Story and photos by Murray Schneider

I didn’t know Jimmy Ryan all that well. I’d see him on the Fridays I dropped by Bird & Beckett, to catch his ensemble serving up bebop at the bookstore. On the second Friday of each month, Jimmy sat at the rear of Eric Whittington’s stage, leaning over his drums, usually wearing a T-shirt, a shock of white hair curving across his forehead.

On those evenings, the only time Jimmy looked happier than when his sticks supported the band’s beat was when his wife Rory walked in, usually near the end of the first set, and took a seat in the audience.

Jimmy left us suddenly this July, a victim of a heart attack and a big part of the Bird & Beckett community took a hit.

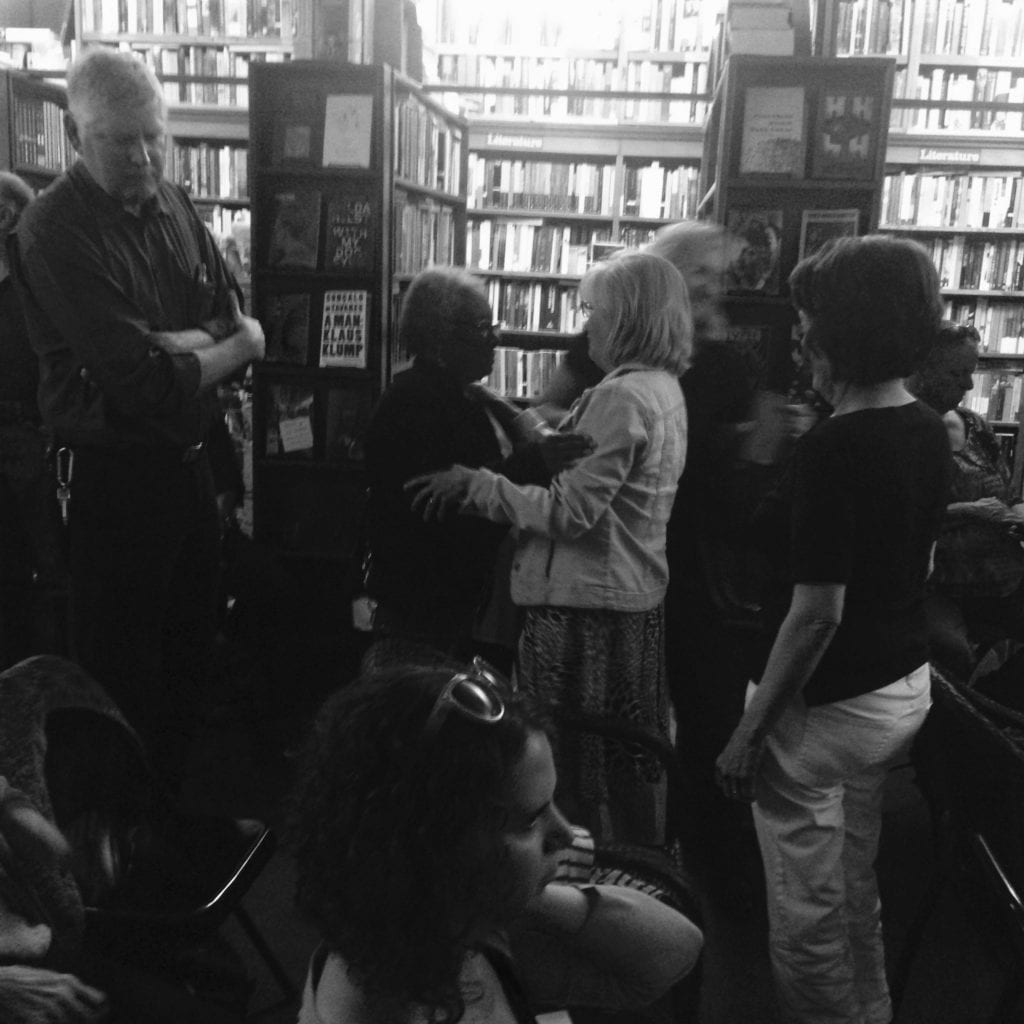

Bird & Beckett bookseller, Eric Whittington, wasn’t about to let Jimmy’s passing go unnoticed. On August 14, nearly 100 jazz fans crowded into his bookshop, listening as Jimmy’s Bird & Beckett BeBop Band paid tribute to its fallen leader. When they finished, they’d performed nearly three hours of jazz improvisations.

