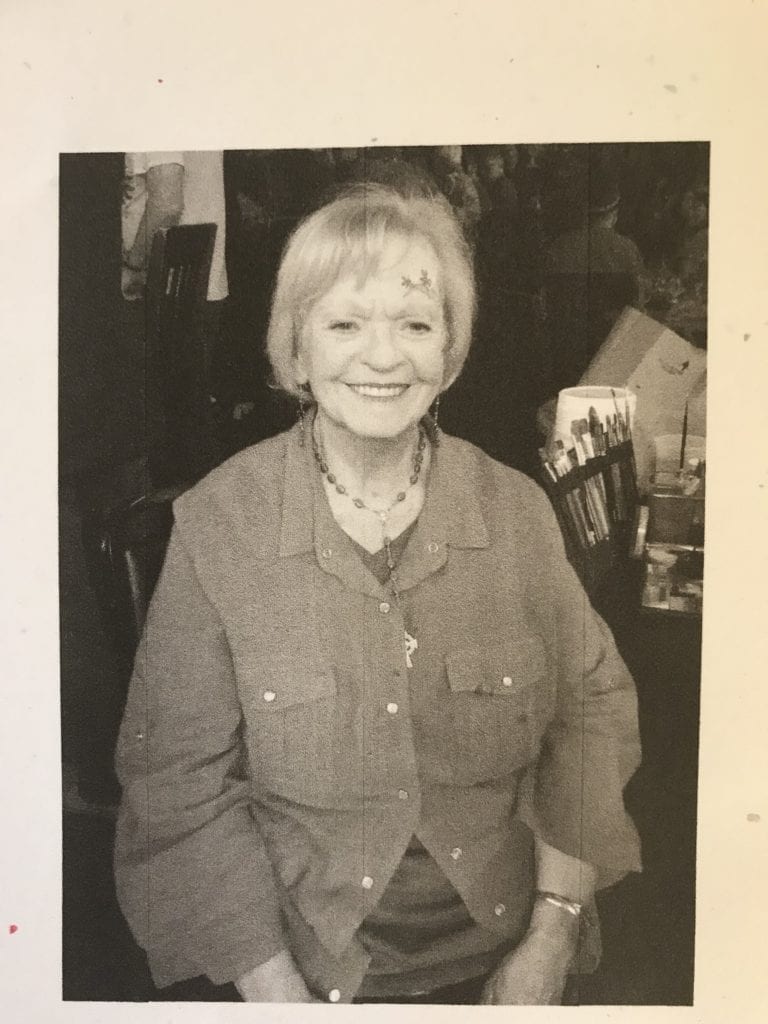

Glen Park lost a Mission High School old girl on June 12.

Glen Park lost a Mission High School old girl on June 12.

