By Murray Schneider

Several middle-aged athletes gathered one recent afternoon around the free-throw line at Glen Park Recreation Center’s basketball court, tuning up for the first of dozens of afternoon and evening half-court pick-ups games.

“They’re our senior statesmen,” said Oskar Rosas, 46, recreation coordinator at the Depression-era Rec Center, which would remain open until 9 p.m. to accommodate the squads of players.

Rosas, who has worked for Rec and Parks for 20 years and who graduated from George Washington High School, studied the quartet of hoopsters taking jump shots and driving to the net at one of the last “pit” gyms remaining in San Francisco.

Pit gyms, dating from the early twentieth century, are no longer common on the City recreational landscape. They’re called pit gyms because their permanent bleachers aren’t retractable, as you’d find at high school or college gymnasiums today. Instead, they feature two permanent sets of bleachers. (Glen Park’s gym has only one set of bleachers.) From their perches in the stands, viewers look down upon a “pit” to watch 3-point shots or rare underhand free throws.

Vince Terry, 54, was sinking left-handed set shots from 15 feet out. Limbered up, he launched a jump shot, which swished through the net. “I return here out of loyalty,” said Terry, a 1974 graduate of Balboa High School.

The ball bounced to the floor, where Jerry Williams, 48, picked it up, tapped it a couple of times on the floor and then pumped it back to Terry.

St. Mary’s Park, Sunset and Potrero Hill playgrounds all have similar courts, all built 15 or 20 years after Glen Park’s, all constructed in a Quonset hut motif reminiscent of World War II military barracks.

To experience an authentic double bleacher pit gym these days, you’d need to go to Daly City, where Vince Terry now lives. Jefferson High School still boasts one, built with the same Depression-era WPA (Works Progress Administration) funds that constructed Glen Park’s facility.

Across the floor, against an opposite wall, other players laced up sneakers, stretched, dribbled and tossed in layups.

“I’ve been coming here since I was 17,” said Terry, who has a job with Avis Rental Car. “It’s right in the middle of the city and I get back here sometimes three times a week.”

Williams, who has been returning to Glen Park for 30 years, scooped up an errant ball and angled a hook shot toward the rim. “I like the atmosphere here,” he said. “It’s like home, lots of good vibes.”

Other players began trickling in, stopping to scribble their names on a chalkboard that scheduled 24-point matches. They walked to a court at the far end of the floor and began serving up shots. Twenty years younger than the 40- and 50-somethings, they attempted stuffing dunks, but the balls ricocheted from the bucket.

Terry looked over his shoulder, appraising the competition. “They’re more athletic,” he conceded, “but us old guys will win because we understand the game.” He dribbled from the key and banked a shot that swirled around the rim and then eventually fell through the net: “24-18, we win,” he predicted.

Across the hall, Rosas sat with Clay Breitweiser, another recreation coordinator, and Bart Borg, 59, who retired from that same job in 2010. Borg is from the old school. In 1975, when he first put a playground whistle to his lips, he was called director, and he was responsible for organizing afternoon and weekend sports teams when competition among neighborhood playgrounds was common. These days his former job, which Rosas now has, involves renting facility space and charging for yoga classes as well as modeling the art of a one handed-jump shot.

“I liked watching kids grow up into young men and women,” said Borg, who worked at Glen Park playground for 15 years. “I liked seeing them become citizens.”

Borg supervised a playground Neverland, where kids chose up sides, where good sportsmanship was as important as winning, where skill was valued – but never at the expense of hurt feelings or physical injuries, where athletic eligibility required only a sweatshirt embedded with grass stains, a pair of jeans with ironed-on knee patches and a fielder’s mitt burnished with coats of Glovolium.

And if you didn’t have a glove, Borg would rummage through his equipment closet to find you one. “A place like Glen Park was a melting pot,” said Borg, “a place a kid could try out his skills.”

