Story and photos by Murray Schneider

Mary Huizinga can add her name to a growing list.

Glen Park has had its share of artists over the years. Sussex Street’s Bruce and Jean Conner’s work has appeared at Bird & Beckett and hung in neighborhood coffee shops; Michael Waldstein’s photos have graced the walls of a gallery across from his Chenery Street home and Chenery Street’s Ellen Rosenthal’s photos have appeared at Higher Grounds.

Now Huizinga, a 30-year Laidley Street resident, joins their ranks.

Huizinga has been fascinated with letterpress printing since she first enrolled in a trio of City College of San Francisco art classes in 1997, the year she retired as a computer programmer.

“I initially took an etching class,” she said on a recent Friday. “Then I gravitated to letterpress.”

She’s never looked back, except for having to glance backward at a printer’s composing stick, which on a chilly December afternoon held three rows of type ready to place into her Vandercook letterpress printer.

“To set type you have to read left to right and upside down,” she explained, as she fingered the type, which would inscribe 40 personalized Christmas cards.

Letterpress involves taking movable type and painstakingly putting it into a composing stick and then its imposition into a press bed. Johannes Gutenberg perfected the process in the mid-15th century and it’s stayed in vogue for 450 years until off set printing usurped it.

A member of the Graphic Arts Workshop, a Dogpatch printing collaborative located in the American Industrial Center building between 22nd and 23rd Streets, Huizinga stood beside her letterpress printer ready to begin. The cavernous studio, all 2,000 square feet of it, felt cold. She dressed warmly, donning a knit cap, a long sleeved shirt, and a sleeveless sweatshirt. No stranger to printer’s ink, she wore a Rorschach-stained apron over it all.

“We average 30-40 members here and working space is never an issue,” she said. “The cooperative is open twenty-four-seven and I can work at my own leisure.”

The GAW has provided Bay Area artists with affordable access to printmaking facilities for almost 50 years, tracing it roots back five decades to the California Labor School. Its original members printed posters, leaflets and pamphlets in support of peace and civil rights issues.

During the Sixties it lent its space for anti-Vietnam War activities. In an egalitarian spirit, management of the Workshop is conducted by a board of directors, which is elected from and by its 40 members. The Workshops cooperative culture is based on a few simple common sense rules: Be safe, be clean, be courteous and share the chores.

Surrounded by etching presses and additional equipment needed to produce monochrome and color lithographs, Huizinga busied herself in preparation for a five-hour marathon at the workspace.

The GAW doesn’t simply take any artist who walks through its front door.

“I had to submit a portfolio of my work to the membership committee,” said Huizinga, now ready to begin typesetting.

She surveyed her space, finding no shortage of elbowroom. She sat before drawers of individual printer’s cuts and others drawers crowded with battalions of type. She selected a Geramond Italic font for her Vandercook and then maneuvered metal “furniture” to lock and load it in place, using a key for the task.

The letters spelled out her 16-word Yuletide message. Then she inked the letterpress rollers with Milori Blue oil ink, applying it with a putty knife. She turned the roller several times until the ink covered the space to her satisfaction.

“People are always interested in things not mass produced,” said Huizinga, who hails from Chicago and who was clearly not having a Hallmark moment. “Hand-crafting adds sentiment.”

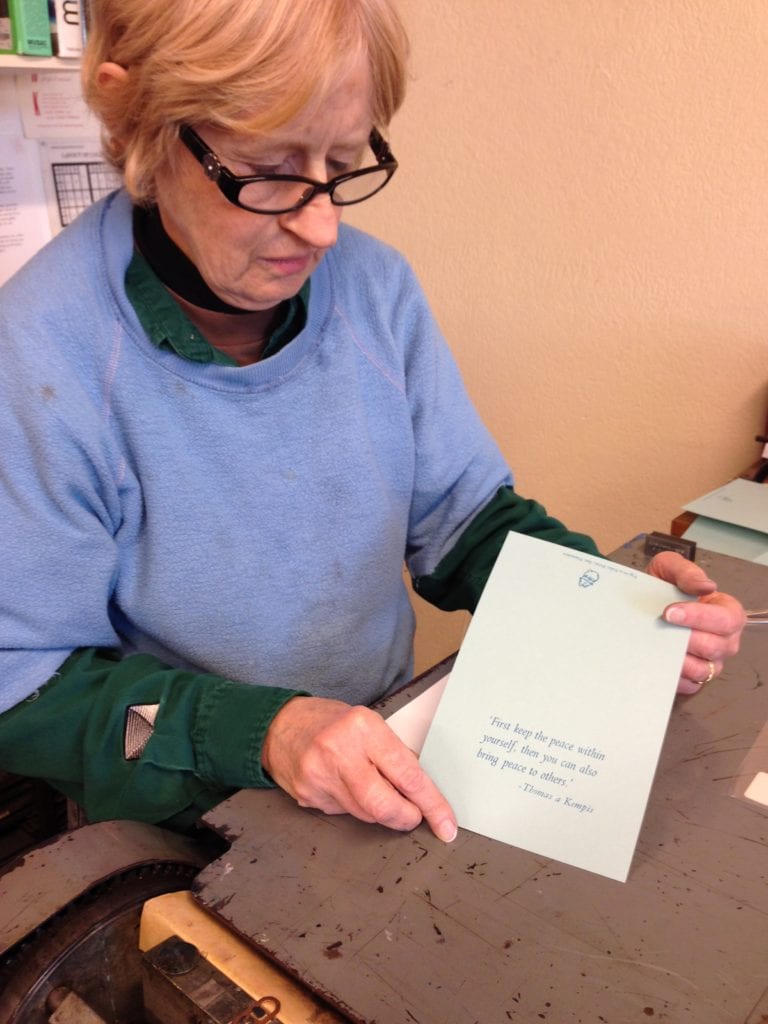

She cranked out a sample copy on five-and-a-half by eight-and-a-half inch blue stock.

