To celebrate the Glen Park Association Website turning ten years old, we are reposting some of our favorite stories from the last ten years.

Two Little League teams faced off on the Thelma Williams Baseball Diamond in Glen Canyon Park on a warm Saturday afternoon in April. The players were six years old, maybe seven. Parents watched from behind a backstop and along the base paths. A father, the pitcher, knelt halfway between home plate and the batter’s box.

He lobbed baseballs to a batter.

The boy took one, then another before he slapped a dribbler to short. The ball bounced once, then twice. The shortstop booted it, then picked it up and rainbowed a toss to first where it hopscotched in front of the first baseman.

No surprise, the runner beat the throw out.

Behind first base, a mother took it all in.

“They’re learning,” she said, “and they’re having fun.”

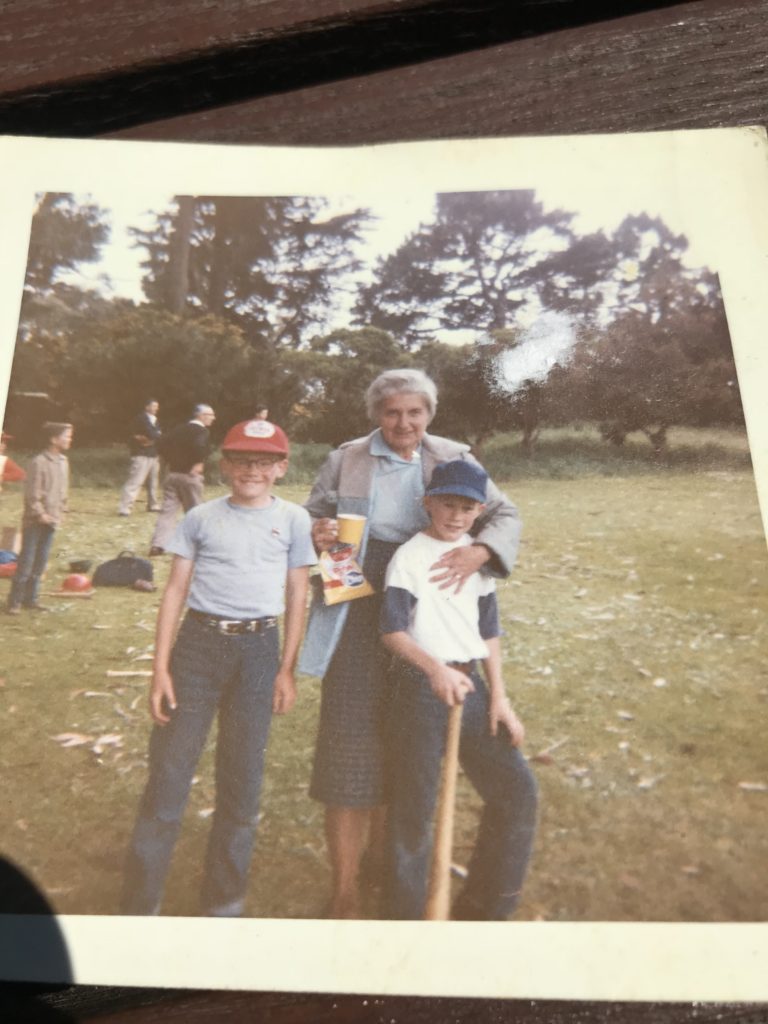