Playgrounds, all those years ago, were where kids simply could be kids, where your ZIP code meant little, but where you hit in the batting order did, where respect was earned by how far you spiraled a football down the field, and where you worshipped was unimportant, but your ability to win a game of Around-the-World was.

To save money, the City now schedules “specialists” to do what Borg once did: organize basketball leagues, schedule tennis lessons, umpire softball games, supervise soccer matches and hand out ping pong paddles, checkerboards and chessmen. Now specialists move like nomads from one playground site to another.

Mike Gualco, 53, a neighborhood fixture, wandered in and leaned against Rosas’ wall. “I remember the trampoline classes,” said Gualco, who has lived on Paradise Avenue his entire life.

In those days, San Francisco was flush with funds and was never shy dedicating dollars to its children. “In the summer the directors took us on fieldtrips,” Gualco reminisced. “Once we even went to Santa Cruz to ride the roller coaster.”

Rosas stood and gestured outside. Parents pushed children on swings and nannies watched their charges gain steam down a slide. “We capture them at this age,” said Rosas, whose kinesthetic thrill these days is limited to exercising his vocal chords along with the musical Tiny Tots he supervises. “But when they get to be 5 or 6, they don’t come back and we lose them.”

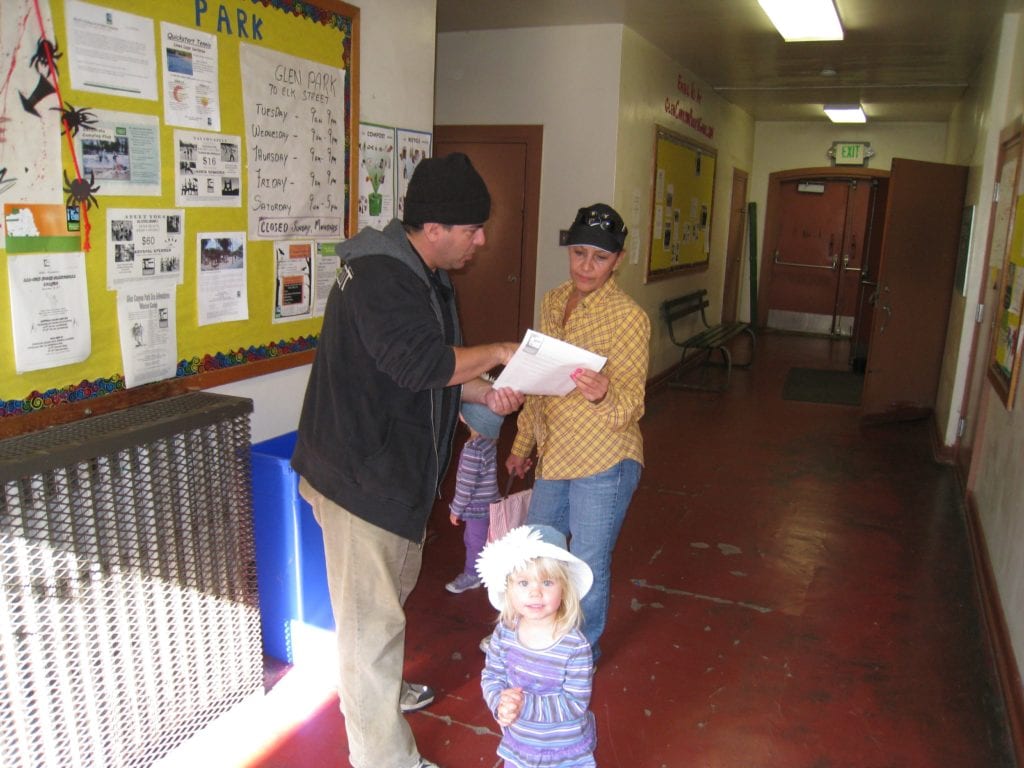

To reverse that trend, Rosas schedules what he calls Community Council meetings to obtain input from parents about which activities can attract their 7-, 8- and 9-year olds, particularly in anticipation of the $5.8 million Glen Canyon Park Bond Project funds that will upgrade the Rec Center, introducing state-of-the-art and age-appropriate playground apparatus.

