To celebrate the Glen Park Association Website turning ten years old, we are reposting some of our favorite stories from the last ten years.

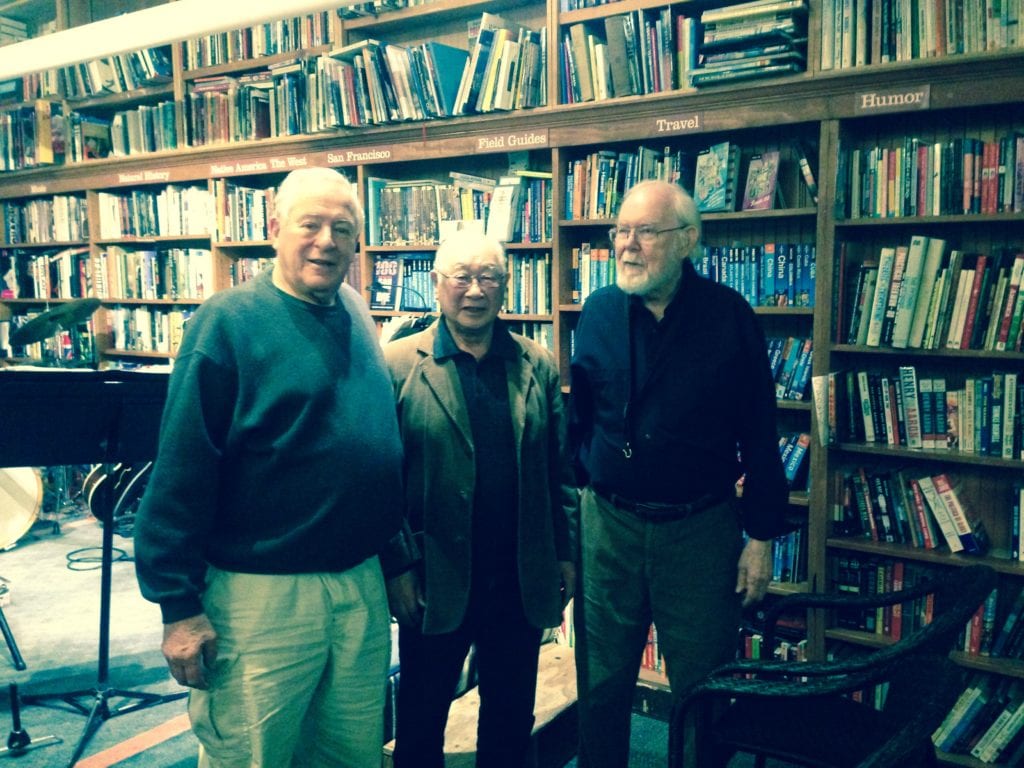

Howie Dudune, Ko Takemoto and Chuck Peterson. Ko Takemoto was a SFSU classmate of the late Dudune, a jazz saxophone player. He’d come to the Glen Park bookstore to listen to the Chuck Peterson band. — Bird & Beckett -March 26, 2015 Photo by Murray Schneider2017 marks the 75th anniversary of the United State’s forcible internment of Americans of Japanese descent into camps located in the U.S. interior where they were held until the end of World War II. The internment was ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

