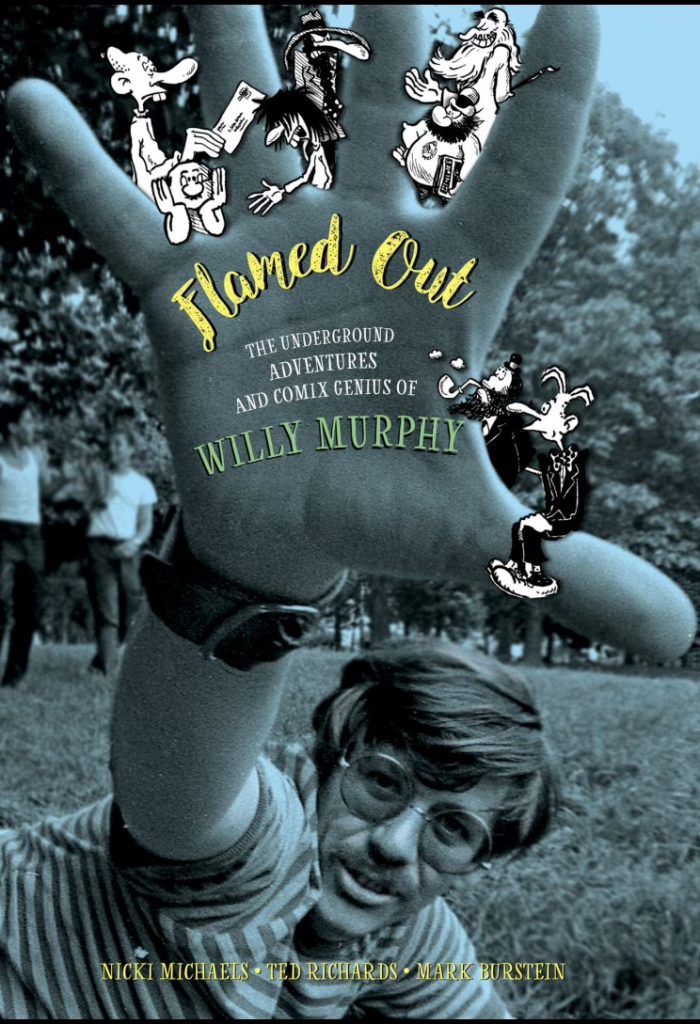

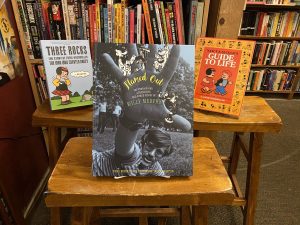

Nicki Michaels, resident of Glen Park since 2007, has been nominated along with two collaborators for an Eisner award, the “Oscar” of comics and graphic novels. There are 32 categories of awards. The trio was nominated in the Best Comics-Related Book category for Flamed Out: The Underground Adventures and Comix Genius of Willy Murphy. (Fantagraphics Underground, 2024. Available at Bird & Beckett Books and Records.)

The award is named for Will Eisner, an American cartoonist, writer, and entrepreneur who died in 2005. Publishers submit nominees to a committee consisting of authors, educators and retailers. Those eligible to vote must be in the industry. Awards will be announced July 26 at the annual Comic-Con 4-day conference in San Diego. Up to 130,000 are expected to attend.

Nicki Michaels was married to Willy Murphy for several years in her early twenties. Now 75, she was born in Manhattan; when she was eight she and her family moved to Port Washington, a Long Island suburb. Craving city life, she ultimately moved back to Manhattan before moving to San Francisco with Willy in 1969. They’d lived together for 1-1/2 years and were married in 1968. After they split up they remained friends until his untimely and sudden death from viral pneumonia in March 1976 at age 39.

Nicki lives on Chenery Street with her husband of 44 years, Nicholas Dewar, and their 16-year old rescue dog, Chubaka, who’s half Pomeranian, half toy poodle. Until December 2022 she was a professionally accredited Life & Wellness Coach.