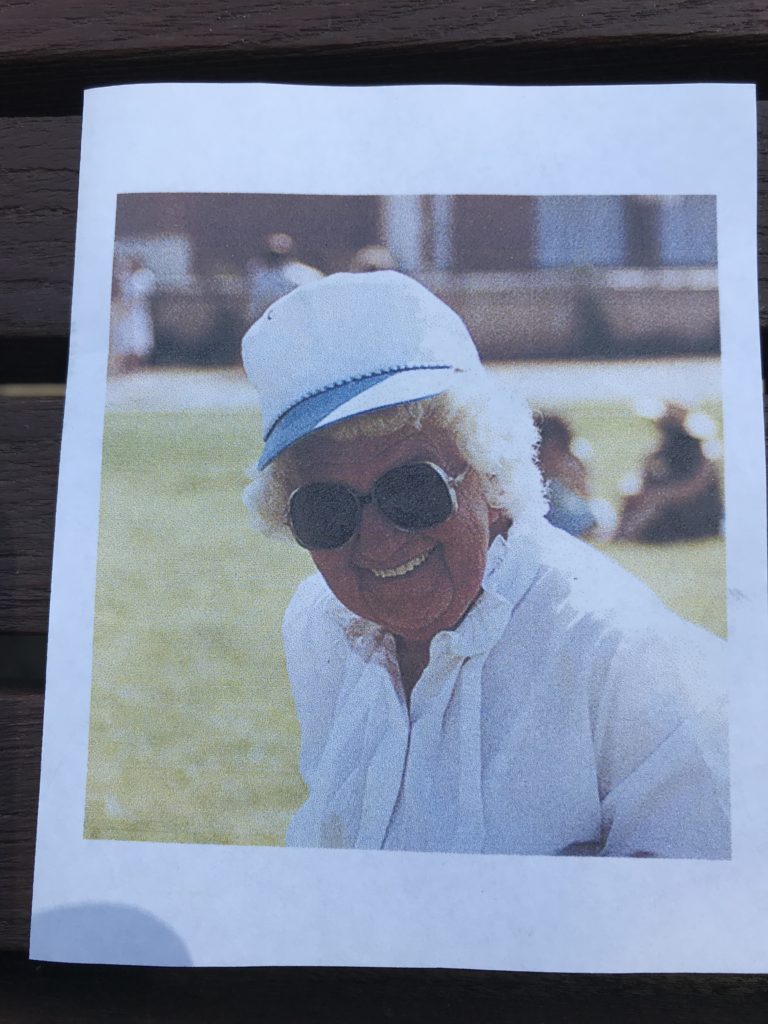

The scene has been played out on tens of thousands of diamonds millions of times. And for more than four decades in Glen Park, it was overseen by Thelma Williams, who coached more than 2,000 kids very much like the ones who competed on April 14.

Williams made her home on Joost Avenue and will be inducted posthumously into the San Francisco Prep Hall of Frame on May 19

She ensured every child she worked with learned baseball and enjoyed doing so.

“I want them to have fun playing the game first,” Williams said early in her coaching tenure. “That way they will learn to love it.”

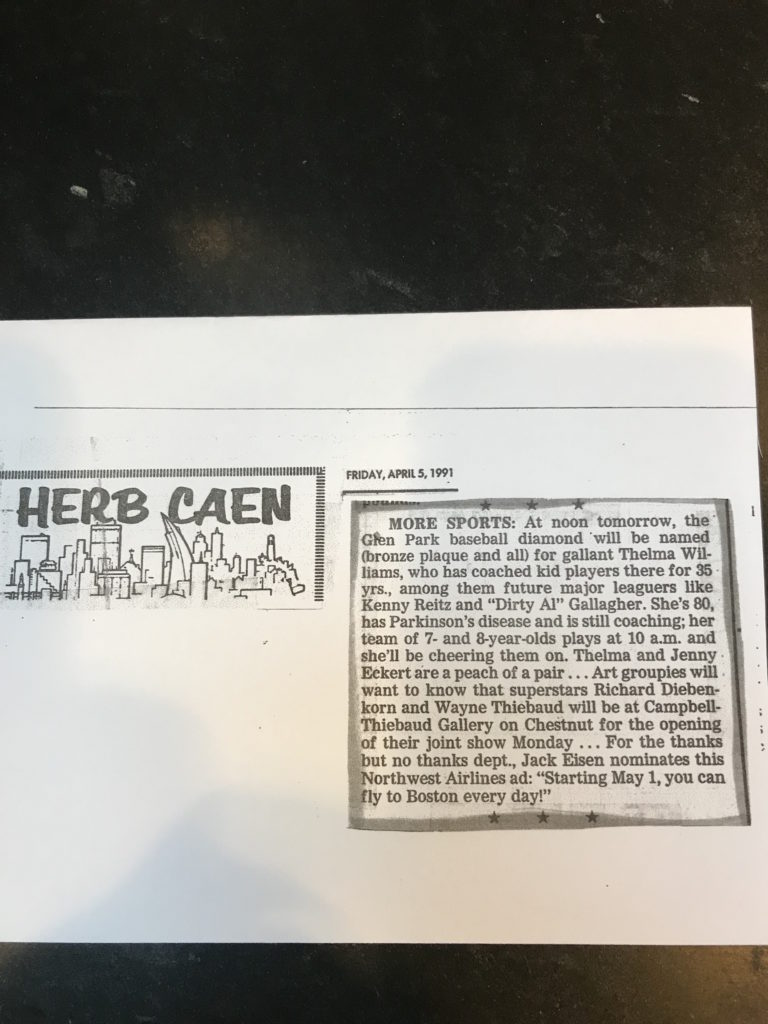

A plaque, put in place in April 1991 honoring Thelma Williams, rests on a cement platform by the baseball diamond in Glen Canyon Park. It’s a testimony to this mid-twentieth century Sunnyside housewife who donated in both time and energy to generations of neighborhood children.

