Story and photos by Murray Schneider

Before I retired I taught eleventh graders American history, and each morning I’d drive to school by descending O’Shaughnessy Boulevard.

Going down the hill, O’Shaughnessy Hollow was on my right and Glen Canyon was on my left.

Glen Canyon, the larger of the two, is 70-acres of natural area, one of 31 in San Francisco the Recreation and Park Department manages with the assistance of a corps of neighborhood volunteers.

I’ve been a member of the corps for seven years now.

“If you ever return to the district,” my former school superintendent jokes, “you can come back as a gardener.”

Which is saying a lot for someone who has lived within minutes of Glen Canyon for 41 years, but couldn’t identify a daffodil from a dandelion before he began pulling weeds along Islias Creek, and who has avoided removing weeds from his own backyard that overlooks Glen Park Elementary School.

Glen Canyon work parties, which I enjoy, are scheduled each Wednesday and Saturday. They are organized by Friends of Glen Canyon Park and supervised by the Rec and Park’s Natural Areas Program gardeners.

Neither gardeners nor volunteers enter Glen Canyon, which boasts excellent forage and nesting habitat for a variety of migratory and resident birds and one of two flowing creeks remaining in San Francisco, without a detailed management plan.

Neither gardeners nor volunteers enter Glen Canyon, which boasts excellent forage and nesting habitat for a variety of migratory and resident birds and one of two flowing creeks remaining in San Francisco, without a detailed management plan.

The Significant Natural Resource Areas Management Plan (SNRAMP), written in 2006 and currently undergoing a routine Environmental Impact Report (EIR), offers such a plan, spelling out a 20-year path that guides management actions and ensures stewardship of the community resource.

Not unlike the daily lesson plans teachers follow, which morph into semester and then yearly plans.

The management plan is intended to guide natural resource protection, habitat restoration, trail and improvements and maintenance activities, and the section devoted to Glen Canyon and O’Shaughnessy Hollow identifies a number of goals with respect to conservation, education, stewardship and recreation.

In the 1930s, City engineers dynamited obstructing Franciscan chert and constructed a swath of road, O’Shaughnessy Boulevard, which winds between Portola Drive to Diamond Street.

It divides Miraloma Park from Glen Park.

On its Miraloma side, O’Shaughnessy Hollow remains off limits to the public.

Not so with Glen Canyon, adjacent to both Glen Park and Diamond Heights.

Here are found some of the largest, most impressive and accessible rock outcrops in the City, habitat to red-tail hawks and great-horned owls. Here are found extensive grassland habitats for butterflies and other insects. Glen Canyon boasts 23,000 feet of trails, many of which are recreational, and here Islias Creek is covered by a canopy of dense arroyo willow, refuge to numerous bird species.

It’s in Glen Canyon I’d walk my dog as she strained against her leash to get at songbirds, and it’s there I’d bring my two daughters, now grown and with careers of their own.

The management plan is both specific and prescriptive. As a retiree, I’ve devote hours to removing invasive plants, engaging in erosion and sediment control, enhancing stream restoration, making trail improvements, collecting seeds and planting California drought tolerant plants in my neighborhood’s portion of the 868 acres of natural areas remaining in San Francisco.

It was seed collection that occupied me for several days this summer, and it was Jenny Sotelo, a Rec and Park Department gardener who demonstrated how.

In August, along the west side of Islais Creek, she and I scouted for blue elderberry seeds. We didn’t have to look very long because an elderberry tree stood above the dry creek between the Recreation Center and Silver Tree Day Camp. Wielding a poll pruner, Sotelo identified a leaf sprinkled with seeds. She nipped a branch and a leaf floated to the ground. Collecting it, she placed it in an envelope.

The blue elderberry is typical of Glen Canyon’s diversity. Along with eucalyptus, prized for being one of the few nesting locations of red-tailed hawks and roosting owls, elderberry flowers offer sustenance and sanctuary to humming birds. Other passerines devour its fruit, as well.