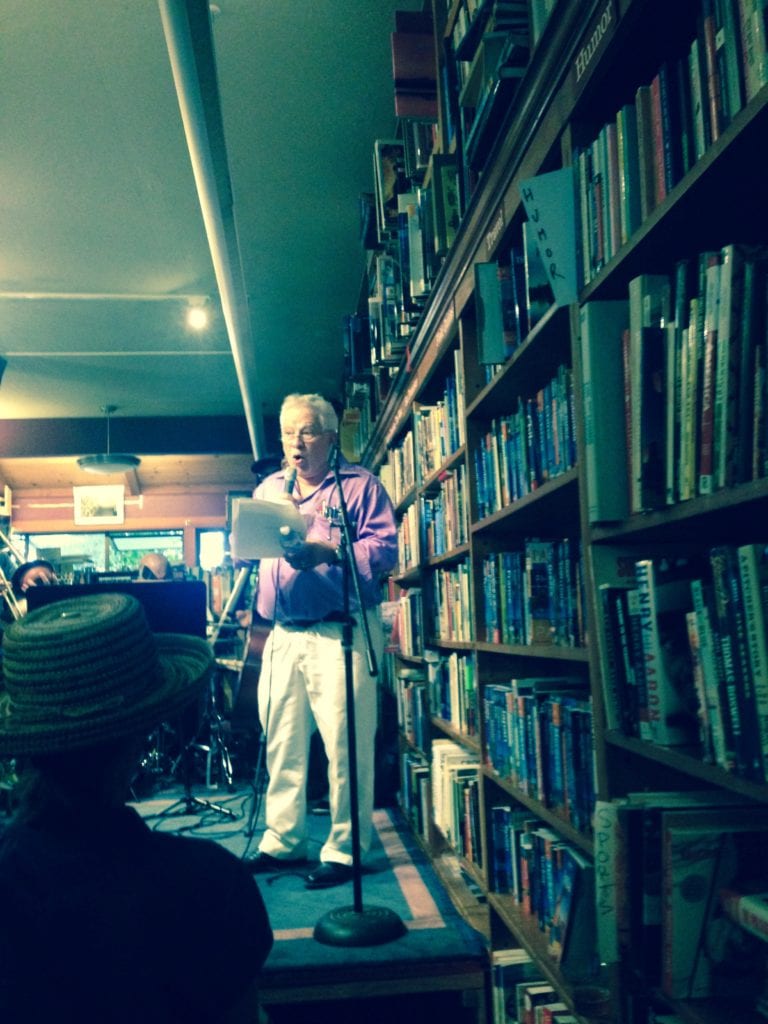

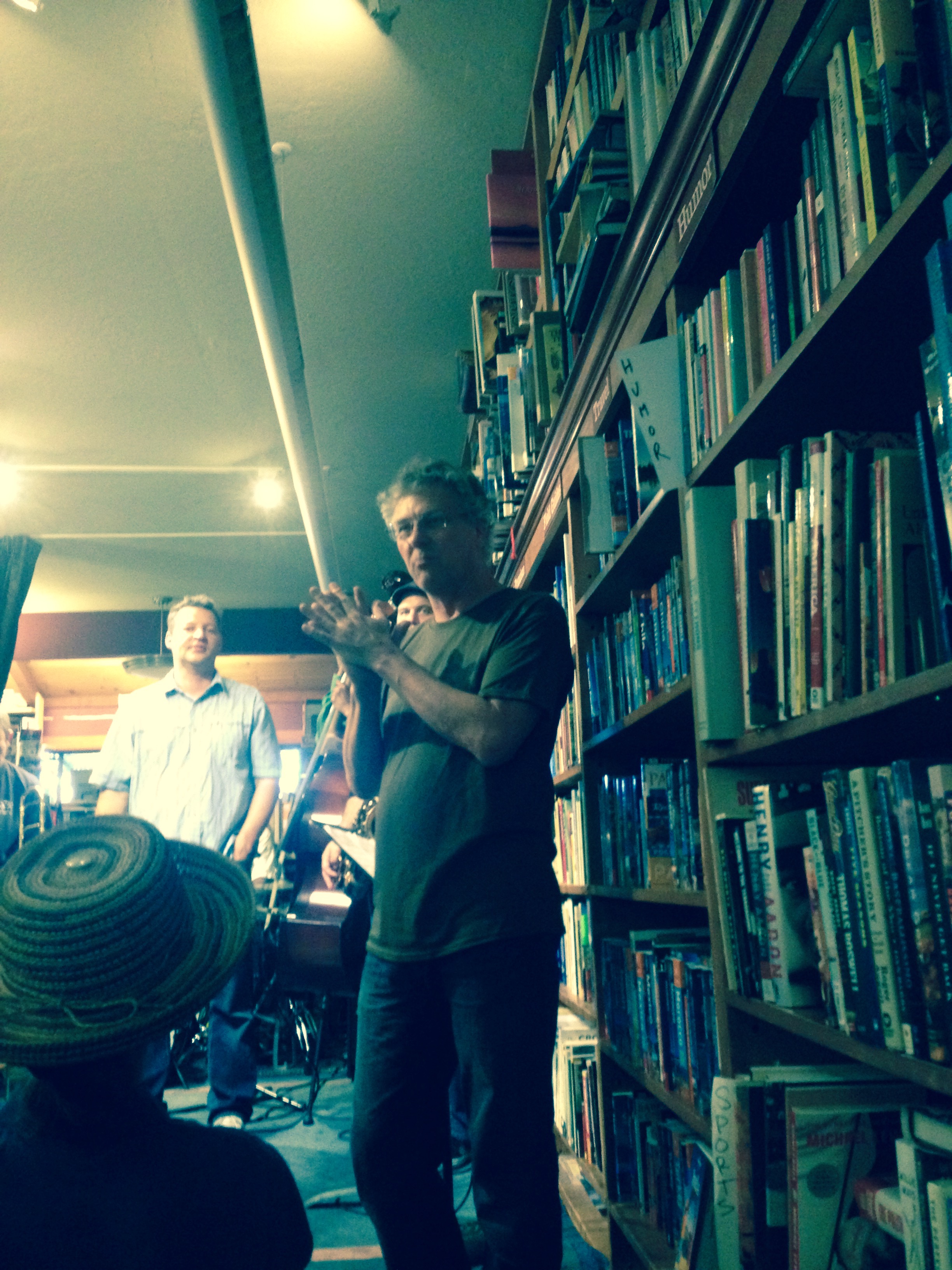

Whittington took the stage at 5:30 P.M. and stated a few simple facts. How Jimmy first began playing the bookstore venue in 2002 when jazz chanteuse Dorothy Lefkovits brought in a trio led by guitarist Henry Irvin. While at the gig, Jimmy noted a flyer advertising tenor player Chuck Peterson’s trio. Jimmy had known Chuck. They hooked up again, and the long-running “jazz in the bookshop” series was inaugurated.

“This is Jimmy’s band,” said Whittington, pointing behind him to Stu Pilorz, Joe Cohen, Don Alberts, Ron Marabuto and Bishu Chatterjee. “This is Jimmy’s night.”