“In the early 1950s, my mother replaced my father as coach in the Rec and Park League. said Mareth Vedder, Williams’ daughter. “I was 10 years old, and I’d accompany her to games.”

Vedder sat on a bench near the Thelma Williams Baseball Diamond left field foul line on April 13, the day before the San Francisco Youth Baseball League game. She fingered memorabilia and photographs of her mother, who passed away in 2000, only a short while shy of her 90th birthday. One of the photos, dated 1952, showed the Glen Park Rec team. Vedder’s older brother, Bob Williams, kneels in front of a dog, his hand resting on the dog’s back. Glen Park is writ large across the front of his uniform.

“My mom was a pioneer, way ahead of her time. It was an era before women became coaches,” Vedder said about her mother, who also worked at Seals Stadium. “An opposing coach early on told her, ‘Go home, wash dishes.’”

Dick Morosi played against that 1952 Glen Park team. Morosi was coached by Grove Mohr, another legendary San Franciscan, a man far ahead of his time regarding gender roles.

Morosi, a retired Westmoor High School (Daly City) teacher and principal, an All City shortstop for then Sacred Heart High School and later a college standout at the same position at St. Mary’s College, is several years younger than Bob Williams.

Brought up in the Portola District, Morosi, who went on to coach varsity baseball at Daly City’s Serramonte High School in the 1970s, has the role of making an introduction for Thelma Williams at the May 19 Prep Hall of Fame dinner scheduled to be held at Patio Español.

“I was nine years old and playing for Portola Playground,” Morosi intends to tell the Alemany Boulevard restaurant audience. “Glen Park always played us tough,”

Not one to ignore a teachable moment, Grove Mohr handed Morosi two pristine baseballs before the Glen Park vs Portola Park first pitch.

“Give these to the other coach,” Mohr instructed Morosi.

“I walked the balls over,” said Morosi, “but I didn’t see anyone who looked like a coach. Then this lady, Mrs. Williams, says ‘Nice to meet you.’ Then she tugs at my cap and she says ‘You just gave the baseballs to the coach!’”

Morosi returned to his side of the diamond. Mohr, who’d served as a Director for Portola, Excelsior and St. Mary’s playgrounds, waited.

“Well, Dick,” he asked Morosi, “Did you learn something?”

Williams pioneer roots go deeper than simply becoming one of San Francisco’s earliest athletic coaches. She was born in 1910, orphaned at 10-years-old and raised by relatives. In 1938 the then-Thelma Kulander married Seymour Williams, a son of Sunnyside family patriarch Sephaniah Williams.

The older Williams operated the Sunnyside Coal & Feed Yard, situated on the first block of Joost, only a Ruthian homerun distance from today’s Glen Park BART station. From the late nineteenth century and into the 1920s many Sunnyside and Glen Park families still burned coal and grazed cattle on byways with names such as Baden, Mangels, Martha and Congo.

As a ten-year old, Vedder remembers those hills, as they led her to and from the Glen Park Recreation Center.

“My mom didn’t drive,” remembered Vedder, the youngest of Williams’ five children. “She and I would carry bat bags to the park, which meant climbing Baden, then along Martha, down Congo and across Bosworth to Elk.”

“One afternoon I was collar boned by a line drive at third base,” she said. “I was so embarrassed. I walked back home, up Congo and Martha to Stillings, then to Nordhoff, down to Mangels and then to Joost.”

“My massage therapist says I still have the scar tissue,” Vedder said, smiling.

Her Idaho-born mom was also pretty stoic.

“I’d get at least three bruises a season,” she once said. “So I’m used to them.”

Williams’ granddaughter, Sharon Swanson, also remembers her grandmother and baseball.

