by Murray Schneider

Emily Bratt still speaks with a trace of an accent from Flatbush, Brooklyn, where she was born 92 years ago.

She has lived in Glen Park since 1950, first settling on Bemis Street when it was nothing more than a dirt path. That move came after she served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps in the final days of World War II, but before she spent 35 years practicing nursing in San Francisco’s Public Health Department and teaching community nursing at St. Luke’s Hospital.

All the while she found time to raise three children with her husband, Thomas Bratt. “I was simply a mother,” she said, sitting in her living room on a summer morning, compartmentalizing memories of the Second World War, as veterans are prone to do.

“It was a terrible war,” she said. “Americans don’t know the half of it.”

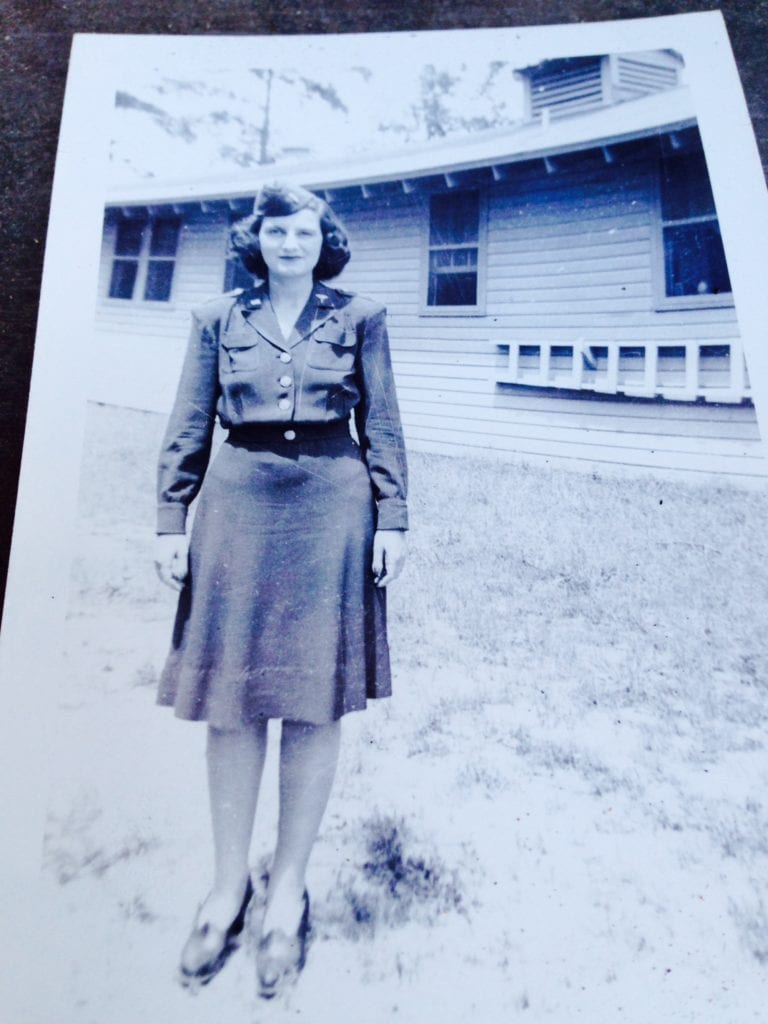

With a brother then serving in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, Bratt graduated from nursing school at New York’s Metropolitan Hospital on Roosevelt Island and enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps. Sent to boot camp at Ft. Dix in New Jersey, she was commissioned a second lieutenant in February 1945.

Patriotic fervor ran high, she recalled. “We were all there to win the war.

“Besides, there were no men around at home,” she added, with a self-deprecating smile, “and Revlon offered women a cosmetic bag and an overcoat if they enlisted.”

Victory in Europe was only three months away, and the United States had begun moving resources to the Pacific, concentrating on defeating Japan. Bratt, however, remained on the East Coast. Assigned to a veterans’ rehabilitation hospital in Atlantic City, N.J., she helped treat seriously injured veterans who were transferred from Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C.

“A big part of my job,” said Bratt, was nursing amputees, sometimes caring for men who’d lost both legs.”