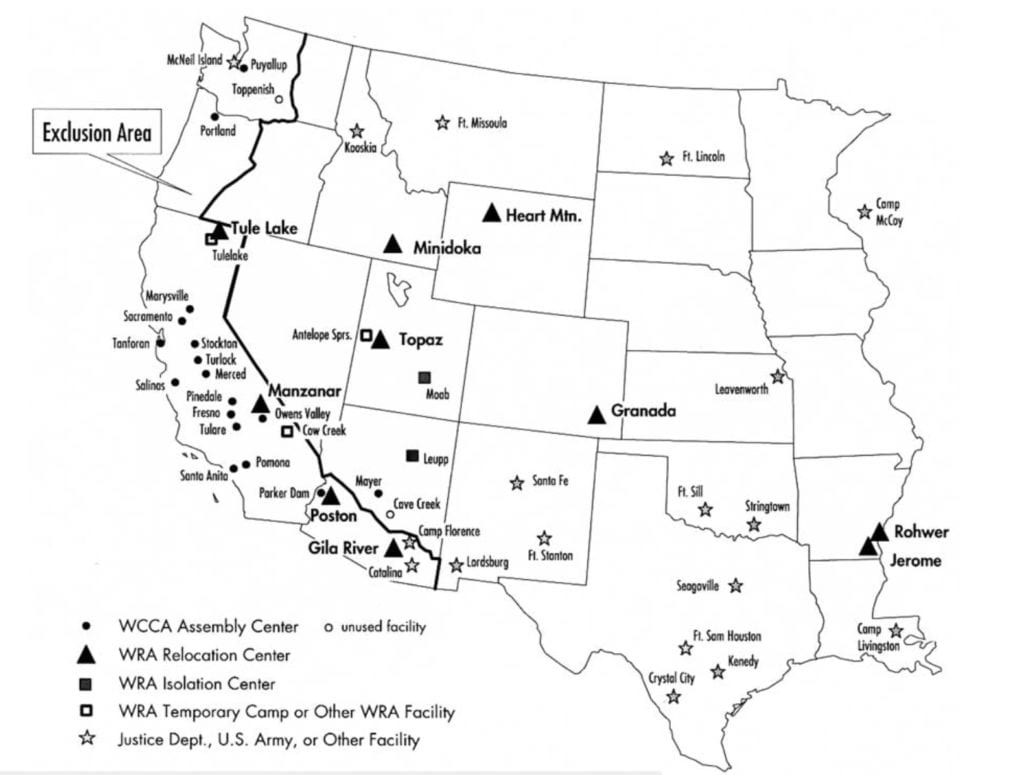

The order declared that anyone with Japanese ancestry was to be excluded from the West coast, which meant all of California and parts of Oregon, Washington and Arizona and sent to the camps. Almost 130,000 Americans were forced from their homes and into the camps in the spring of 1942. It is believed that more than 110,000 Americans were, 62% of whom were American citizens. Even people with just one Japanese great-great-grandparent were included in the exclusion, as were orphaned infants.

Steve Uchida and Ko Takemoto, two native-born Californians with connections to Glen Park, both have family histories stretching back to World War II Japanese American internment camps. On this the 75th anniversary of the removal of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, both men have done more than a little reflecting.

“My mother was born in the California and graduated from Alameda High School two years before the president issued his executive order,” said Steve Uchida, a Friends of Glen Canyon Park volunteer. “Even now she doesn’t like talking about it.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, two months after the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. With one stroke of the pen his edict led to Japanese Americans citizens and legal residents having to leave their homes with what they could carry and report to either to Santa Anita race track or San Bruno’s Tanforan race track.

Cramped horse stables, called “Assembly Centers,” served as temporary shelters until uprooted detainees could be transported inland.

Herded together, they awaited relocation to the interior where the government and public opinion believed they would no longer serve as security threats.

Uchida’s mother, Kiyoko, was sent to Heart Mountain, Wyoming; Ko Takemoto to Topaz, Utah

Kiyoko Uchida was born in Alameda in 1923 and Ko Takemoto was born in Santa Clara in 1934.

In the spring of 1942, Kiyoko Uchida was 19 and Ko Takemoto was eight-years-old. Both were Nisei, second generation Japanese Americans. Both were American citizens.

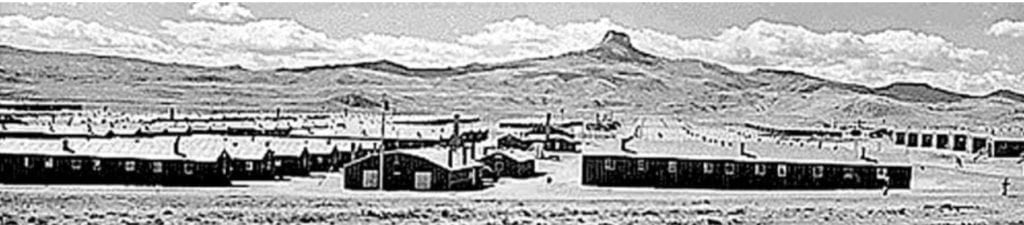

By the winter of 1942 both were incarcerated in desolate, crude and hastily built camps in the semi-arid deserts and the high plains in the center of the American West.

Today, Kiyoko Uchida is 94, one-month shy of her 95th birthday. This April, Steve Uchida, who delivered the Glen Park News four times a year to neighborhood homes on Bosworth Street and Stillings Avenue, moved from his Monterey Boulevard apartment where he’s lived across the street from BART for the last 15 years,

He’s returned to Pacific Grove where he was raised and where he will care for his mother.

By all accounts Kiyoko Uchida led a bobby-sox Santa Cruz adolescence.

“My mom spun Glenn Miller 78s and enjoyed listening to radio dramas such as “Inner Sanctum,”” said Uchida, who remains youthful and sinewy from playing tennis on Glen Canyon Park courts. “Gone with the Wind” was her favorite film, and in grammar school she’d haul stacks of books from the public library, which was only a block-and-a-half away.”

