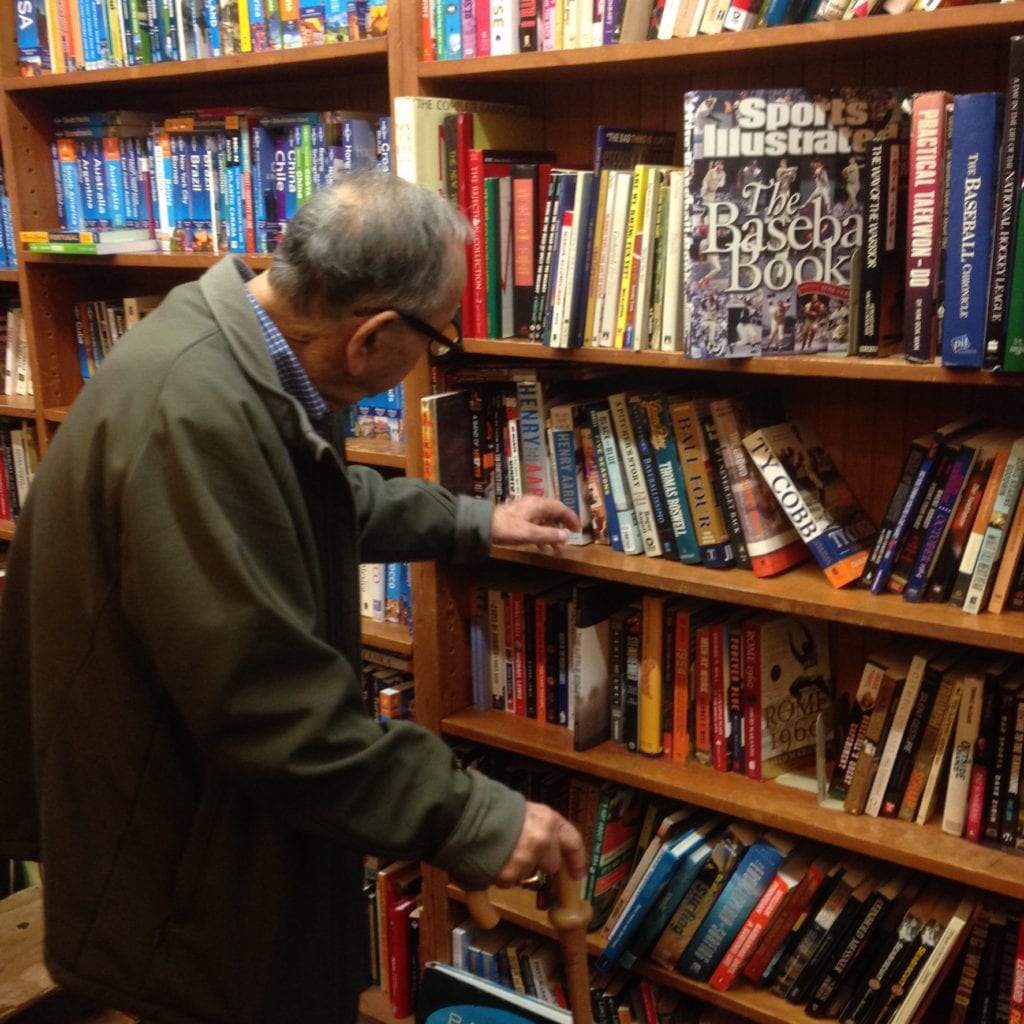

Greenwald closed the store door behind him. He made a beeline for the bookshelf stocked with sports books. He began rifling through the baseball paperbacks, passing over one on Ty Cobb and another one on the 1954 season, the season Willie Mays made his iconic over-the-shoulder, behind-the-back catch of Vic Wertz’s fly ball at the Polo Grounds.

