One of the last times Lisa Wayne dug into Glen Park soil was on January 11, 2020, a month before COVID-19 changed everything.

With her teenage son, Isaac, Wayne planted dozens of drought-tolerant plants and shrubs such as gooseberry and red flowering currant at Fairmount Plaza, a postage-stamp oasis nestled between Diamond Heights and Fairmount Heights.

Now, nearly two years later, Wayne leaves a job she has held since 1997 as San Francisco’s Recreation and Park Natural Areas Manager, responsible for 31 natural areas within the city.

She’s departing to work for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission where she’ll become land and watershed manager for the Crystal Springs Watershed.

You know the area, though you may not realize it. As you drive south on I-280 it’s the pristine stretch of greenery and water you pass about 25 minutes south of Glen Park. It consists of two artificial lakes that store some of San Francisco’s water in the rift valley created by the San Andreas Fault just to the west of Burlingame and Hillsborough.

Wayne will be responsible for the management of 23,000 acres or land and 50 staff that include foresters, arborists, and biologists.

She starts November 1.

While Wayne will be gone from Glen Canyon, she’ll now become one of the reasons when Glen Park residents turn on the tap they’ll get fresh, cool, wonderful-tasting Hetch Hetchy water.

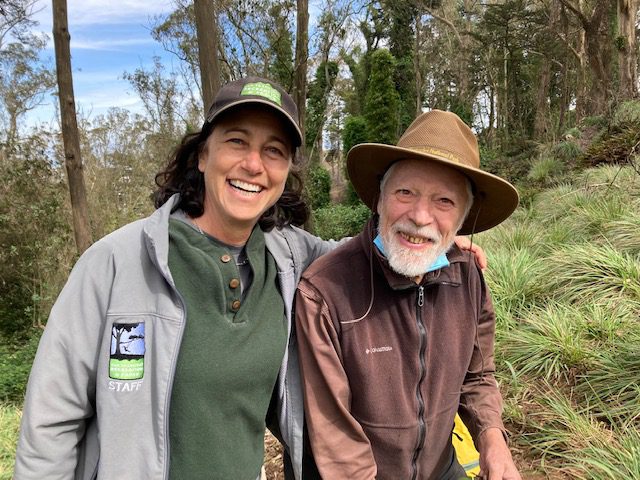

Wayne will be missed by those in the know, but her departure has not gone missing. Jake Sigg, a San Francisco naturalist, kicked off his September 29, 2021 newsletter with the following headline:

“A loss for San Francisco’s Natural Resources Division, a gift to watershed management.”

Sigg, who spent a legendary career as a gardener and supervisor for the Recreation and Park Department and continues as a heavy lifter with the California Native Plant Society, continued, “Although this is a serious setback for the severely understaffed NRD,” he penned, “from a larger perspective, it can only be considered good news. The watershed is a priceless refuge, and Wayne’s tenure will mark the first time it has been managed by a trained ecologist.”

There isn’t a natural area in San Francisco that hasn’t benefited from Lisa Wayne’s expertise and stewardship, San Francisco Recreation and Park General Manager Phil Ginsburg told the Glen Park News.

“Under her guidance, we have established trails among ancient oaks, preserved numerous native species and provided more than two decades of education to the community on co-existing with urban wildlife. Lisa’s shoes will be nearly impossible to fill, but I take solace in knowing she will continue to enhance and protect the city’s natural resources in her new role with SFPUC.”

On September 28, I sat with Wayne on a bench in the Inner Sunset in front of Arizmendi Bakery on Ninth Avenue. She’d driven from her Stanyan Street office. We’d arranged to catch up before she departed Rec and Park on October 12. I met Wayne in 2007 when I began volunteering on Wednesday mornings with Friends of Glen Canyon Park. The Friends mission is to assist stewarding, restoring and managing Glen Canyon’s 70 acres.

Wearing a similar outfit she’d had when she and her son bent their backs over one of the 900 shrubs planted at Fairmount Plaza 22 months earlier, Wayne reminded me she’d grown up in Southern California, earned a BA in Political Science from the University of California Santa Barbara, and, in 1995, a MA in Conservation Biology from San Francisco State University.

Afterward, she took a position with an environmental consulting firm, then as an adjunct biology lecturer at College of San Mateo and San Francisco State University.

“You’ve been at NRD for a few months shy of 25 years, why the change now?” I asked.

“It’s been a long time,” she answered. “but I’m offered a new opportunity that showcases a beautiful landscape on a different scale and order of magnitude than I’ve had.”

Crystal Springs mountain lions can make Glen Canyon coyotes seem almost domesticated, which, of course Wayne would instruct, isn’t the case.

“What will be the biggest challenge you’ll face?”

Pausing a moment to sip from her iced tea, she responded about being a new hire at the SFPUC, which oversees San Francisco’s sewer, power and water.

“Building a team with all my new staff,” she answered. “Encouraging trust and promoting teamwork.”

For nearly a quarter of a century, Wayne has been doing exactly that at Recreation and Park’s Natural Areas Program. While she was teaching college students at San Francisco State, ecologically minded San Franciscans lobbied City’s power brokers to establish a corps of naturalists that would include arborists and botanists. This cadre of university-trained experts were tasked with the management of unblemished City Franciscan wildland remnants, not unlike what California does with its Sierra Nevada wilderness.

It was during this time, in the late 1990s, that Wayne solidified her relationship with Jake Sigg. Sigg and other blue-ribbon environmentalists didn’t allow any grass to grow under their boots.

As a result, the Natural Resources Management Plan (NRMP) was fashioned and the NAP birthed, dedicated to preserving Glen Park-centric areas such as Glen Canyon, Twin Peaks, Mount Davidson, Billy Goat Hill, Dorothy Erskine Park and Fairmount Plaza.