“After graduating high school,” Uchida continued, “she attended Armstrong Business School and trained to become a secretary.”

The Heart Mountain War Relocation Center, with all its attendant humiliations, interrupted all of this.

“In horrible situations when people lose their dignity they band together,” said Steve Uchida, a retired postal worker who worked as a mail handler at the U.S. Postal Service’s Processing and Distribution Center on Evans Street. “Like most people my mother made the most of a bad situation. Embarrassment, shame, even anger all factored in, and I’d image some people went crazy.”

Not so Kiyoko Uchida, nee Oba before her marriage to Kiyoshi Uchida.

“My mom made life long friends at Heart Mountain, and for years she and my dad drove to Disneyland to share reunions with the Murakami family,” said Uchida. “After the war, my parents moved on with their lives. They were proud to be able to afford a Buick. They’d take me, my brother and sister to Yosemite to hike and Niles Canyon to camp, even to San Francisco where they had season tickets to Kezar Stadium 49er games.”

Kiyoko Uchida was released from Heart Mountain in 1945, sponsored by the Cleveland Plain Dealer where she was hired as a secretary. While in Ohio she met her husband, Kiyoshi, who had just been mustered out of the U.S. Army.

“My father was a buddy of a guy whose girl friend was my mom’s second cousin and Cleveland roommate,” explained Uchida.

The young couple returned to Pacific Grove where they married in 1947. They honeymooned in Mexico, then began a dry cleaning business that today still thrives.

It fell to Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt from the Western Defense Command to facilitate the displacement of 5,000 plus San Franciscans of Japanese descent. De Witt worked from Building 35 in the Presidio, today home to the private Bay high school.

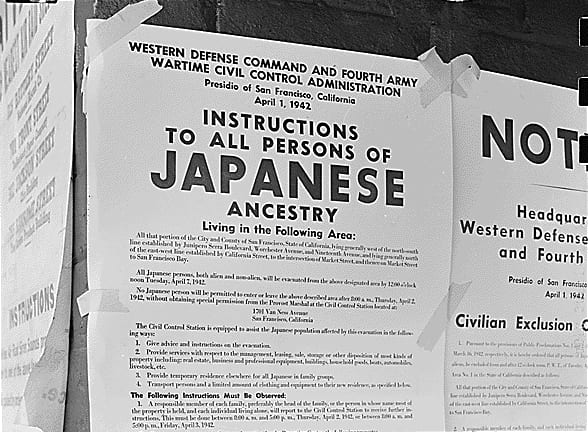

Empowered by the commander in chief, DeWitt issued one Civilian Exclusion Order after another, each one undergirded by the suspicion that racially-profiled American citizens and legal residents constituted a threat to neighborhoods such as the Sunset and Richmond Districts. While U.S Navy mine sweepers such as the U.S.S. Eider placed defense nets beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, DeWitt’s War Relocation Authority nailed signs onto Japantown telephone poles beginning on April 1, 1942, serving notice that residents must immediately abandon their homes and liquidate their businesses.

By the summer of 1942, 77,000 citizens, many of whom voted in the presidential election of 1940, and 43,000 legal or illegal resident aliens were removed at least 60 miles inland. If one were one-twelfth Japanese one could be rounded up, exiled to one of 10 internment camps strewn throughout the western United States and as far east as Arkansas.

Internees who refused to answer affirmatively to two War Relocation Authority questions, queries designed to obtain their willingness to serve in military combat and their readiness to swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America were imprisoned at the more secure Tule Lake Segregation Center.

Those who refused to respond correctly were labeled “No No Boys.”

Ko Tackemoto’s father, Kiso, wasn’t one of these defiant men.

Kiso Takemoto earned his living as a sharecropper on Stanford University property. With his wife, Inoyo, he grew strawberries. Kiso shared profits with the man who leased land from the Palo Alto university. The Takemoto postage-stamp garden, by 1941, was rooted west of the future Interstate 280, on the hills boarding Skyline Boulevard. American landowners had sought immigrant labor for fertile California farms as early as the 1890s, and on March 4, 1942 the San Francisco News reported “that nearly one hundred percent of all California strawberries were under the control of the Japanese.”

“My father would do odd jobs for the landlord, as well,” remembered Ko Takemoto, now a fit 82 years old, who routinely swims several times a week at the Embarcadero YMCA.

Kiso Takemoto, who emigrated to the United States in 1918, married Inoyo Tsurusaki and went on to have three more children, one of whom, Kei Takemoto, would join the United States Air Force after World War II and be discharged as a Staff Sergeant. Kei went on to become an airline mechanic and a lionized flight test engineer in the California aviation industry.