As always, after seeds are gathered, Sotelo trucked them back to a Golden Gate Park nursery where they are propagated for later reintroduction into the canyon.

The management plan details nineteen sensitive plants in Glen Canyon and O’Shaughnessy Hollow. Red columbine abounds, never more so than now because of Natural Areas Program restoration efforts in Islais Creek’s designated areas. Not far away, silk tassel bush is camouflaged among California blackberry scrub, and spring red berry peeks from west side chert outcrops.

Arguably, yellow-eyed grass, above the boardwalk in the canyon seep, is most coveted, as it is the only known population in San Francisco. Johnny-Jump-ups may come in a close second, though, ensconced along the eastern slope grassland. The flower is host to the Silverspot butterfly, which is listed on the Federal Endangered Species Act.

Glen Canyon’s diversity is an outdoor classroom for visiting school children, and they often troop by us while we work, as a group of three-and-a-half years old did this September.

Above them this September, Sotelo led me along the eastern slope. Berkeley Way and Crags Court loomed above us, silhouetted behind craggy rocks

Our goal: to reconnoiter for aster and coyote bush, determine if the wildflower and shrub were in seed, collect, sow and eventually return each to their canyon habitat. Aster is native to California and the genetics of this perennial flower are suited to what Rec and Park labels its Zone 2/moist zone seed collecting climate area.