“She’d bundle us up, stick us on Muni and take us all over the city to baseball games.”

The coach had a bit of the poet in her, just as capable of turning a phrase as she was a double play.

By 1966 she was the mother of two sons and three daughters and the grandmother of twelve. When she wasn’t scheduling games, making batting lineups, reserving diamonds, and handing out uniforms for Babe Ruth and Midget leagues, she enjoyed sitting in her 225 Joost Avenue living room and putting her thoughts to paper.

“I have a small rustic cottage with an old-fashioned garden in the back, a small black poodle and a canary,” Williams reflected in those writings. “As I look down upon the garden at the flowers and the apple tree, loaded with green promises of next month’s delicious fruit, I listen to the birds twittering and I think how wonderfully peaceful it is.”

Williams’ idyllic respites never lasted long, though. She could exchange the poetic for the prosaic as quickly an an umpire calls balls and strikes.

After such moments of household repose, she’d segue again to throwing batting practice, hitting fungoes, figuring out transportation to twilight high school games and playing pepper.

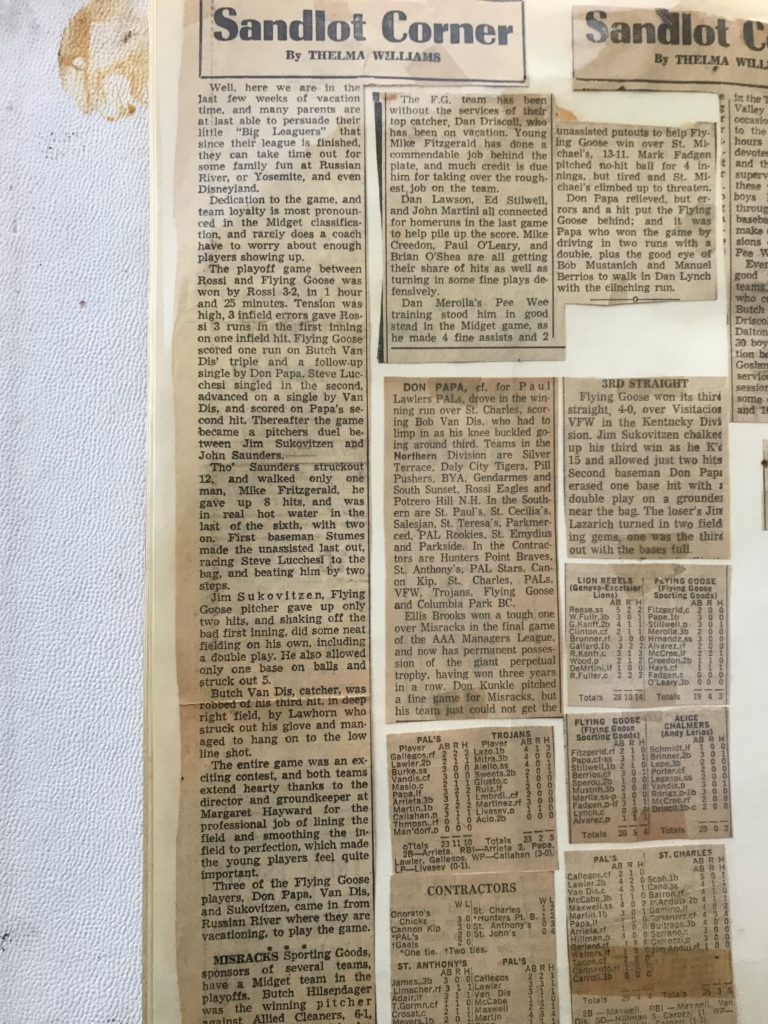

She also penned “Sandlot Corner,” a column devoted to Little League box scores and news, in San Francisco Progress, a local free paper that published from 1918 to 1988.

“I never took batting practice,” Williams confessed at 70. “I just didn’t want my players to know I couldn’t hit.”

“Our Joost house looked over the derelict Sunnyside Conservatory,” Vedder recalled. “In the 50s and 60s we thought it was haunted.”

Unperturbed by Monterey Boulevard specters, Williams would give a key to her Joost home to her children who were used to her not being home, though she did leave snacks for them.

“Even my grandchildren were used to Nana not being home,” Williams wrote on that 1966 morning. “They figure that if I’m not there I’m usually at a ballgame, and they’d think I owned the sporting goods store when they’d see all the sporting equipment there.”