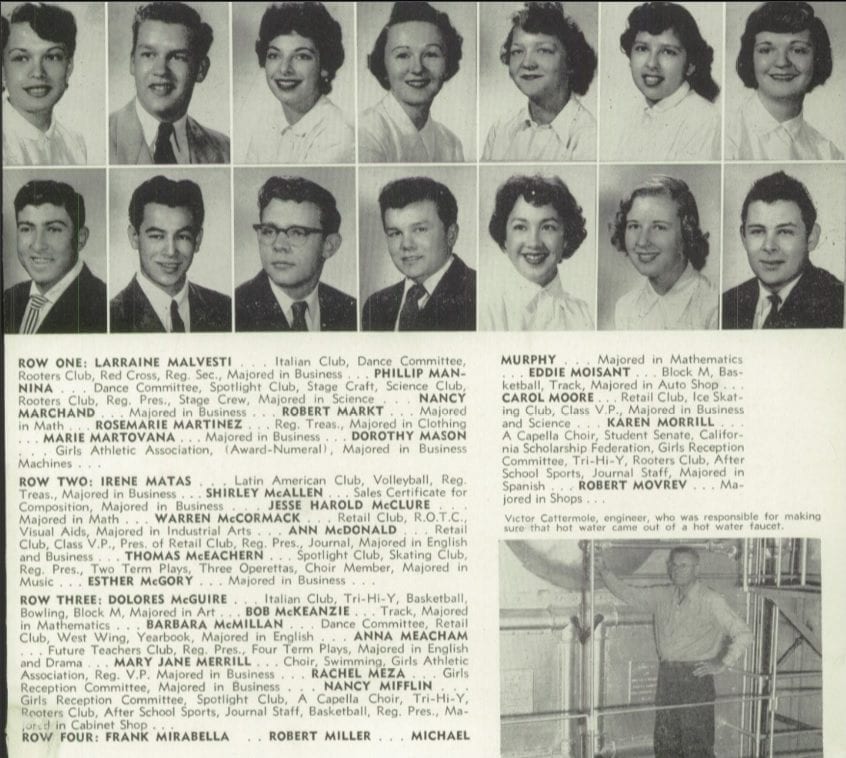

Nancy Mifflin Keane, who lived in the heart of the village, graduated from Mission, Class of 1954.

On June 22, Keane’s daughter, Theresa Keane-Lama, sat in her Diamond Street home and reminisced about her mother, who was born in Noe Valley on July 9, 1936, one of nine sisters.

The Keane house fronts Diamond Street, and is only a few doors up the hill from the Manzoni Restaurant. Its back entrance faces Thor Avenue.

“My mom preferred that my sister Christine and I enter the house from Thor,” said Keane-Lama. “It was easier coming home from elementary school.”