Her limited edition ephemera read: “First keep the peace within yourself, then you can also bring peace to others.” A letter in Thomas a Kempis’ name appeared, insufficiently inked.

“See,” she pointed at the “m” in the Kempis’ first name. “The ink needs to be applied more uniformly.”

She anointed the roller with another light dab or two. She studied the print bed, as well. Next, she placed the paper stock on a hinged platen, securing it into position, and produced another sample.

“This is precision work,” Huizinga said, tweaking the inscription so it would appear evenly spaced on the card stock by adjusting several quoins, wedge-shaped blocks used to secure type in a frame or chase.

She measured the result with a pica pole, a hard-edged ruler.

Satisfied, she cranked out still another sample. Five artist cohorts had morphed around her. They each circled the spacious studio, one standing before a Sturges etching press while another labored over an etching.

When Mary Huizinga isn’t fashioning personalized note and holiday cards, she’s not idle. Until earlier this year when her pet Chow passed away, she walked Chester through the village, either shopping or on her way to Glen Canyon. She takes each Wednesday morning off to volunteer with Friends of Glen Canyon, keeping the 70-acre natural area free from evasive weeds that threaten habitat. Four times a year she delivers the Glen Park News to neighborhood homes. With her husband, Bob, she’s even dabbled in the art of wine making.

Satisfied that her preliminary efforts were up to standard, she broke for lunch. Dogpatch, once the home of swarming packs of dogs that feasted on meatpacking offal, is fast gentrifying, and on her way to a cafe she passed gourmet chocolate and ice cream shops, a paper binder, and a wine tasting room. The irony that letterpress is seeing a revival in an artisanal form, sandwiched among the burgeoning technology juggernaut that threatens to push rental space through the roof at the very building she’d just left isn’t lost on her.

“I call this the stealth place bakery no one can ever find it,” she said about Jolt ‘n Bold, which had no visible signage.

“In Glen Park I know every shopkeeper by first name,” she said, thinking of Joe Schuver, whose Destination Bakery’s confections rival anything on the shelves at Jolt ‘n Bolt and Rick Malouf at the Cheese Boutique.

While a T-line light rail trolled for passengers parallel to her, Huizinga walked back to her studio, past a trendy high tech gym, which once could have housed a tannery, blacksmith or butcher shop and now boasted scores of fit rock climbing devotees who practiced rappelling techniques on simulated “indoor” mountains.

Her own warm-up over, she now readied for the main event.

She checked all her Vandercook settings and fitted a blank card into place. Standing to the side of the printer, she arced an arm and executed a swift parabola. The finished card twirled from the roller near the printer bed. She inspected it and determined it passed muster. She walked it across the room and laid it on a counter. She repeated her efforts until she completed 39 additional cards. Each dried until she could reclaim them.

She wasn’t done, though.

“It’s a collaborative culture here. We clean up for the next person,” she said.

She removed the type from her composition stick and repositioned each letter in its tray. She found a tin of Crisco and scrubbed each roller, using paint thinner as well. In addition to paying her monthly GAW dues, her other Workshop costs include freshly laundered rags. She used one now, rubbing the rollers until they glistened a metallic gray. Next, she broke down the type “furniture” and returned the quoins and key to their proper places.

Finally, she put the press to bed, covering it with a blanket. She placed a card atop the cloth, reminding the next user not to eat or drink around the Vandercook.

Unannounced, a baker renting space in the building stepped into the workspace. He gifted a tray of freshly baked bagels, which he placed on the same bench that had held Huizinga’s Christmas cards. His company sells baked goods to grocery stores throughout the City. Huizinga and her cohorts hovered around the tray, bagging bagels for later.

‘You know they taught this in high schools,” said Mary Huizinga.

She wasn’t speaking of the art of bagel baking, but the craft of printmaking.

On the back of each one of her cards reads her patented logo: “Pig-in-a-Poke Press, San Francisco.” Beneath it appears an imprint of a piglet, worthy of A.A. Milne.

Mary Huizinga may want to soon reconsider this impression.

Her Christmas came early this year, you see. Only a few days after she crafted her high end Christmas cards, she adopted an orphaned Chinese Chow Chow from a Bay Area rescue service. She named Chester’s successor Monty.

Monty has already beaten a path to Critter Fritters for a biscuit or two, slurping down each with a drink of water from bowl found outside Canyon Market.

Any chance there’d be a canine facsimile of these images in her GAW printer’s cut drawer?

“I moved to Glen Park in 1983 and it’s like a real neighborhood here,” she said. “People really do care for one another.”

******

Readers can find out more about the Graphics Art Workshop by going online: www.graphicartsworkshop.org.