On a normal day the cul-de-sac at Burnside Avenue off Chenery Street is a hive of activity.

For one thing, it’s the terminus of the Glen Park Greenway, which begins at Brompton Avenue and is frequented by hikers and dog walkers alike. For another thing, there’s the beautiful Burnside Mural right there, a feast for the eyes and the spirit. For yet another thing, there’s St. John Catholic School, where kids, full of energy, can be seen playing and heard shouting from the schoolyard.

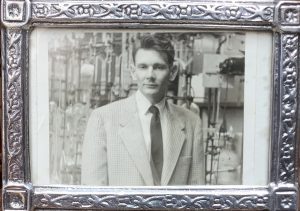

Lastly, there’s the home of Robert (Bob) Seiwald, age 98, and quite possibly the oldest resident in Glen Park, who lives in the green house to the left of the mural. There’s always some project in progress and a parade of family, friends and passersby shooting the breeze.

Bob and wife Joan were married for 66 years. They moved into the two-bedroom house on Burnside Avenue in 1960 and proceeded to raise five children there.

Sixty years ago they were living on Dolores Street, having trouble with their landlord and expecting their third child. They happened upon Glen Park when they came to look at a used dryer machine on Elk Street. They drove down Paradise and a For Sale sign was just going up at the house on Burnside. They bought it on the spot. Joan got a $3,000 loan from her father and they had some money saved so they were able to afford the asking price–a cool $18,500. “These kitchen cabinets cost more than that!” said Bob, pointing to the oak cabinets he had made by a company in the Bayview.

“This was a middle- to lower middle-class neighborhood—people who worked for the city, longshoremen, policemen. There were young families all the way up and down the streets. But overall it’s pretty much the same. They’ve modernized the Rec Center and all that but when we moved here Joan took the children up to the playground everyday and there she met everybody else, including Zoe Nordstrom and Geri Arkush.” (For a story about Geri, scroll in the link to p.21 in the Glen Park Women’s Hall of Fame PDF viewer.)

Their brood of five came quickly, all within seven years.

Bob and Joan had the larger bedroom; the girls had the smaller one. The boys slept in the dining room.

They were able to benefit from a government program at the time, the Federally Assisted Code Enforcement (FACE), which aimed to bring as much of the city up to code as possible by granting low interest loans of 3% to bring properties up to date and even make more improvements.

The loan program allowed them to add a downstairs bedroom for the boys to provide a measure of relief to their bursting home.

In 1970 all of Glen Park was brought up to code, Chenery Street was repaved and street trees were planted.

It was still pretty crowded at home and Joan took the kids to the park to let off steam. Kids also played in the street back then. One thing they did was build coasters (similar to Go Karts) and race down Elk Street onto Paradise Avenue.

Now their children are retired themselves. Jeffrey (born 1957) was an accountant; Scott (1958) was a driver for Loomis and later worked for Bob; Lisa (1960) worked for Levi Strauss as a clothing designer; Christopher (1962) was a computer scientist and software entrepreneur and has six children; Sally (1963) married a Navy lieutenant who died in the first Gulf War and has three children.

Joan passed away very recently, on May 11. She was a neighborhood titan and the last surviving member of the Gum Tree Girls, a trio of housewives who led the so-called Freeway Revolt in the mid-1960s and into 1970, which killed the preposterous idea of a Crosstown Freeway, which would have all but destroyed the Glen Park neighborhood and others in the path of the planned route.

Joan’s last public appearances were at the Gum Tree Girls Festival in Glen Canyon Park and the opening ceremony of the Burnside Mural in 2022. She’d been ill with dementia for over two years prior to her death.

To say the least it’s been a busy life. Early hardships gave way to a successful career and ever- growing family.

Bob’s family was from the Bavaria region of Germany on his father’s side; they settled in Eudora, Kansas. On his mother’s side the family came from Denmark and Norway and settled in northern Wisconsin. They were all farmers. “My grandfather got a job as a school janitor in Denver and that’s where my father and his siblings were born. Ultimately, in 1919 my father and uncle homesteaded 180 acres in northeastern Colorado, of which 80 were arable for raising corn and beans. The rest was sagebrush, sand, cactus, and rattlesnakes. My mother had a homestead nearby.” They were both in their late 30s when they married and 40 when Bob was born in 1925 in Fort Morgan, Colorado.