“Jimmy, on drums, drove and supported the band — and his experience in the music and the business ground them,” Whittington e-mailed me several days later. “He was trusted and respected and appreciated for his experience, his love of the music and for the respect he showed the other musicians of whatever generation.”

2015 marked sixteen years of jazz in the bookstore. Jimmy and Eric, inextricably bound by chords of jazz riffs, had celebrated together on May 22 when Jimmy fronted a quartet of players who’d all played with one another in the shop at one time or another.

That was the last time I’d seen Jimmy. After he’d threaded his way between milling members of the audience during a set break, he served up his patented smile.

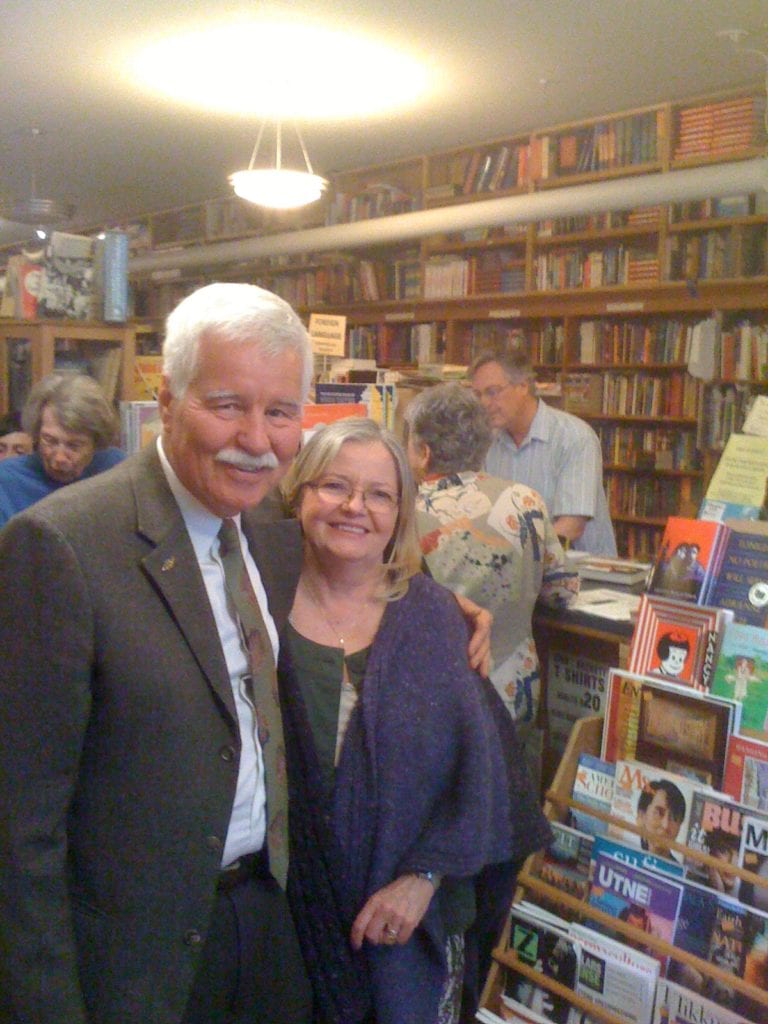

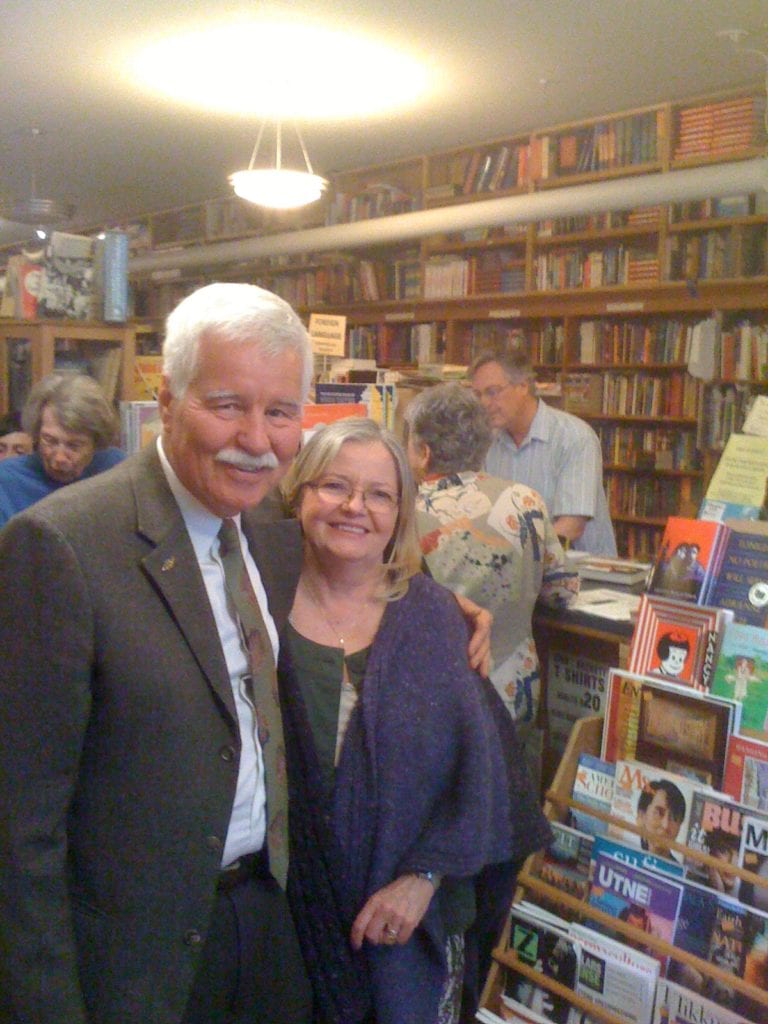

We shook hands. I’d written several pieces about him over the years, one about how he’d met Rory Donovan, a Sutter Health Care nurse, twelve years earlier when she’d dropped by the bookstore in April 2003. Eric’s bookshop was still on Diamond Street then, and Jimmy knew the moment he’d put his eyes on her she’d become his life’s partner.

They’d been inseparable ever since.

Jimmy shared how he and Rory had recently returned from a Hawaii vacation, and how he’d a dicey minute or two while snorkeling. Finding himself pinned against several rocks, he’d only managed to extricate himself with some difficulty.