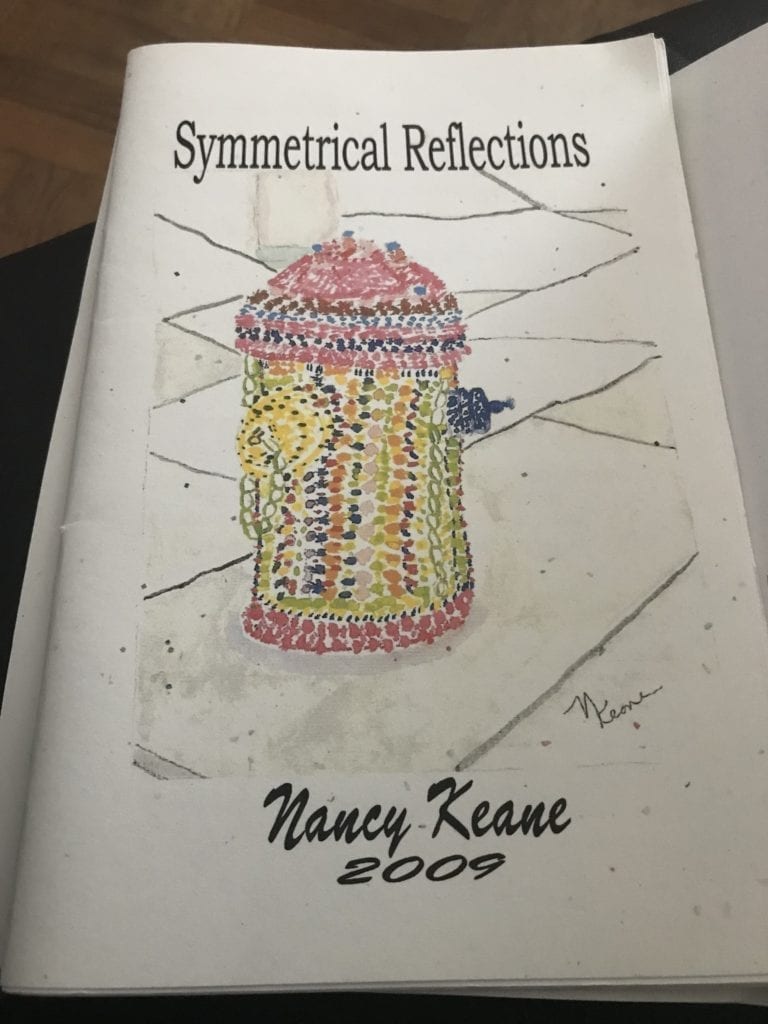

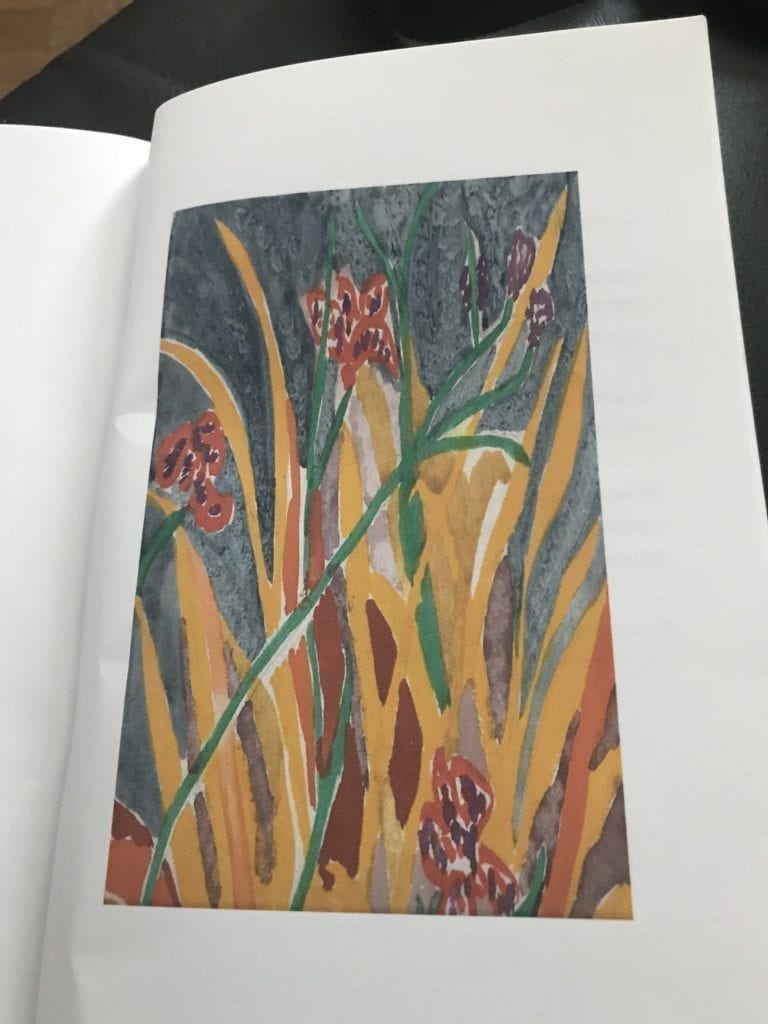

Nancy Keane doubled as an active parent at St. John The Evangelist school. There she coordinated fund raisers and chauffeured children around the city while working into the 1990s at Wells Fargo Bank. Earlier, she’d attended San Francisco State University and when parenting permitted she’d write poetry, paint watercolors, take Europe sojourns, and delight relatives with family lore, gilded with bits of Celtic blarney.

Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “There are no second acts in American lives,” but Nancy Keane’s life would belie such a notion. After losing her husband, Jack, whom she met at the Russian River and married in 1957, Nancy turned her attention in 1990 to running the family saloon, the 3300 Club at 29th and Mission Streets.