For the most part she depended on the dads and Pete Franceschi, who she lured to PAL baseball, to pick her up with her equipment. Sometimes she called a cab.

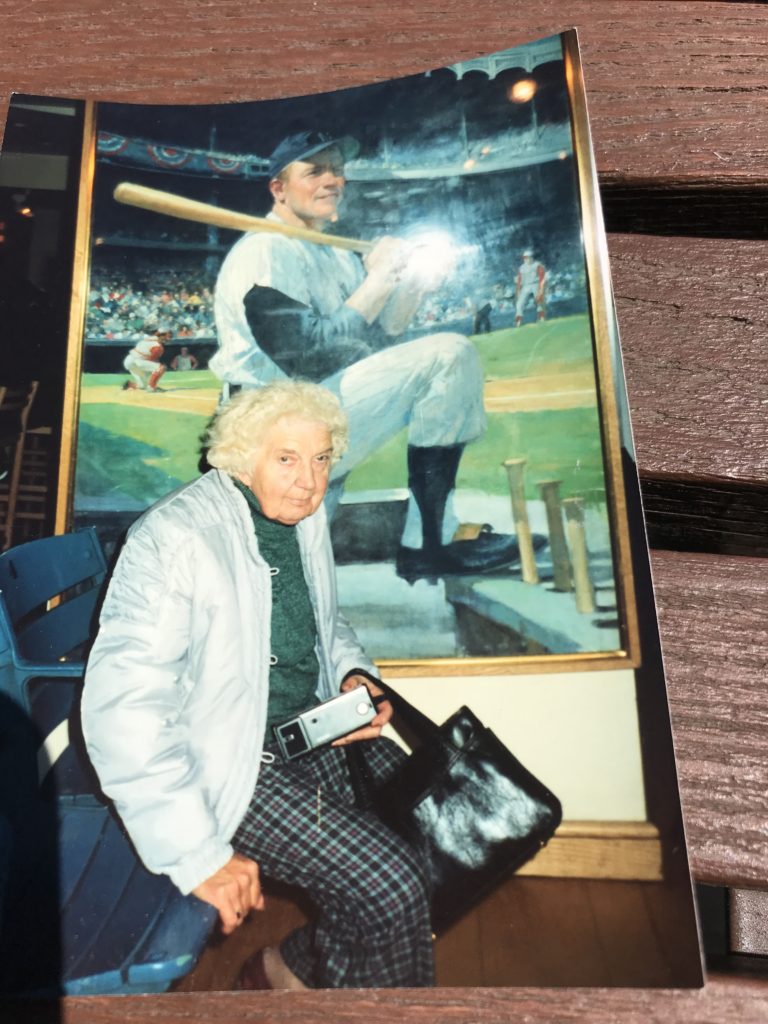

“The cab drivers are generally good sports about lifting a heavy bat bag into their trunk,” she wrote in the mid-60, this woman who shook the hands of Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, and Willie Mays, and who coached the San Francisco-likes of Kenny Reitz, Juan Eichelberger and Al Gallagher. “Most of the cabbies are interested in what I am doing and some refuse a tip, saying ‘Give it to the kids.’”

If it wasn’t a yellow cab, it could very well be a police black and white cruiser that might give Williams a lift.