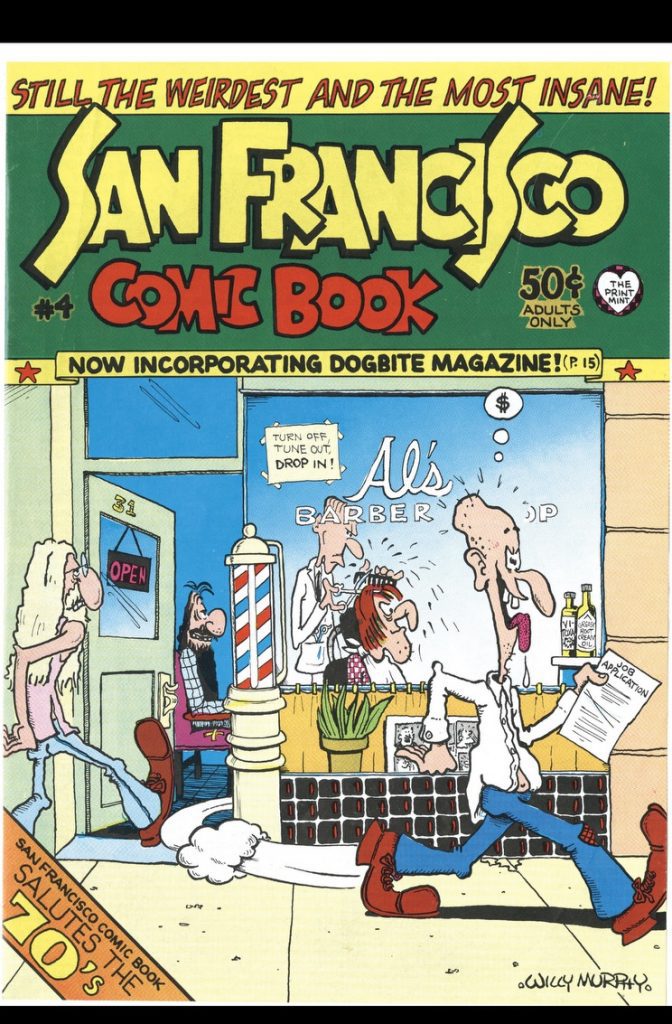

“Comix” is the underground genre of comics that emerged in the heyday of the 60’s. What defines it is that it’s countercultural, politically left, and can be violent and sexual, with dialog that contains a lot of casual profanity and slurs. It’s a way of protesting the mainstream culture and requires a particular mindset to enjoy it without getting offended.