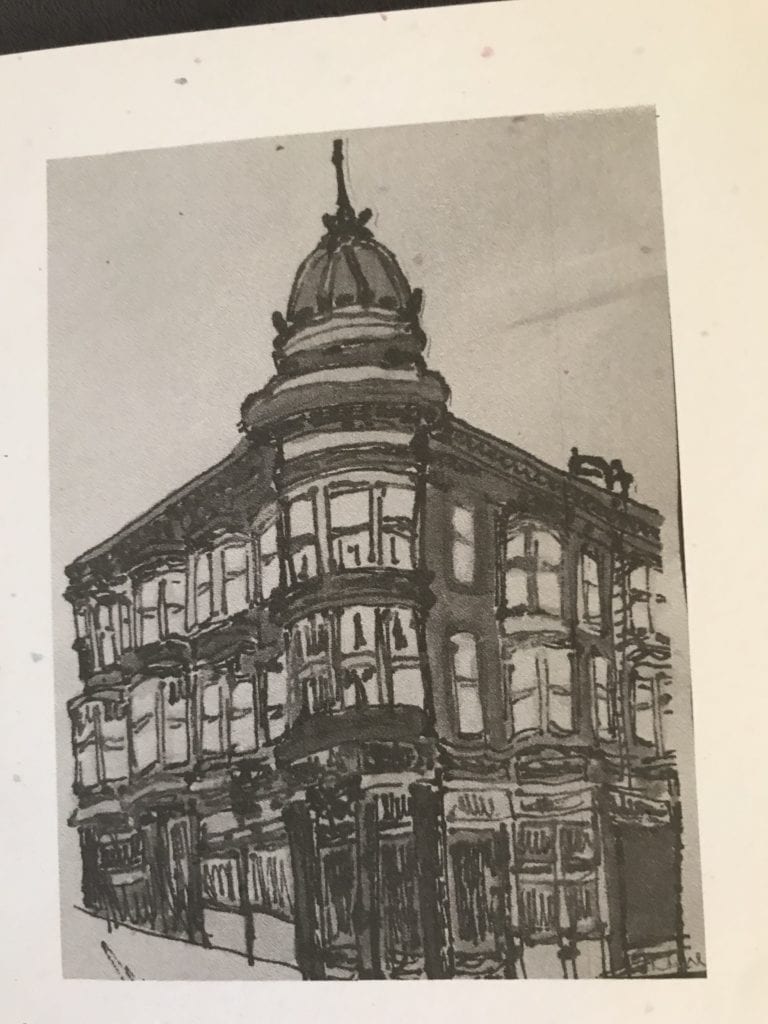

The Keane tavern, housed below the Graywood Hotel and next to Cole Hardware, had been a Bernal Heights fixture for 60 years when it burned on June 12, 2016, a causality of a four-alarm fire that left 58 SRO hotel tenants homeless.

“My dad opened the bar in 1956,” recalled Keane-Lama, “and it remained open year-round except for Election Day and my father’s funeral.”

The 3300 Club was a facsimile of the East Village’s McSorely’s Old Ale House. The two licensed public houses — Manhattan’s McSorely’s established in 1854 and San Francisco’s 3300 Club in 1956 — were similar. Each was rickety, quirky. Neither could be confused with a Barbary Coast or Bowery gin mill. Neither catered to patrons likely to become victims of Shanghaiing. Both were genuine public houses, each occasionally experiencing shenanigans the result of customers missing the last call.

The Keane watering hole attracted a ragtag tangle of working stiffs who’d routinely stake out bar chairs, then nurse drinks while watching sports on wall mounted television screens. Some customers hunkered in solitude over a pulled pint of Guinness, while others gathered in banter over social drinks, while still others shared tables beneath a 29th Street window and strategized progressive Bernal politics.

Customers attempted not to notice bartenders, drawing mugs of beer with one hand while grappling with one of the five TVs that went on the fritz with the other hand. In aggregate, the 3300 Club demographic was not unlike that of the Glen Park Station, chummy regulars hoisting a few after a shift at PG&E or pols escaping City Hall for a well-earned pint of bitter.

“The tavern could probably be called a dive bar,” said Keane-Lama. “It wasn’t pretentious, wasn’t fancy, and certainly wasn’t gentrified. It had wobbly chairs and an ice machine that never worked.”

“Warren Hinckle and his dog were regulars,” she added, about the late muckraking newspaperman and his Bassett Hound, Bentley.

After Jack’s death, Nancy Keane, during her productive second act, attempted to bring a little refinement to the joint while simultaneously burnishing her poetic chops.

“My mom started poetry sessions, as well as bringing in an Irish band on St. Patrick’s Day,” said Keane-Lama. “The readings occurred every month, on Tuesdays, but never on Fridays and Saturdays when they’d have killed business. My mom’s open mic was the only time some of these poets had an opportunity to read in public.”