With a respect for John Muir and a reverence for Aldo Leopold’s seminal A Sand County Almanac, Wayne was a natural to lead the Natural Areas Program, subsequently rebranded the Natural Resources Division.

I asked Wayne what her favorite California outdoor experience is.

“That’s a hard one because California is full of amazing ecosystems,” she responded. “But if I had to pick one it would be in the high elevation Sierra Nevada meadows during summer blooms.”

“Accomplishments?” I asked the woman who in 2014 had been honored with a SPUR Good Government Award,

“Well, first, I’d say just building the NAP from scratch,” she answered. “Fashioning trails, for instance.”

Well before the new and noteworthy pre-pandemic Crossover Trail came online, Wayne had overseen Glen Canyon’s 1.8-mile moderate Creeks to Peaks Trail that witnessed box steps and stringer steps facilitate easy promenades through Glen Park’s natural area, again enjoyed by throngs of day hikers as the delta variant wanes. In 2015, she hosted several evening public meetings at Silver Tree Day Camp that solicited public input, but even more to the point, when it came down to doing trail-building she laid down her administrative pen and laced up her work boots and personally surveyed paths, placing her imprimatur on their grade, composition, rock and willow bough placement.

“I’m proud of the Phil Arnold Trail in Golden Gate Park, too,” she offered. “And the successfully rescued Twin Peaks Mission Blue Butterfly and the Sharps Park Red-legged frog and the garter snake.”

Mostly, though, she’s at peace with the concept of wildlife management that is undergirded by a mantra of humans living in harmony with nature, where no monoculture of invasive weeds is allowed to intrude upon original habitat, and where timed-out and toppling trees are so sacrosanct that they are allowed to remain in spaces such as Berryessa Creek Park in San Jose where a 70-foot tall eucalyptus tree fell and killed a man in February 2016.

In a voice channeling Aldo Leopold, who was instrumental in reintroducing wolves into woodlands that had a salutary impact on forestry ecosystems, she offered her unapologetic take on coyotes that have become omnipresent in Glen Canyon during her tenure.

“It’s easy to understand some views,” she said, “and we still have a way to go in our coordinated response to these animals.”

While coyotes, which once had federal government bounties on their heads, present a threat to ranchers and sheepherders, Glen Canyon walkers are cautioned to share space and not habituate the animals by offering them food, and dog walkers are advised to keep their canine companions leashed.

Besides, living in union with these animals has a law of intended consequence on our urbanite ecosystem.

“The coyote’s main diet,” volunteered Wayne, “include gophers and mice.”

Over the last decade, I’d occasionally worked shoulder-to-shoulder with Wayne, pulling weeds on Glen Canyon’s eastern slope, where we immersed ourselves in rocky grasses and scrubland. I’d welcomed her tutorials as to the difference in look between poison oak and English ivy and how to distinguish California blackberry from the Himalayan variety. While she’d uncomplainingly pull on Wellingtons and slog ankle deep in Islais Creek and clear detritus, she’d smile when I showed a preference for wielding a lopper and clear trails of less laborious overhanging Arroyo willow.

What we shared, though, is a respect for the rustic sanctuary Glen Canyon affords in one of the densest cities in the United States.

Over a decade ago, in February 2011 during one of Wayne’s work party visits to Glen Canyon, accompanied by her son, I’d taken a photograph them.

She reminded me of it in an email a few days before our Inner Sunset visit.

“I will always treasure the photo you took of Isaac holding up my badge,” she messaged, “where he seems to be saying ‘pay attention to my mom.’”

Luckily, we all have paid attention to her for a quarter of a century.

“The move is bittersweet for me,” Wayne shared in a September 20 email. “It’s truly an extraordinary opportunity for me professionally, but I love San Francisco’s urban nature, my team and our volunteers. I will miss all of it.”

Her new job imminent, she made one final visit to Glen Canyon on October 12, her last day on the Rec and Park clock.

For one month, under her supervision, Islais Creek had been daylighted north of Silver Tree Day Camp by her corps of naturalists. Now one can stand on the east bank and look across the creek with an unimpeded view. From September 12 crews of NRD gardeners, for a dozen days, had pruned willow, cut back Himalayan blackberry and pulled English ivy from the creek and its banks. Left untouched after the 20-month pandemic, the invasives would have thwarted the fast running of the creek after winter rains and smother underlying insect sustenance for flocks of native and migratory birds that find harbor in trees during nesting season.

Characteristically, Wayne didn’t remain idle as she bid her team farewell. Donning protective gear, she requested a chainsaw and wielded it in the service of cutting through hazardous and horizontal willow limbs that menaced recreational users.

Four days later, on September 16 – supervised by NRD gardener Isao Kaji and while Lisa Wayne holidayed in Utah wilderness preparatory to reporting to November SFPUC duty – a corps of 10 Friends of Glen Park volunteers worked for nearly three hours bagging ivy and willow branches, then placing them along an eastern slope where they will slowly turn into compost. Eventually, drought tolerant and habitat friendly snowberry, iris, columbine and fern will be planted creek side and take root in its riparian environment.

I’m looking forward to looking up Lisa Wayne after she’s had a year or so to dig into San Mateo soil, surrounded by Crystal Springs old growth Douglas-firs, chaparrals, oaks and madrones, and where Aldo Leopold’s vision of bio-diversity stewardship is modeled alongside water and wildlife conservation and range and watershed management.

Before I could ask a final question, Lisa Wayne pre-empted me.

“I’m not running away from anything,” she told me. “I’m moving towards something.”