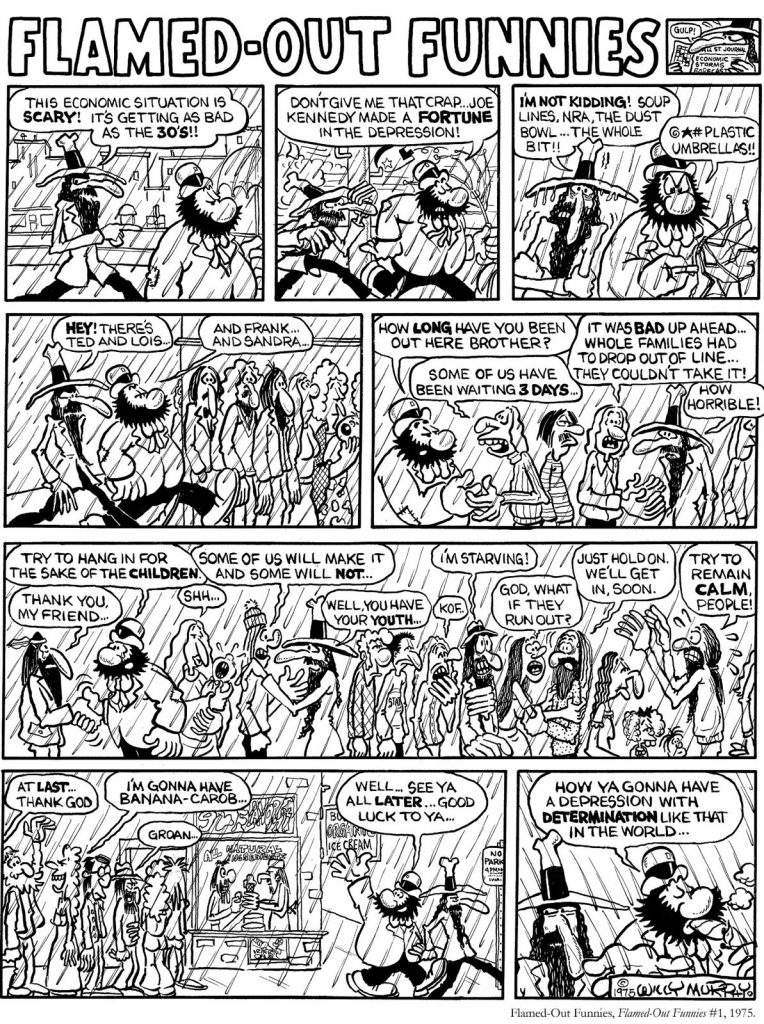

Although Willy used those levers, Nicki describes his sense of humor as gentle, more in the vein of a humorist observation of the human condition. “Even if he was laughing at you, he would make you feel that like he was also laughing with you,” said Nicki. “He would make light of people in different situations but not in a hurtful way. He wasn’t a shock value kind of person and his humor wasn’t like that either.”

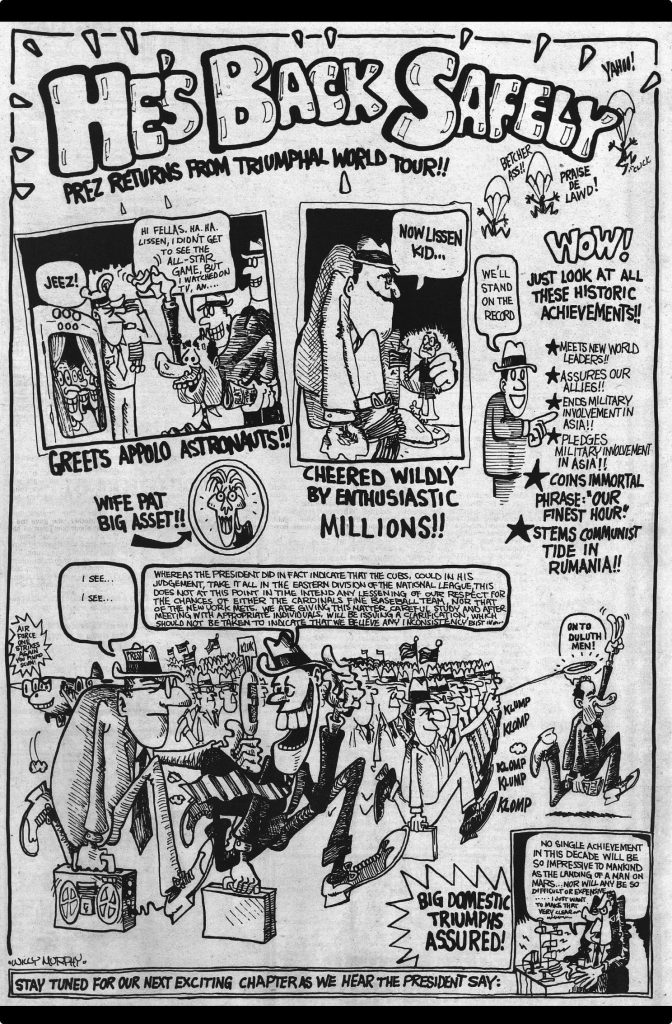

Willy got an undergraduate degree in Fine Arts from the Rhode Island School of Design on the GI Bill as a Navy veteran. He became a well paid advertising executive and copywriter at several prestigious firms in New York City, and also explored photography before pursuing his true passion of cartooning. The words and ideas were always primary, but he perfected his drawing technique as time went on. The first cartoon he had published was of President Johnson on the cover of an underground newspaper, the East Village Other.