The tavern veterans weren’t initially fans, preferring to save their hurrahs for pinch hits not poems, more interested in a double play than a single stanza of verse.

“Nancy was tickled and impressed with her poetry sessions,” said Eric Whittington, owner of Bird & Beckett Books and Records. Whittington has hosted Geri DeGiorno, Keane’s sister and former Sonoma County poet laureate, at his bookstore’s poetry slams. “But eventually the regulars stopped groaning and became charmed.”

Nancy Keane’s customers were a hodgepodge, and given her sense of inclusivity, she embraced her colorful habitués’ moaning eclecticism.

“There were characters for sure,” said Keane-Lama. “Fritzy, for one. He painted murals on the 29th Street walls, ocean scenes that included whales and deep sea fish.”

But Fritzy’s piece de resistance was found indoors, a rendering that anointed the dry wall above the men’s pissoir.

“Fritzy painted a voluptuous Ruebenesque nude over the men’s urinal,” said Keane-Lama. “My dad wouldn’t have stood for it, but my mother loved it.”

Fritzy wasn’t without his idiosyncratic peers in an establishment rife with eccentricity, many a 3300 odd fellow boasting a Falstaffian back story that rivaled any of those recounted in Joseph Mitchell’s “McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon.”

“Everyone had nicknames,” said Keane-Lama. “There was Trapper and Connie the Baker. There was Werewolf and Dirty Eddy, Sharky, Ed the Fed and Budweiser the Plumber.”

Arguably, however, Howie was the standout since he was rarely encouraged inside. Decamping from a south-of-the-slot flophouse, Howie undoubtedly was on the waiting list of the SRO above the 3300 Club. While he cooled his heels, he took up residence atop the fire fighters’ street corner go-to fire plug.

Howie became Nancy Keane’s muse, as her poem, “Howie’s Post,” would have it.

Howie’s post is the fire hydrant outside Jack Keane’s bar.

He stands on it, sits on it,

Swings his sword at motorists

And passersby, his mouth never stopping.

He visits Safeway in his trench coat, filling his pockets with filet mignons,

Selling them on his corner to any willing buyer.

Howie only takes the best.

When Howie died, no one took his place!

Always a classy lady, Keane glossed over Howie purloining the tenderloin.

Fernando Aguilar, a Bernal Heights resident, bears witness to the saloon’s Scaramouche-like ambience, frequently partaking of the Keane establishment’s frothy libations.

On June 21, he sat at Bernal’s Emmy’s Spaghetti Shack on Mission Street.

“I like bar culture and I’d drop by the 33 twice a week around 4 o’clock,” said Aguilar, who lives on Elsie Street. “It was dusty, the jukebox was not updated, and the ice machine was the worst in town, but the regulars loved it. I knew I’d always find a friend there.”

“It was like a community center for adults, but adults who drink,” he continued, while spearing a meatball the size of a small boulder. “There were retired lawyers sitting next to low riders, sitting next to journalists. It was a hole-in-the wall dive, but that’s what gave it its charm. Everybody was welcome.”

Theresa Keane-Lama would find no difficulty subscribing to such an assessment.

“After my dad died, my mother would make corn beef and cabbage for St. Paddy’s Day and tuna fish sandwiches for her poetry gatherings,” she said. “The customers were like family. There was a guy, a veteran, who had no relatives we knew of. My dad would drive him to the VA hospital, and when he eventually had to go into an assisted living facility the customers rallied and helped him make arrangements.”

The saloon veterans showed their generosity in other tangible ways, as well.

“Customers would bring in food, prepared in crock pots,” said Keane-Lama, “and when my mom needed a new television, the regulars chipped in and bought one for the bar.”

Fernando Aguilar shared just such a Capraesque caper, a scene left on the cutting room floor of “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

“I’m sitting in my usual spot, in front of the bar, and hear a crash,” said Aguilar, a McAteer graduate. “I get up, go outside and see a regular, a retired patent lawyer on the pavement. He’s lying next to his bike where he’d collided into a car. On the ground, he’s rummaging around. ‘I lost my tooth,’ he says. So the guys hop off their stools and help him find it!”

