Story and photos Murray Schneider

Dia de los Muertos, the pre-Columbian Mexican festival celebrating those who have left us, came to Glen Park for seven days in the form of a dozen ofrendas, offerings created by relatives and friends that remember departed loved ones

From November 1 through Noveber 8, Chenery Street’s Modernpast hosted the displays in Ric Lopez’s shop.

At the closing festivities, Lopez stood by his own presentation, explaining its significance.

Photo 5 – Peter Wolff and Ric Lopez – Modernpast

“This offering is an ongoing gift to our ancestors, but also to those present,” said Lopez, who familial mementoes highlight events from his mother’s life and that of Peter Wolff, his partner’s mother.

Lopez pointed to a grouping of assembled beans and chocolate.

“Our two mothers never met, but one loved beans the other chocolate,” he said. “Always generous, my mother claimed ‘If you have a bean, always cut it in half.’”

Mia Gonzalez, formerly of Encanta Gallery in the Mission District, curated the seven-day event with Lopez. She assembled San Franciscans from different ethnicities to come to Glen Park and exhibit their family possessions.

“Next year we’ll begin earlier,” said Gonzalez, appraising the collections. “We want to use it as an opportunity to teach children.”

“To my knowledge this is the first time such a Latino cultural event has come to Glen Park,” added Lopez.

“The Mexican Dia de Los Muertos gives honor to those who have come before,” said Gonzalez, “and is also inclusive. Artists who shared may have done so earlier in the privacy of their own homes, but never before publically.”

The Day of the Dead is traced to southern Mexico and meso-America, millennia before the Spanish conquistadors arrived from Europe. Originally scheduled in summer, the indigenous peoples festival moved to October 31 through November 2 to coincide with “All Soul’s Day.” In addition to household ofrendas, family members make pilgrimages to loved-ones gravesites, offering gifts, leaving possessions and recalling humorous stories.

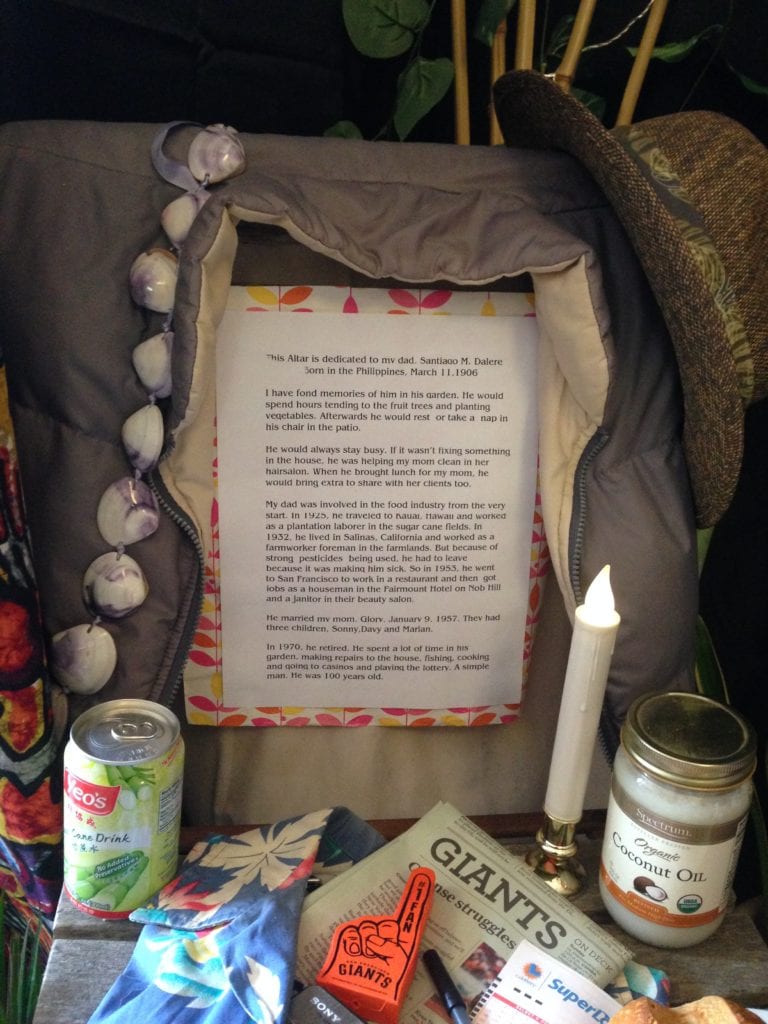

Family heirlooms filled an ofrenda next to Ric Lopez’s alter.

“My father’s name was Santiago Dalere and he came from the Philippines to Hawaii, then to Salinas and eventually to Glen Park in 1957,” said Marian Dalere, who owns Dalere’s Beauty Shop across the street from Modernpast.

“My father’s name was Santiago Dalere and he came from the Philippines to Hawaii, then to Salinas and eventually to Glen Park in 1957,” said Marian Dalere, who owns Dalere’s Beauty Shop across the street from Modernpast.

Dalere’s ofrenda was an assortment of sentimental objects, gathered from years living in Glen Park.

“My father worked as a custodian at the Fairmont Hotel, and he loved sitting in our patio surrounded by his chickens,” said Dalere, pointing to an array of fruits he’d grown in his Chenery Street backyard. “We had apple and pear trees, and he loved to cook using mustard, figs and beans.”

“He’d bring his veggies to my mother’s beauty shop,” she said. “He was so proud of his farming and so glad to get away from Salinas pesticides.”

The toxins had no adverse impact, as Santiago Dalere lived to be 100.

“When he wasn’t gardening, my dad would go to Muni pier and fish,” Dalere continued, gesturing to a nook in her ofrenda festooned with fishing rods.

The ofrenda next to Dalere’s belonged to Janine Rosales who lives in the Excelsior and who graduated from McAteer High School.

“Papa lived on Molimo on Mount Davidson and owned a furniture store at 17th and Mission Streets,” said Rosales, about Nicaraguan Edgard Rosales, who played percussion in the Fairmont Hotel’s Latin bands. “He played conga drums with Cal Tjader, loved dominoes and practiced with clave sticks.”

Rosales’ ofrenda boasted a photo of a healthy canine, whose shortened dog-years matched that of Edgard Rosales, who passed after only 39 years.

“My father named his collie Mambo, after Tjader’s Modern Mambo Quintet,” Rosales explained. “After papa left, Mambo died of a broken heart.”

If Mia Gonzalez needed proof that Dia de los Muertos embraced cultural ecumenicalism, she needn’t have looked further than Gary Fusco, who stood next to an offering to his mother, Paulina Murcurio Fusco.

“My mother was a Sicilian and loved her kitchen,” said Fusco, whose 25-year old daughter Gabrielle helped fashion their ofrenda, a trove of baking pans, cheese graters, rolling pin, wine bottles, cloth napkins and a cookbook. “Creating this alter is like bringing my mother back and remembering her.”

Latina Anita de Lucio moved closer to Fusco’s ofrenda, glancing at her own alter.

“My father always made the point that we must present ourselves professionally,” she said. “This week has been a forum for expression, a gathering that brings us from grief to creation.”

In her turn, Janine Rosales couldn’t have agreed more, making her initial foray into public expression.

“For someone who wasn’t sure,” she said, smiling, “I think I did a good job.”