Then, only months later, while walking with Rory on the Fourth of July weekend he’d collapsed. Rory administered first aid while she waited for paramedics to arrive.

“Jimmy was very patriotic,” Rory told me later, “so this was always a special holiday for him. We’d gone to a Monterey Independence Day parade with friends, then to church and had lunch. Then Jimmy played his drums and then we went on our hike.”

Jimmy Ryan was born in Los Angeles in 1939 and raised there with his two sisters, Midge and Bonnie. At 13, a cousin introduced him to jazz, and he began playing drums at 18. Jimmy moved to San Francisco in the 1960s. With his first wife, Pat, he raised a family of six children. One of them, Joel, is an accomplished jazz trumpeter in his own right.

About the time Jimmy perfected his chops at clubs such as the Fillmore’s Jimbo’s Bop City and Ronnie’s Soulville and the Jazz Workshop in North Beach, I had began a teaching career, experiencing all the predictable doubts facing first-year instructors. To steel myself for each Monday morning, I’d tune into DJ Bobby Dale on Sunday evenings. Bobby programmed jazz luminaries such as Ruby Braff, Bucky Pizzarelli, Stephane Grappelli, Django Reinhardt, and Blossom Dearie, introducing each in an improv stream of consciousness worthy of James Joyce.

A half a decade before, while in college, I’d wander along Broadway. Turk Murphy’s and the El Matador were my destinations. Fantasy Records LPs, featuring, Dave Brubeck, Cal Tjader and Chet Baker continued to be a big part of my life for years afterward as I wrote my lesson plans.