In the 1920s the family prospered: They had cows and chickens, also a car. “But in 1931 a big storm came and ruined all the crops. The next year it never rained and the Dust Bowl set in, the banks failed and we lost all our money. By 1934 we were destitute.”

Nothing grew and there was no ground cover. The sand was picked up by the winds and carried in clouds. Bob’s father contracted dust pneumonia and died in 1934 when Bob was nine. His mother had a history of breast cancer and had a recurrence in 1935. They went to Wisconsin to be with her family and she died at the end of that year. Bob went back to Colorado to live with extended family.

The trauma took its toll. “I went to high school with kids who’d been together all through school. They took me in for some reason. I didn’t have anyone close to me. When you don’t have any brothers or sisters and no parents, you become distant and it gets very difficult to become close to anybody anymore. It distorts your personality. I was always pretty much a loner.”

Bob got a scholarship to college. He wanted to stay in Colorado to study geology but the schools there were too expensive. In any event, he got drafted in 1944 after he started attending the University of San Francisco.

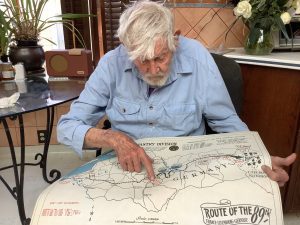

He was in the 89th Infantry Division as a rifleman. “We went across the Atlantic in a huge ship in the wintertime and landed in Normandy in Higgins boats and stayed in Camp Lucky Strike, after which we moved on to Luxembourg and Germany and pursued the Germans toward Poland. At this point for all intents and purposes the war was over. The Germans abandoned tanks, trucks, ammunition. They retreated. No active combat. Humdrum.”

Bob’s unit encountered a concentration camp which was a satellite of Bergen-Belsen with 6,000 Jewish prisoners. At first they thought it was a regular prison because of the striped clothing. It was the first camp liberated by the Allies. They ended up near the Polish border and waited for the Russians but they never came and, in the meantime, the Germans surrendered. “They dumped their stuff and uniforms and headed west along the remains of the Autobahn, melting into the population. We had a stack of German rifles and helmets ten feet high.”

When Bob came back after the war he worked for his cousin in the real estate business. He made enough money to return to USF and finish college with a degree in chemistry.

The GI Bill paid $500 a year for tuition, fees, and books. Bob claims he was “never really all that bright, but I was, in retrospect, clever. I was able to look at things and figure a lot of stuff out. Academically I wasn’t the best of the bunch but in the laboratory, I was the best by far.”

He was awarded a grant to study muscle paralysis. His dissertation at at Webster University in St. Louis was on events at the myoneural junction and curare-like compounds. He synthesized a set of chemicals which resembled curare which cause two kinds of paralysis–flaccid and spastic—but were easy to produce. The chemical was succinylcholine. “For example, it’s used in abdominal operations where they need to relax the muscles. It wasn’t earth-shaking research. We didn’t really learn a lot because the technology wasn’t there.”

Meanwhile, in 1953 Joan graduated from St. Louis University with a degree in Spanish and came to work as a secretary in the chemistry department at Webster University. The head of the department told her he couldn’t pay her much money but he promised her a husband. There were at least 15 or 20 Ph.D. candidates. “For some reason or another, Joan picked me,” Bob mused.

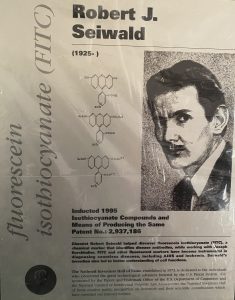

Next, Bob taught at the University of Kansas and did research on tetanus, which up until then could only be seen with an electron microscope. Bob and his colleague Joseph Burckhalter developed the first useful antibody labeling agent, now used for quickly and accurately identifying infectious and other diseases. They published a paper and patented their invention, which also paved the way for the development of other labeling procedures.

In 1995 Bob and Burckhalter were inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame.

In 1957 Bob was offered a professorship to teach organic chemistry at USF, where he remained until his retirement as department chairman in 1989. It didn’t pay well but he had summers off to do research and go camping in Yosemite. Another perk was the children and wives of the faculty got free tuition, so Joan got her teaching credential in English as a Second Language and started teaching in the public schools in 1970.