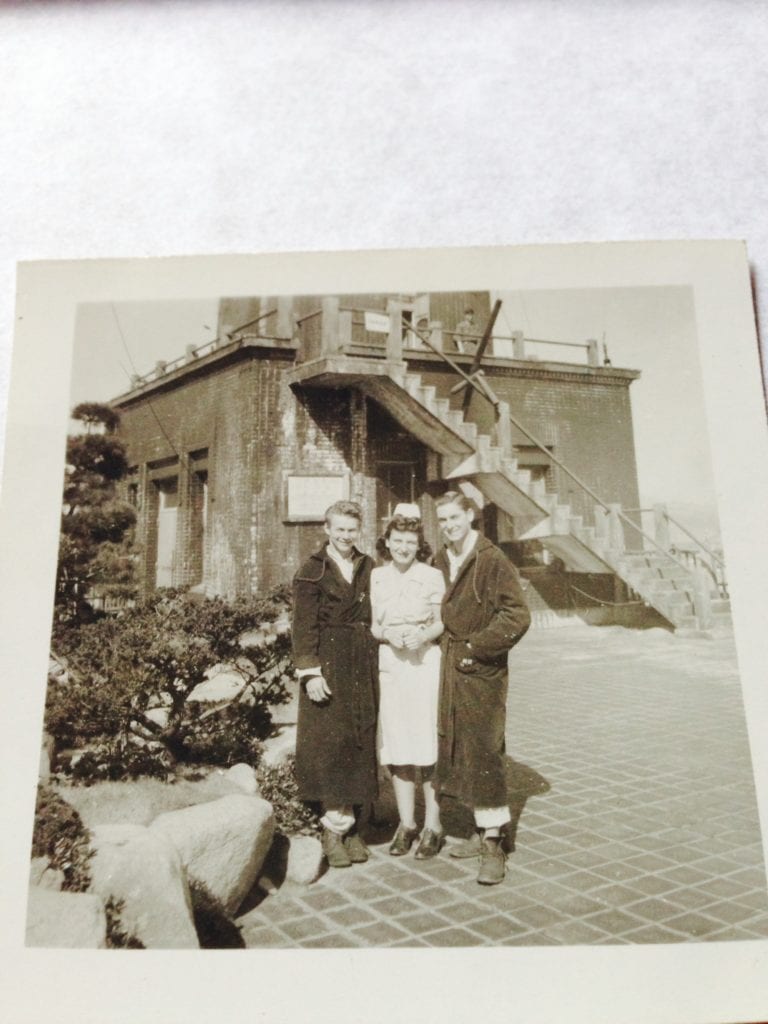

After VJ Day at the end of the war in August 1945, the army shipped Bratt to occupied Korea, where she spent the remainder of her hitch assigned to the American military base in Pusan. The Korean War was still several years away, and the Cold War hadn’t heated up yet.

“We took care of our personnel stationed in Pusan,” she said. “Pretty routine medicine, such as penicillin injections, and the occasional emergency, such as accidental gunshot wounds.”

The nurses were bivouacked in former Japanese barracks, and kept on a short leash, not unlike the “convent-like” atmosphere she had experienced in nursing school.

She mustered out in August 1946. “My brother, Irwin, was discharged in Los Angeles, and he encouraged me to join him. I didn’t like L.A., and came to San Francisco, and briefly lived in a rooming house at Franklin and California streets.”

From the kitchen of her Arbor Street home, where she’s lived since 1953, she gazed out the window upon a large expanse of the Excelsior District. “I met Tom Bratt at San Francisco State in 1948. Then I earned a BA degree in nursing education and later a BS in public heath from UC Berkeley.”

“Tom and I were married on June 10, 1950, just two weeks before the Korean War began.”

Tom Bratt, who won nine Battle Stars on a U.S. Navy destroyer during World War II, was a social worker and carpenter who came from a large Glen Park clan. His father, George, had raised Tom, four brothers and one sister, with his wife, Beb.

Moffitt Street wasn’t a street at all back then, just part of a hillside dotted with wildflowers and buffeted by winds, and the young couple lived in a studio on George Bratt’s property, which backed up on Bemis Street. Their son Tim was born in 1951, followed by Karen in 1953.

When Karen was eight months old, at midnight a few days before Christmas, a runaway car hurtled through the studio and crashed at the foot of the bed, where Karen was asleep in her crib. She was thrown from the crib.

“She wasn’t hurt,” said Bratt. “Tom and I called it our Christmas miracle.”