On the other side of Thor Avenue, Nancy Keane’s neighbors verified much of this bromance-both-sides-of-the-bar philanthropy. For years the couple observed the Diamond Street house perform as an industrial kitchen for Keane-public house comfort food, as well as a Keane-household mecca of neighborhood hospitality.

“Every holiday I’d see Nancy filling her car with food,” said Vicki Saltzer-Lamb, a social worker. “She’d take it to the bar, where she’d embrace everyone from the mayor to down-and-outers.”

“That’s true,” echoed Jacqueline Saltzer-Lamb, a communication director for Kaiser Permanente. “Nancy was so kind. Both the house and her bar were like a ‘Honeycomb Hideout.”

Nancy Keane authored another poem on August 23, 2016, two months after her bar went ablaze, calling it “3300 Mission Street – 1897 to 2016.”

It’s an ode to an ale house worthy of both Old John McSorley, his son Bill McSorley — two Irish barkeeps extraordinaire — and to saloon keeper, Jack Keane

The poem’s a reverie to an epoch we’ll not soon see the likes of again.

The year is 1956.

Gleaming mahogany walls join plush carpeted stairs reaching toward stained glass ceiling and lobby of the Gravewood Hotel.

Fritzy and Connie the Baker exit the hotel followed by two men wearing Homburg hats and vested wool suits with white carnations in the lapels, a lasting tribute to Mayor Sunny Jim Rolph.

The four men pass beneath 3300 Club neon. It is 6:00 a.m., and this neighborhood bar is rapidly reaching capacity.

An inviting aroma of strong coffee, freshly baked strudel, and distilled spirits floats upwards to high Victorian ceilings.

Jitneys line up outside 29th Street. Shop girls bump knees with politicians as jitneys move towards City Hall.

Big, burly union workers tip their hats to nuns passing in front of the 33 on their way to St. Paul’s Church.

Inside the 33, Merchant Seaman, Trapper Jack and Bricklayer Johnny McCaffrey borrow money to pay their union dues.

Mario Scardena needs a couple of hundred in cash to bring his new Sicilian bride and baby boy home from St. Luke’s Hospital.

This generosity and true sense of community would forever exist in the 3300 Club.

Chick Rowan inspects racing form, while the Professor and Ed the Fed play a game of chess. Johnny Foley serenades them with an ancient Irish song.

Inclusive warmth of the 3300 Club morphs with Mission District sunshine in this ‘City by the Bay.’

“My mother was truly a Renaissance woman,” summed up Theresa Keane-Lama. “She was a banker and a bartender, a poet and an artist in between and ever after.”

Nancy Keane didn’t have a long third Act. She passed exactly two-years-and-four days after the loss of her bar, which three generations of the Keane family had worked behind.

She entered the hospital ER for the first time in January and by mid-May found both comfort and care at the Jewish Home on Silver Avenue. From there, she transitioned to hospice assistance in her Diamond Street house with her Thor Avenue backyard.

The loss of her saloon may have knocked some of the wind from her sails, some venture, but it didn’t diminish her adoration for writing, as she wished donations in her memory be made to 826 Valencia, a non-profit dedicated to helping children and young adults develop writing skills and to assisting public school teachers who’d been such a help to her.

Mission High School has an 826 Valencia writing room. On the third floor, the room is clubby. Its walls are lined with books and dictionaries. Tables are filled with pencils and pens.

Here young authors write alone or collaboratively.

Two floors below, outside principal Eric Guthertz’s office, along corridor walls hang photos of most Mission graduating classes, stretching back to the early 1920s.

Nancy Mifflin Keane’s Spring Class of 1954 class photo is missing, but not the photo of the Fall Class of that year.

In it, the twelfth graders look fresh-faced. Soon they’d walk across a stage and accept their diplomas.

That year, 1954, Nancy Mifflin learned about rhymes, couplets and sonnets.

That’s what senior English is all about, isn’t it?

That June, that summer of her youth, the first Act of her play was still unfolding, waiting for her to put pen-to-paper.

She’d have time.