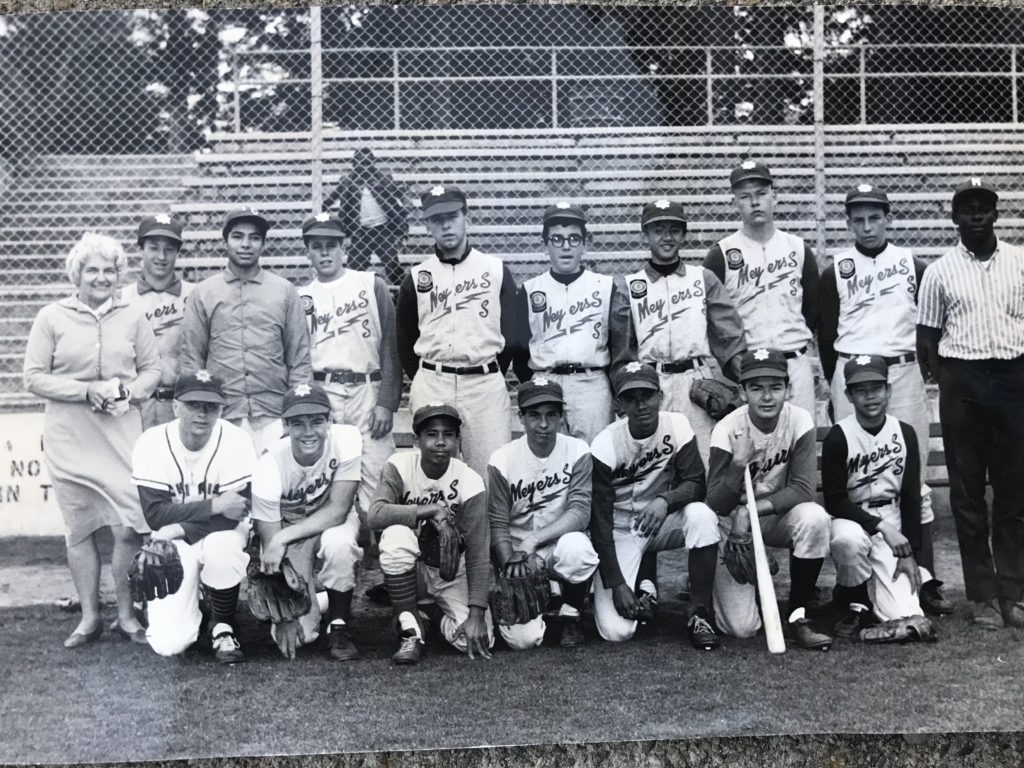

San Francisco police officer, Tom Taylor, played for both Williams’ Meyers Safety Switch and Flying Goose teams in the mid-60s.

Taylor joined the SFPD in 1973 and recently retired. He plans on attending the May 19 Prep Hall of Fame dinner in honor of Williams.

“My partner and I spotted Thelma waiting for the 10 Monterey at 30th and Mission, which would take her to Big Rec,” he reminisced. “She’d come from work at Meyers Safety Switch and had her green duffel bag filled with bats, balls and bases. We were heading back to Ingleside Station, but instead took Thelma to Golden Gate Park.”

“I wouldn’t be surprised to hear that she got rides from a fire chief’s battalion car,” continued Taylor, “Her boys turned into fire fighters, police officers and teachers. We all played for her.”