Another daughter, Holly, was born in 1960. Tom went on to help build much of the Doelger housing in the Westlake neighborhood of Daly City, while Bratt continued her nursing career, which lasted until she retired in 1985.

“I was busy raising a family while teaching community nursing at St. Luke’s,” said Bratt, whose children attended Glen Park Elementary, James Lick Junior High School and Balboa and McAteer high schools.

“Working as a public health nurse, I’d make home visits, providing information about TB and venereal disease, and I’d check on new mothers. I’d offer information to each about baby formulas. I remember a single mother who had five children. Seeing how young I was, she questioned my knowledge and asked if I had any children of my own.”

“Back then there were empty lots next our house, and Tim, who was only eight at the time, slid down Arbor to Diamond on a cardboard box and broke his leg.”

The extended Bratt family was locally legendary, legions of them domiciled throughout Glen Park. Her father- and mother-in-law held court, entertaining aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, sons and daughters and grandchildren. “Our family was like its own village, but so was Glen Park, even back then,” said Bratt. “Everything we needed you could find here.”

“Best of all was Connie’s Grocerteria on Chenery Street, where fitGLENfit is now. Constantine Portale owned it, and he ran it with his wife, Rose.”

“Connie was always formally dressed with a tie and apron, and he had slicked-back hair,” she said. “I’d give a key to the kids, say so long and send them to Connie’s or off to Glen Canyon. They’d come back for supper. Connie was handy, and he’d lend Tom tools. Dinner was always family time, where we shared the day’s adventures.”

Some of their Glen Park adventures were extraordinary.

“Once at the Bank of America on Diamond Street, when Holly was 10, a masked man burst in while we were waiting. He yelled, ‘Everyone on the floor.’ He grabbed money from each of the tellers’ drawers and jumped into a waiting getaway car. We never found out whether he was caught.”

“We’d sit at this very kitchen table at dinner and retell stories.”

Stories such as the “pigeon man” of Diamond Street, who fed the birds until they gathered in annoying flocks and the neighbors had to call the police. “The cops weren’t difficult to find, since they all hung out at the Glen Park Station when they were off duty.”

Bratt pointed to her kitchen table, a Formica model of the sort that graced America’s Betty Furness-inspired kitchens in the ’50s. “Connie Portale gave it to us.”

Tom Bratt died in 1994. Karen married and still lives on Hearst Street and has a daughter, Erica, who graduated USC and routinely checks in on her grandmother.

Emily Bratt suffered a massive heart attack in 2012. Holly lives with her and has been a special comfort since Tim died of cancer in 2008.

Years before she retired, Bratt took up watercolor painting, and it’s helped salve the loss of her son. Holly has helped, too, by fashioning a flower, herb and vegetable garden in Bratt’s backyard, an 85th birthday present. Planted with lavender, tomatoes, rosemary, jasmine, sage and dahlias, it’s her sanctuary.

“It’s been my secret Shangri-La,” said Bratt, who uses it to heal and to soothe. It is where she writes children’s stories and poetry, as well as paints.

“It’s my cocoon, and I sit there every day and sip my coffee.”

There she thinks about her husband, Tom, and how he collected her at Connie’s grocery after she finished her St. Luke’s shift and they’d drive up the Diamond Street hill together. She thinks about Holly studying at Higher Grounds in preparation for her nursing degree, and how Laurent Legendre from Le P’tit Laurent told her after her heart attack he’d do anything to help her.

She thinks of Tim, who practiced law and who performed in Bay Area amateur theater productions such as “The Secret Garden.” She thinks about Pusan, and how her navy orders included time in Yokohama en route there to be fitted for a winter coat.

And she thinks about the VA hospital in Atlantic City all those years ago.

“I think about a wounded soldier, a young 21-year-old boy. He’d lost a leg and he was inconsolable.”

“Walter Reed would send rehabilitated vets to our Jersey facility. These men came and attempted to cheer up our patients. One visiting soldier was a bilateral amputee—he had lost both of his legs—and he told my patient he’d be able to dance again.”

“The boy simply turned his face away, saying he never would.”

“Nonsense,” she said the young officer told him. “Let me show you.” He walked to the 23-year-old nurse from Flatbush and swept her into his arms.

“We took a turn around the ward floor,” said Emily Bratt with a smile.