“Except for my mother who died in an accident a few months before Pearl Harbor, we all were sent to Topaz,” said Takemoto. “My mom was crossing a bridge built on university land. She was pushing a wheel barrow and fell off the bridge, hitting her head on a rock in the creek.”

At eight, Takemoto experienced another systemic change.

He was moved first to Tanforan and then several months later to Topaz, Utah where he remained until he was 11-years-old.

“At Tanforan they shoved us onto the race track. The horse stalls were already crammed with those who had earlier been displaced and the odor was terrible,” said Takemoto. “My father had to stuff newspapers into the cracks in the buildings to keep the wind out.”

Each was given a “tag,” as if each man, woman and child was a UPS package, then later sent by railroad to the Topaz War Relocation Center.

Once there the Takemoto family found a dry, wrinkled and windy wasteland where winter temperatures could descend to freezing and summer heat topped the high nineties.

“Again, sand blew through the cracks in hurriedly built tar-papered-barracks walls and covered everything,” said Takemoto, about buildings that had been sheet rocked by Japanese Americans already held in custody. Paid for their labor, the same internees erected four-foot barbed wife fences.

“Some people said we were at Topaz for our own protection,” said Takemoto, “but then why were the rifles pointed in, not out?”

As with the other exiles, the Takemoto family was held without trial, subject each day to the specter of guard towers manned by soldiers wielding weapons. On April 11, 1943, James Wakasa, who was 63, was shot to death by a guard for getting too close to the barbed-wire fence. Takemoto shared the compound with 8,000 others, placed in barracks that accommodated several families depending on their size. Each block had 10 barracks, a recreation hall, and a women’s and men’s latrine.

Privacy was at a premium, so Kiso Takemoto hung bed sheets to give the family a modicum of it. Furniture consisted of army cots, mattresses and blankets. Chairs and tables were constructed from scrap wood. There were two elementary schools and one combined junior and senior high school.

“We had pot-bellied coal stoves, so in the winter we could stay warm,” recalled Takemoto. “My memory is not what it once was, but the authorities brought in teachers for us, as well as using Japanese internees, and when my father seriously injured his eye chopping wood the military transported him to Salt Lake City for medical attention.”

If the ignominy expressed by those expelled from Bay Area homes manifested itself in mostly passive resignation and dignified stoicism, paradoxically but explicably some children had a different take. Kids can possess a curious restorative resilience.

“While I can only imagine what it was like as an adult,” said Takemoto, “as a child it didn’t bother me all that much.”

Eventually his minders, who Takemoto remember as not entering the compound that frequently, surrendered the charade of tight security. They abandoned their turrets and simply motored around the outside parameters of the camp.

“Playing in the guard towers was no problem,” recalled Takemoto. “Once in a while a jeep would come by and we would sit down and make believe we weren’t doing anything wrong. They knew what we were doing, but didn’t care.”

While radios and camera were forbidden, pretty much everything else was green-lighted, better to normalize the expulsion of innocent people who never presented a threat to anyone. By January 1943, 105 young men from Topaz volunteered for the military, serving with distinction in segregated Army units, allowed to serve their homeland only in the European theater. Such was the case with the 442nd infantry regimental combat team, the most highly decorated U.S. Army unit for its size and length of service in the history of American warfare. The men of the 442nd, mostly from Hawaii where the Japanese never experienced the diaspora, earned a significant number of Purple Hearts.

Ironically, some of these serviceman would return state side, in full uniform, and visit confined Topaz relatives who were permitted to take art classes, grow vegetables gardens, attend Sumo wrestling matches and dances, even obtain passes and ride a bus to Delta, the nearest Utah town where they could shop. By 1943, the government began encouraging those who had friends in the heartland to go and live with them, which explains Kiyoko Uchida’s move to Ohio. Internees could also attend college and obtain jobs as long as they didn’t return to the West Coast.

Ko Takemoto remained in Utah for another two years.

“I didn’t like baseball, which was very popular with the boys, but I enjoyed building model airplanes from scrap wood,” Takemoto volunteered about the Spitfire and B-29 planes he dashed off from cardboard and wood.

Boys being boys, Takemoto and his grade school friends pretended they were characters from movie adventure serials, cliff hangers they’d binge on during Saturday afternoon matinees.

Flash Gordon, armed with a ray gun, tangling with Ming the Merciless was common coin.

“We’d dismantle cot mattress frames constructed with hollowed metal tubes and make harmless paper darts, incapable of hurting anyone. We’d attach pads of these paper darts to our belts, pull one-out-at-a time and on-the-run blow them at each another. We got to be pretty good.”

Takemoto remembers his father, Kiso, pushing the envelope, as well.