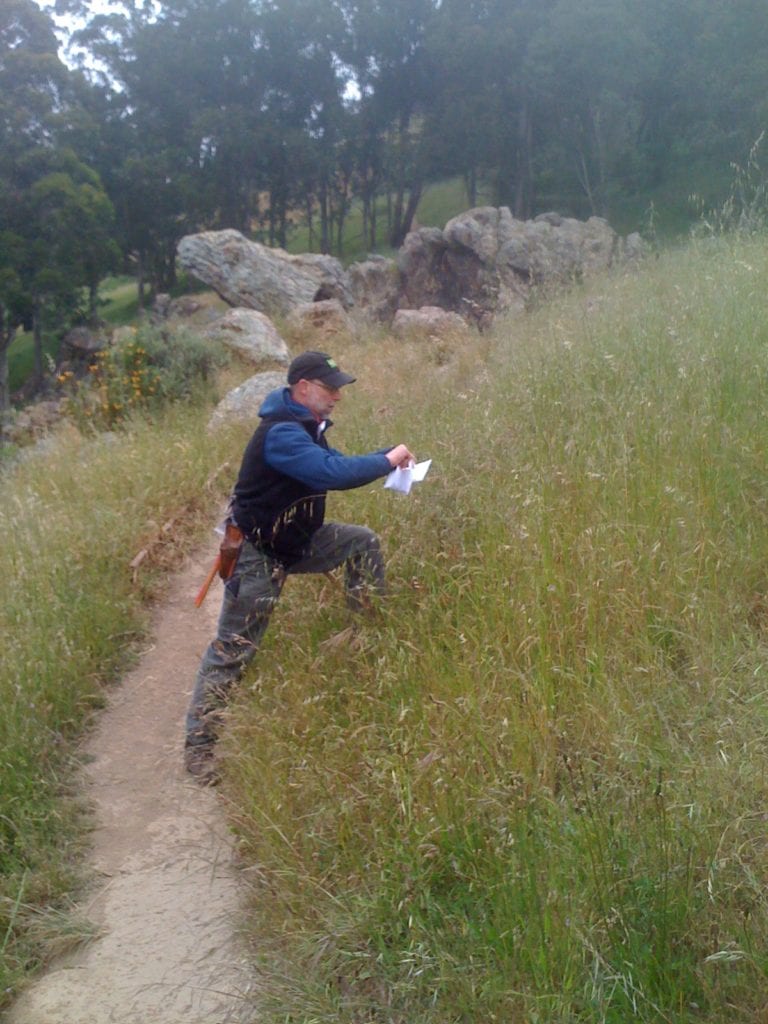

We ascended from Alms Road, navigating a steep incline made difficult to climb because of loose pebbles. Jenny Sotelo is my youngest daughter’s age, and she’s more sure-footed than I am. We bypassed clumps of coyote brush, eyeing the hillside for the aster that bumblebees and butterflies find nourishing. The coyote bush was in seed and I placed some in envelopes. Except for a California oak or two, trees are rare on this hillside. Trees, however, occupy nearly thirty per cent of the canyon, approximately 17 acres. Pine, eucalyptus, redwood, cypress, coast oak and ubiquitous riparian willow abound, each sharing space with canyon scrub and grassland.

A nearby dog walker relaxed with her children on the slope while her dog bounded down the hill. It raced near purple-needle grass, coming close enough to trample it. Off leash dogs contribute to erosion and are a reason reseeding becomes significant. Not without its critics, the management plan recommends closure or reduction of some dog play areas, as well as judicious tree removal.

Sotelo requested the dog owner leash her pet in this sensitive area and the woman complied.

We reached Berkeley Way. A house that had caught fire, which resulted in the tragic death of two firefighters in June 2011, is now rebuilt and indistinguishable from adjacent homes. We hadn’t located any alder in seed, but Sotelo volunteered it might be found at Bay View Hill, which receives less fog and is in the dry eastern climate zone.

Instead of retracing our steps, we walked along the rim of the canyon before descending a less precipitous path. We came upon a house on the triangle at Berkeley Way that had stationed a bird feeder in its backyard.

Birds hopped along its edge, eventually leaving, possibly making their way back to the creek-side blue elderberry tree where we had begun our earlier summer seed collection efforts. Below the feeder, ornamental impatiens flowered purple and white along the fence.

A bird feeder in such close proximity to a natural area makes for a teachable moment, one mixing and matching home dwelling next to public open space. It’s the sort of metaphoric comparison I’d have wanted my students to think critically about, one that signals connectivity between urban settlement and rustic nature.

Envisioning San Francisco’s natural areas as belonging to no single interest group, Rec and Park does exactly that. It imagines space such as Glen Canyon as home to coyotes as well as dogs, habitat for trees as well as grasslands, recreation for day hikers, open-air laboratories for school children, playgrounds for summer campers, and domain to insects and all manner of critters.

It’s no coincidence, then, that on March 11, 2014 Natural Areas Program manager Lisa Wayne, the architect and visionary of the NAP, was awarded a SPUR Good Government Award. Largely responsible for developing its programmatic framework, Wayne hired 11 NAP staff members, preserved and cultivated some 10,000 native plants and created a large group of citywide volunteers who have contributed $4.7 million in volunteer hours.

“It now awaits the San Francisco Planning Commission’s certification that the environmental impact report done for the management plan is complete, accurate and up-to-date. The plan’s adoption is given by the Rec and Park Commission, which then makes it policy and brings to fruition years of work performed by City employees and volunteers.”

I spent the last five years of my career as a school principal. Several of my colleagues wink that coming out of retirement as a groundskeeper might be considered a promotion. Educators who’ve made the switch from the classroom to administration are often asked which they found most fulfilling.

For me, the question’s a no brainer.

Just a classroom, the kids, and a daily lesson plan.

Not long before my summer seed expeditions, a UPS driver, Mike Lefiti, relaxed, taking a lunch break, near the angelica rocks on Berkeley Way. He parked his truck not all that far from where we had looked for alder and coyote bush seeds.

Mike was my student several decades ago.

I walked up to him. Mike’s a big man now and he was a big teenager back then, and he’s a recognizable figure in the neighborhood.

“I come here often,” he said. “I love the view.”

Jenny Sotelo walked over, and I could read her expression.

“He’s a former student,” I said.

I run into my students a lot. We retired teachers always do.

It’s always best encountering them near Glen Canyon.