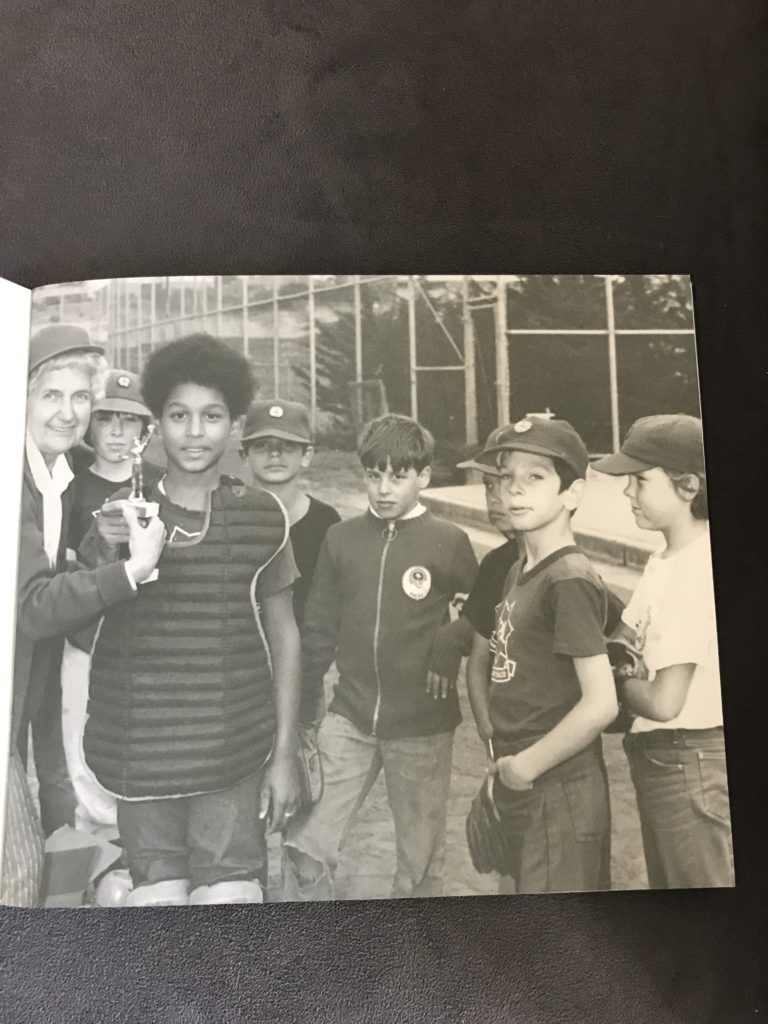

She always called her baseball players “her boys,” Rick Bruce, Police Athletic League president wrote in 2009 in celebration of its 50th anniversary. That year Williams was inducted that year into the PAL Hall of Fame.

One of those boys was Steve Franceschi, Pete Franceschi’s nephew, who played for her Meyers Safety Switch team in 1962. Franceschi is now assistant baseball coach at Sacred Heart Cathedral High School.

“I didn’t have any spikes,” recalled Franceschi, who works with SH pitchers, “so Thelma bought me a pair.”

Paul Lowery, the back stop for the PAL Flying Goose Midgets riffed about cleats, as well.

“Our spikes never seemingly fit and our moms and dads wouldn’t purchase the correct size and they’d tell us ‘They cost money and you’re going to grow out of them quickly.’ So they’d stuff the front part of the spikes with torn remnants of the Chronicleto ensure a snug fit.”

“The great thing about Thelma Williams,” recalled Kevin Martin, the vice president of the PAL “was she would provide kids with mitts and equipment. She made sure kids had enough to eat, that they were involved in school. Thelma always took a personal interest in every aspect of their lives.”

“Thelma was a giver,” echoed former cop Taylor, “If you didn’t have a bat or a ball, she’d find a way to get them out of her own pocket. She broke ground, and she learned along the way and we learned with her.”

Why does Thelma Williams matter more than a half century later?

Onetime Little Leaguer Lowery knows.

“She matters because we had a joyful time when Flying Goose played Max Sobel on the gentle grass in Glen Park in front of enthusiastic parents,” said Lowery. “Mrs. Williams matters 50 years later because she represented a period when it was fun to be a kid and when baseball was King and she was the reigning Queen.”

On April 13, Vedder let her eyes circle the Thelma Williams Baseball Diamond. This year Mother’s Day comes a week before the May 19 Prep Hall of Fame dinner, and the Williams clan plans to meet on the field, as it does every year, to remember Thelma.

“My mom loved robins,” Vedder said, watching a bird alight near the keystone corner. “We believe if it’s possible to return, mom would come back as a songbird.”

By the mid-point in her coaching career, Williams was thinking more about bunts than birds.

“I guess a lot of people think I’m a little bit cracked, and I can’t handle baseball teams,” she wrote, “but after 14 years, the old-timers are now accepting me as their equal and instead of offering me advice they are sending me promising youngsters or any youngster who wants to play ball.”

On April 27, two such youngsters took to the Thelma Williams infield, accompanied by their Noe Valley parents. Adler Jacobs, aged five, selected a bat and stood at home plate; his brother, Devin, three years old, knelt next to his father and mother.

Lauren Menschel stood a few feet from her son. She threw right handed. She underhanded a ball to Adler, who swung from what a baseball scout would liken to a Major League batting stance.

It was a Sunday, it was family, and – like going four for four and hitting for the cycle – it was fun.

For forty years Thelma Williams, donning a red windbreaker, positioned herself near the on-deck circle on baseball fields across the City. She’d pull at her cap, finger her maroon score book. She’d peer at the hitter, a Glen Park or Sunnyside boy. She’d catch her player’s eye as he shouldered his pine from either his right or left side. If there were a runner on base, she’d pantomime a sign. Then she’d echo the dozen words heard by every kid who’s ever laid down a squeeze at home, poked a single through the hole, or slugged a round tripper over a fence.

The same words Bob Williams and Dick Morosi heard and have repeated over a lifetime, words not simply standing in a batter’s box like Adler Jacobs did on a spring day in San Francisco, but that have held them in good stead ever since.

The same dozen words Flying Goose catcher Paul Lowery heard from a Joost Avenue housewife who’d straddle the third base coaches box on a Glen Park baseball diamond.

“Don’t take your eye off the ball; watch it hit the bat!”