With Joan’s salary they had some savings and started to buy real estate. Bob had previous experience working in the business after returning from the war. There were a lot of rental properties and the banks and sellers made it easy to get loans.

The first house they bought was on the 800 block of Chenery Street, next a set of flats just over the Daly City line, then ten units on Page Street, and finally, three flats on Guerrero Street in 1982. Once the banks found out Bob was a tenured university professor, they were more than willing to lend him money.

In 1978 they were making enough from their investments to take a vacation in Europe.

The neighborhood saw a large turnover in the early 70s when San Francisco Unified School District began busing students to integrate schools. Many of the Irish, Germans and Italians who were renters in Glen Park, the Mission and Noe Valley moved to the suburbs.

The Seiwalds stayed put but moved the kids to a Catholic school.“We had five children in Glen Park School and they were going to be separated and bussed all over.” One advantage was, if you paid tuition for one child, the rest were free.

Another dynamic affecting Glen Park was Highway 280 going in, causing a lot of upheaval. Many houses in the way of construction were moved to vacant lots in Glen Park.

St. John School, located the Mission and Bosworth Streets area, had to move to accommodate the highway. The archdiocese bought the land and surrounding area and houses where the new school was to be built on Chenery Street and Burnside Avenue. They wanted to buy Bob and Joan’s house and some neighbors’ homes, but prices had gone up and the archdiocese didn’t want to pay enough, according to Bob. Bob and Joan looked at 40 houses but they ended up keeping their home on Burnside.

Somehow Bob found time to be active in the neighborhood. For a time he was president of the Glen Park Property Owners Association, the precursor to the Glen Park Association. There were contentious issues then, as now. Neighborhood organizations had political clout and they banded together to defeat the Crosstown Freeway which would have affected many neighborhoods.

“When I was president of the neighborhood association the meetings were raucous. For one thing, we were dealing with BART. We voted to recommend stations at 30th and Mission and Santa Rosa at Alemany. We found out later that BART had already done the engineering, so it was a ‘feel good’ vote.”

Advanced age hasn’t slowed Bob down too much, nor does he have many health issues. He reports, “It’s harder for me to get up from chairs. I have edema in my foot. Otherwise I’m all right, as far as I know.”

He has a multitude of projects in process. He plans to smooth out the alley with concrete beside his home so moms and nannies can safely push their buggies. He made a panel to add to the Burnside Mural that the artists are going to paint. He has a lava rock garden in front that he’s going to add chert and ferns to. He’s going to plant a big succulent that’s been laying around for several months.

Then there are 50 years of photos and slides to be digitized.

He’s cataloging or disposing of the many minerals he’s collected on travels in Mexico, Europe and South America.

He’s also writing his memoirs. “Pages and pages and pages, and I’m only up to age 30.”

Socially, Bob’s schedule is pretty packed. Once a week he cooks dinner for the ladies across the street. After dinner they have social hour in the living room. His son Jeffrey takes him to Westlake Joe’s once a week. Neighbors and strangers stop by to chat. And Harry, his cat, needs attention.

Photo: Sally Sexton

Bob has taken up cooking in the last few years that Joan was unable to. He tends to look on the bright side of situations. “Organic chemists are good cooks. You synthesize chemicals. If it doesn’t work you take a look at it and figure out what’s wrong and you change the recipe.”

In the next few days, Bob and son Christopher are going on an odyssey. They’re going to retrace Bob’s journey in World War II through Europe.

When asked what he thinks of when he thinks of Joan, Bob says, “I think about her at night when Harry bumps into me and I think it’s Joan in bed. I remember her dying because that’s the most recent thing. I remember our hiking vacations in Italy. I remember cooking for her and feeding her toward the end. Other images from the past, going to the park with the children.”

When asked if there’s anything he wanted to do that he couldn’t because he was so busy, Bob was emphatic. “By and large—No! I was rich. I had a cushy job.”

Reflecting on his long life, Bob is positive. “I lived a spartan life for a long time but the good thing about it, of course is, it got better and better and better from the time we were just about to be Okies until this last couple of years when Joan became ill. It’s been a really good life. We’ve done everything that we wanted to do. You can’t complain. You have to be content with what you get in life. We worked hard at it. You have to be prepared, work at learning how to do everything, look at things and figure things out.”