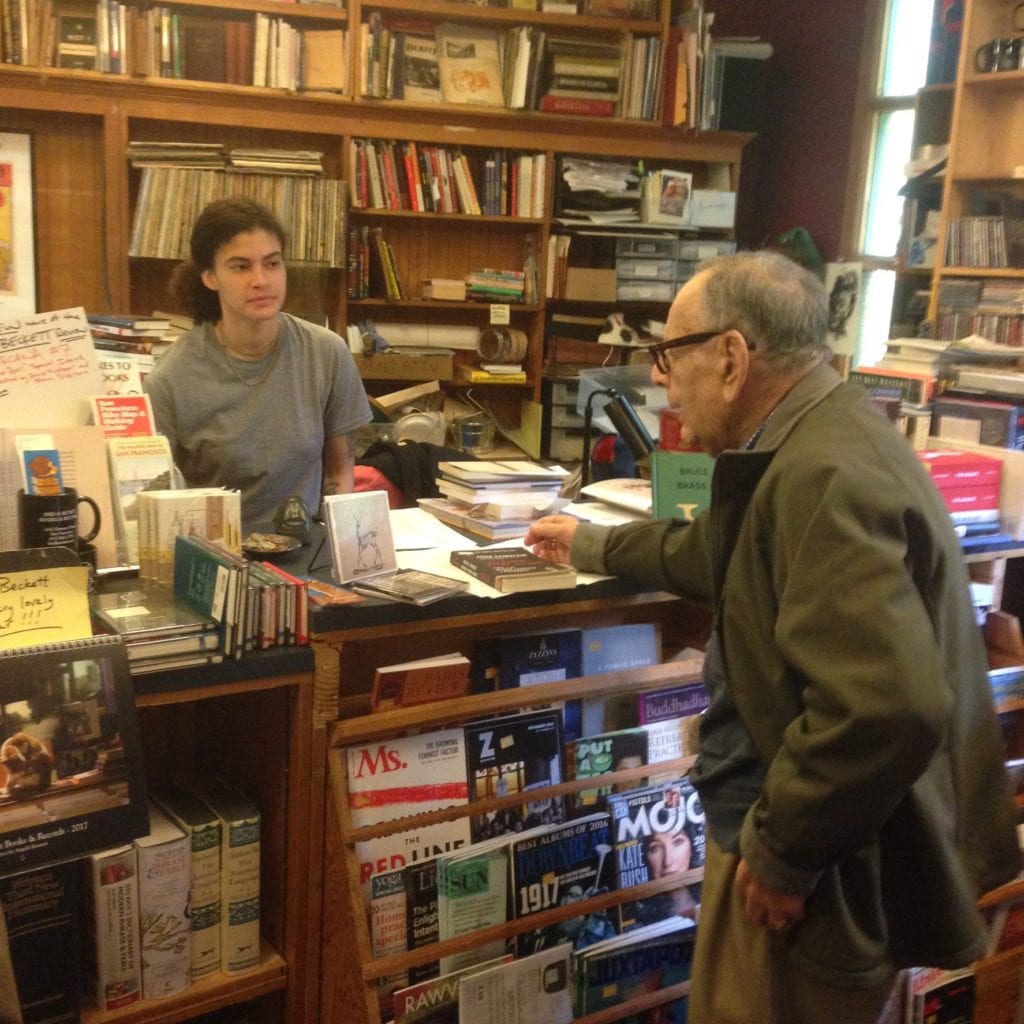

He fingered John Feinstein’s Where Nobody Knows your Name: Life in the Minor Leagues of Baseball. He walked it to the counter, fishing out a twenty-dollar bill. He handed it to Jenna Littlejohn, bookseller Eric Whittington’s clerk.

She tried not to stare.

“My grandfather will really be impressed,” she murmured. “He graduated Mission High School in 1949 and played varsity baseball.”

Outside again, Greenwald clutched his purchase, an account of traversing the minor leagues.

Baseball is a game of reflection, as well as continuity, Greenwald will tell you, capable of authoring a Syracuse University graduate dissertation on the subject.

“As you make your way to the major leagues you meet lots of people along the way,” he said. “Those relationships are special because when you finally make it to the majors you know how far they’ve come and they know the same for you. It’s a special bond: the road buses together, spent hours talking baseball and shared dreams of better days to come.”

The afternoon weather had turned colder. Hank Greenwald balanced himself on his Louisville Slugger and waited for his lift back to Amethyst Way.

It wouldn’t be on a bus, and it wouldn’t be a long journey, unlike the odyssey he’d taken from the bushes to the Big Show, the one his son now travels through California’s central valley.

“It’s tough to walk out of a bookstore,” Greenwald said. “You’re always afraid you’ll miss something.”