“After kindergarten there’s a disconnect,” Rosas said. “We’re trying to determine what we can do to build community.”

Clay Breitweiser, who oversees Rec and Parks’ nature class program, and shares an office with Rosas, leaned back in his chair. “Glen Canyon’s natural area is a magnet,” he said, while planning a two-week winter day camp. “We hope by showing 7- through 10-year-olds our trails and habitat and doing team building, we’ll get them to return.”

In the gym, the three-on-three game heated up. Rubber soled shoes screeched on the hardwood and echoed across the hall. Vince Terry skirted past an opponent, passed off to Jerry Williams, who drilled the ball back to a third player who took a jumper and scored.

Rosas runs open court several afternoons and evenings a week, a tradition that goes back decades, way before Borg’s tenure. But Glen Park playground, so close to BART, attracts players from all over the City, even the Bay Area, making it a favorite of basketball lovers.

Terry’s prediction got the score wrong. The Old Guys put away the Young Turks 24-to-16. “They’re good,” said Oskar Rosas. “There’s never any commotion, and rough play isn’t tolerated.”

Devall Porter, 49, who lives in the Bayview and is a SFO airline technician, leaned over and picked up a bottle of water. “I’ve been coming here two times a week since 1987,” he said. “It fits in with my work schedule.”

Wearing purple Riordan High School Crusader sweatshirts, three teenagers walked to an unused backboard, while Sean Johnson sat out, waiting his turn to take the court. “If there’s any trouble,” he said, rustling up a ball, “we tell the dude to take it someplace else.”

By 3 p.m., 23 players were shooting hoops on seven courts. The gym door was propped open. A breeze circulated, cooling down several of the shirtless players who sat in its doorway. “Who’s up?” asked Porter, looking toward the chalkboard.

Six more players took positions on the half-court, each selecting a player to guard. An offensive player bounced the ball in bounds and the players began to pick and roll, slicing back and forth, dribbling and passing, shooting and rebounding. They followed the time-old ritual, promulgated by decades of playground custom, where the team that made the shot takes the ball out and the winning team holds the court.

The ebb and flow of neighborhood basketball continued, as it has done for generations in Glen Park. Rosas watched. While he’s challenged by a building in need of a systemic repair, he puts the best spin on matters. “Our location is gorgeous,” he said, “and I have some wonderful people to work with.”

Matt Hill, 33, entered the gym. Raised on Mt. Davidson, Hill spent his youth as an Eagle Scout and his summers at Silver Tree Day Camp. He hiked the Sierras with his Boy Scout leader father and his older brother and played organized youth basketball. Now married and a father of two sons, he’s been coming to the gym since 2001 to test his mettle, a rite of passage that wouldn’t be foreign to Bart Borg.

“In order to compete,” he said, thinking about players such as Terry and Williams, “the burden of skill is on me.” Hill arrives at the gym after work twice a week, and he comes as much for the camaraderie as he does for the competition. “Vince is a heck of a guy,” he said. “I come to see guys like him as much as I do for the exercise.”

The days when the cash-strapped Rec and Parks Department offers free access to playground basketball courts may soon be over. Pay-for-play may become the name of the game in what has been tax-supported public places.

“The guys have talked about it,” said Hill. “I’d pay, but the costs would prohibit others from continuing to exercise.” Exercise would not be the only loss. A civic space that translates into community civility would be lost, as well, and not simply for Hill and his contemporaries.

“It’s pretty cool to see some of the guys bringing their kids here,” Hill said. Devall Porter walked over, ready to defend his team’s victory. The airline mechanic smiled: “I’m thinking of bringing my 13-year-old daughter over from Richmond to play a game of HORSE.”

All photos by Murray Schneider