“We wanted to assimilate as fast as we could, which is why even today I can’t speak Japanese well,” said Takemoto, “but my father really admired Samurai swords as works of art. He’d scrounge car springs, heat them in the camp boiler room furnace and pound different swords into shape.”

“You have to understand Japanese culture in regard to these swords. I don’t think the military would have approved of my father’s sword making, but guards rarely entered the camp area, as we were self governing.”

After VJ Day, Kiso Takemoto’s mechanical skills held the family members in good stead. The government transported them back to San Francisco where they took up residence in public housing at Candlestick Point, only a a few feet from the Bay. Always a fisherman, Kiso built a seven-and-one-half horsepower boat made from pontoons.

“We’d push it into the water, and my brother and I would fish for stripers and shiners,” said Takemoto.

Without their mother, Kiso Takemoto played a central role in the children’s lives. A landscape gardener, the elder Takemoto drove to the Peninsula each day, tending 1950s suburban gardens while his children attended City public schools.

Ko Takemoto went to Kate Kennedy and Cleveland Elementary Schools, Everett Junior High School and graduated Mission High School in 1953.

Capitalizing on a music gene he inherited from his father, who enjoyed playing the shakuhachi, a Japanese flute, Takemoto went on to attend San Francisco State University, majoring in music where he met the late Howie Dudune, a Bird & Beckett jazz saxophone player.

Hired by the San Francisco Unified School District in 1959, Takemoto went on to teach music to two generations of Glen Park, Sunnyside and Noe Valley teenagers at Herbert Hoover Middle School and Lowell High School.

“I had 90 students in my Hoover band class,” he said, “and parents would tell me how they wanted to enroll at Hoover because of its music program.”

He never strayed all that far from his own saxophone and clarinet, doubling down for decades during school breaks, hitting the road with a 15-member band, barnstorming throughout Northern California, performing for Japanese American audiences, often field workers such as his parents had been before the war.

“My Mission High friends formed a Japanese band, and for 40 years while I taught we’d climb into a Greyhound and entertain at Obon festivals,” said Takomoto. “We’d play as far away as Watsonville, Fresno and Bakersfield.”

Fittingly, the band honed their chops at San Francisco’s War Memorial Building.

After retirement, Takemoto rebooted his father’s makeshift boat, upgrading to a full-size fishing vessel, a Boston Whaler Conquest 21, which he sailed until recently beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, destined for the Pacific salmon runs along Stinson Beach.

“I think my education suffered at Topaz,” he said, without a trace of bitterness, “but I had a pretty good childhood and a good life.”

Married for 53 years, with three grown children, he looks back on 75 years and revels in one salient statistic. “Not one Japanese American” he said, “was ever found to be a spy or saboteur.”

In honor of his father, Takemoto donated to a San Bruno memorial for those held at Tanforan race track.

Preparatory to pulling up stakes in Glen Park, Steve Uchida believes it’s about memory, as well. Back with his mother now in John Steinbeck country, Uchida, has no trouble remembering and deconstructing. It’s really very simple for the retired United States postal employee. Where fences once locked people in, walls must not now lock people out.

“While they don’t exist physically any longer,” said Uchida, who has visited California’s Manzanar War Location Center when he’s hiked trails along Highway 395, “the blueprints for camps such as Heart Mountain still exist, potentially to be used against the ‘enemy’ by virtue of their national lineage, religion or skin color,”

The father of two children, the grandfather of four grandchildren, and the son of Kiyoko Uchida, Steve Uchida couldn’t be clearer about the take away.

“I think Japanese Americans should be among the first to stand up and support Arab Americans who may face or soon could the form of repression and discrimination we did.”

Steve Uchida is 69-years old now.

“When Americans see or read about these internment camps, I think they should not be saying, ‘isn’t that a quaint oddity,’ rather they should say, ‘never again in my country.’”

====

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act to compensate the people of Japanese ancestry who were incarcerated in World War II internment camps. The legislation offered a formal apology from the United States government and authorized payment of $20,000 (tax free) to each surviving victim.

In 1987, on year before President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, the California State Board of Education adopted, in honor of the 200th anniversary of the writing of the 1787 U.S. Constitution, the History-Social Science Framework for California Public Schools. The document has been revised often, most recently in 2016. The 2009 reposting posits the following for the eleventh grade American history course: “The relocation and internment of Japanese Americans during World War II on the grounds of national security was a governmental decision that should be analyzed as a violation of their human rights.”

“Exclusion: The Presidio’s Role in World War II Japanese American Incarceration” has been mounted at the Heritage Gallery at the Presidio Officers’ Club. It remains there for one year, leaving the former military post in March 2018.