Nicki was on board with moving with Willy to San Francisco where the comix scene was gaining traction, with many East Coast comix artists relocating to San Francisco and making it the hub of underground comics.

Much of his political humor was aimed at the disgraced President Nixon and his veep, Spiro T. Agnew. To read Willy’s comix, though, one would think only the names and faces have changed; the farcical politics are the same. Likewise, during this era people were beginning to focus on organic foods. Today that’s but one aspect of the “Wellness” movement.

(Zoom in or stretch for better viewing.)

His work was beginning to appear in anthologies but to make it big you needed to have your own comic book. In those days, comix were self-published so Willy published Flamed Out Funnies in 1976.

He also became known for such comix as Arnold Peck the Human Wreck, Henry Henpeck, Harry Kirschner, The Beasley Boys, and Melody House, among others in various publications.

At the time of his death he was working on a cartoon for the National Lampoon, who’d invited Willy to do a monthly submission. He often became stressed out as deadlines approached. Partying, drugs and smoking wore down his reserves. He was also dealing with his problematic, ailing mother whom he’d relocated from Maine into a local care home. He sent the cartoon off by the Friday deadline and, by the time it arrived in New York on Tuesday, Willy had died.

The book, Flamed Out, had a decades-long incubation period. In 2012, Nicki was still holding on to some of Willy’s things, including sketchbooks and negatives of 65 rolls of film from New York City in the 60’s. “And I thought…when I die, who’s going to get this stuff? I don’t want it to just get tossed out. So I sort of agonized over it.”

She contacted a namesake of Willy’s, Murphy Gigliotti, which brought about a series of events that culminated in the publication of the book 12 years later, including the fact that that Murphy’s father and Willy’s contemporary, Davidson Gigliotti, later called Nicki and convinced her to concentrate on the preservation of Willy’s cartoons rather than his photography.

Ted Richards was Willy’s friend and fellow underground artist and collaborated on Flamed Out and actually was with Willy when he got sick and got him to the hospital when he was about to die. As Willy requested, Ted kept all of Willy’s original artwork in portfolios for all those years, wherever he moved, and it was all in perfect condition.

Nicki and Ted went to the curator of the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco, who wasn’t an expert in the genre of underground cartoons but thought Willy’s cartoons were incredible. But the museum was in the Fisherman’s Wharf area, a tourist magnet, and underground cartoons were not exactly family friendly.

Shortly thereafter the pandemic hit and, there being not much else to do, they made strides on the book and it was finished in spring 2021. But the pandemic had wreaked havoc with the supply chain as it pertained to art books, many of which were printed in China. When that issue was resolved the publisher got a designer and proofs were sent back and forth. (The cover photo was taken by Nicki in Central Park in 1968.)

As the book was nearing completion in the design phase, Ted was experiencing serious health problems–he died before he had a chance to hold the book.

Art Spiegelman, Pulitzer Prize winner for Maus, wrote a blurb for the back cover.

Bill Griffith, a close friend of Willy’s and a contributor to the book, and formerly a Glen Park local now living in Connecticut, is a big name in the comics world and still actively writing. He’s been nominated in three categories. With a long career as a comic book artist, he originated the Zippy the Pinhead comic–a character that would be quite politically incorrect today–that was syndicated in the Noe Valley Voice.

Nicki is thrilled to be nominated even if their book doesn’t win. Willy’s original artwork will soon reside in the Billy Ireland Museum and Library of Comic Art, part of Ohio State University, which is the largest collection in the world of comic book original art and comic books. “To me, this is all about Willy’s legacy. It gives him a higher profile” because he would have been well known if his life had not been cut short.

Justin Green was a very close friend of Willy’s. A fellow underground cartoonist, his work was differentiated by being autobiographical and all about Catholic guilt. At Willy’s funeral he ended his eulogy this way.

“So finally Willy arrives at the last panel. Arnold pries open the lid of the coffin, the cadaver pops up like a jack-in-the-box and slowly ascends with its stage wires slightly visible. The jaws begin to move and in a farewell benediction the spirit of Willy Murphy bids us his last wish:

“For God’s sake, lighten up!”