Then, in 2006, just a fifteen-minute downhill walk from my house to Bird & Beckett I found Jimmy playing. It was like closing a circle.

With Rory sitting in the third row on August 14, after 30 minutes of music, after writer Jeff Kaliss recited “Jimmy Ryan, Jimmy Ryan,” a poem penned by piano player Don Alberts, bassist Bishu Chatterjee approached the mic.

“We’re very happy and very sad,” said Chatterjee, who’d been with Jimmy since the bookstore beginning. “Jimmy touched us all, connecting us to one another. I’ll miss my dear friend, his zest for life, his love of family and his passion for bebop drumming.”

Chatterjee cradled his bass, hugging it close. In a moment, he kicked off an original composition.

“I wrote this for Jimmy and call it “Indra’s Jewel Net” because I was impacted by Jimmy’s connection for life, both on the bandstand and off,” Chatterjee told the audience. “As the Hindu myth goes, if you touched one of Lord Indra’s jewels, it would reflect on others in the net. Jimmy touched so many people.”

Later, Joel Ryan stepped to the stage, phrasing soulful notes in his father’s memory. Afterward, sandwiched between stacks of used fiction titles, he reminisced.

“This was one of my dad’s favorite places,” he said. “My dad met Rory here, and he liked sharing it with as many people as he could, especially buying Bird & Beckett gift certificates for his grandkids.”

Don Alberts walked by, his fingers fresh from a stint on the piano.

“This bookstore,” he said, winking, “is just Eric’s left handed way of getting a jazz club.”

“Jimmy loved the scene here and was convinced that Bird & Beckett would go down in history as a key episode in the history of jazz in San Francisco,” agreed Whittington. “He knew that it was ongoing, barely started and yet already significant and with a great future.”

Before the second set, guitarist Scott Foster sat by himself on the stage, tuning his instrument. Near him rested a photograph of Jimmy.

“You could see it in his face. You could see the joy,” said Foster, who teaches music at Urban High School and who broke in with Jimmy. “Jimmy always said ‘yes, yes,’ and he made a place for me and was always kind to me.”

Eric Whittington left no doubt as to Jimmy’s role as a Founding Father.

“As an elder, Jimmy nurtured players,” he said. “The way he assembled his band pointed to his desire to bring good musicians into the fold and help them express and extend themselves. He and Chuck Peterson, Don Prell and Scott Foster have all made it clear that they know this is a home to the music and to the musicians, and to the people who love to hear them play.”

Jimmy nurtured more than band mates. With Rory, he left nine children and seven grandchildren.

Together since 2003, she is philosophical about her loss. “Of course, there were more years ahead of us but it was not to be,” she said. “I’m grateful I could spend these final years with him.”

I spent decades teaching high school juniors about Abraham Lincoln and only recently ran across what he’d said sometime between splitting rails in Indiana and speechifying at his Second Inaugural.

“In the end, its not the years in your life that count,” Lincoln opined, “it’s the life in your years.”

“I’ve heard what Lincoln said, but it takes on new meaning for me now,” Rory wrote me. “Jimmy was a man who packed a lot of life and love in his years from his work in prison ministry and at our church, to playing music, to spending time with family and friends, and to educating himself about issues that mattered to him.”

Before he stepped from the stage, after voicing Don Alberts’ ode to Jimmy, Jeff Kaliss summed matters up pretty well, possibly thinking of the Bird & Beckett musicians who’d gone before Jimmy — guitarist Henry Irvin, alto saxophonist Bishop Norman Williams, bass player Ron Crotty and pianist B. J. Papa.

“We need to treasure these people while we have them,” he said.

For her part, Rory Ryan treasured one above all.

“A life well lived, Jimmy Ryan,” the jazz drummer’s wife e-mailed me. “To the very end he did the things he loved, served the God he loved, and lived a life of joy and gratitude.”